‘Life as Art’

Exhibition reunites in death two stormy realist painters separated in life

By curating the exhibition “Life as Art: Paintings by Gregory Gillespie and Frances Cohen Gillespie,” Theodore Stebbins Jr. has brought about a reconciliation of sorts, albeit a melancholy one.

The two painters met when they were students at Cooper Union and married in 1959. They studied together in San Francisco, Florence, and Rome, and shared a devotion to the Italian and Flemish art of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Their commitment to representational art put them at odds with prevailing styles of the 1950s and ’60s – the two-dimensional abstractions of the color-field painters, the jiggy vacuity of op art, and the aesthetic iconoclasm of pop. Yet they remained true to their vision, and eventually gained recognition – Gregory in the mid-1960s, and Frances – because she had put her career on hold to raise a family – a decade later. Living in Williamsburg, and later in Amherst, the two became an integral part of the artistic and intellectual life of the area and exerted an influence on numbers of younger artists.

But with success came personal disruption. In 1977, Frances was working on a double portrait of herself and Gregory seated at a table. Gregory thought the

Life as Art:

Gregory Gillespie and

Frances Cohen Gillespie

photo gallery

composition was faulty and recommended that she saw the panel in half (both painters customarily worked on wood rather than canvas). Frances followed his advice, only later realizing its significance.

“At the time I had no idea that my marriage to Gregory would ever end,” she later wrote. “In this case, art preceded life.”

They divorced in 1983, and for a while both their careers flourished. Gregory’s large, obsessively detailed self-portraits freighted with darkly ambiguous symbolism gained increasing critical attention, while Frances’ equally meticulous flower studies in which gloxinias and chrysanthemums metamorphose into writhing, Laocoön-like presences won recognition as well.

But because of mutual hostility stemming from their breakup, neither artist would let their work be shown alongside that of the other, despite the fact that they shared similar influences, techniques, and aesthetic values. Then in 1998 Frances died of cancer. Two years later, Gregory, who was increasingly subject to bouts of despair and depression, took his own life.

The tragedy gave Stebbins, curator of American art in the University Art Museums, the opportunity to bring the work of the two artists together in one exhibition. The current show at the Fogg Museum comprises 17 works by Gregory and eight by Frances. Inevitably, the paintings bear witness to a pair of intertwined lives as much as they reflect the development of two artistic careers.

The story begins with Gregory’s paintings of the early 1960s. Two small paintings, “Roman Landscape” and “Street in Madrid,” show the artist assimilating the influence of his European predecessors. In the first, the courtyard of a dilapidated castle is populated by three female sunbathers, two nude and one in a bikini. In the second, a narrow European street rendered in the manner of a 17th century genre painting is crowded with 20th century figures including a parked car and a woman on a bicycle.

“He was trying to be a modern Flemish master,” says Stebbins. “He and Fran were aware that realism was out, but they were rebels. They deliberately put themselves outside the mainstream.”

Ten years later, Gregory had shifted to his most characteristic subject – himself. The monumental “Self-Portrait on Bed” (1973-74) shows the artist in a nearly bare room seated in a slumped, awkward posture on a mattress that looks as if it has been scavenged from a dump. Dressed in cutoff jeans, work shirt, and black sneakers without laces, Gillespie stares deep within himself. He seems devoid of will, anchored in the blank expanse of the room like the hulk of a wrecked boat resting motionless in some bleak estuary.

What life there is in the painting is relegated to its margins. On the right one can see the edge of a small landscape. In fact, it is one of Gillespie’s earlier Italian paintings. On the left, resting on a shelf, is a picture of a young, naked boy, perhaps the image of lost innocence with which the adult Gillespie is trying to reconnect. And on the windowsill, bathed in white light, is a single brown pear, full, round, and perfectly balanced, both fecund and pristine.

The images have been rendered in almost microscopic detail. The individual hairs on Gillespie’s bare arms and legs, a reddish pimple on his calf, faint blue veins on his ankle have been faithfully represented as if the artist wished to push to its utmost the ability of the painted surface to stand for reality. And yet despite Gillespie’s obvious skill, it never seems that he is simply showing off.

“His aim is always to use his gifts in the interest of the painting, not as a tour de force,” says Stebbins. “There are always emotional, psychological, and physical layers to his work. He struggled with these paintings, scraping and sanding them down, then painting them over again. Nothing came easily.”

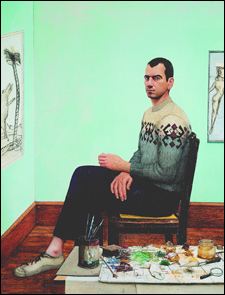

Like Rembrandt and van Gogh before him, Gillespie continued to explore his own image, often surrounding himself with strange collections of objects that both invite and resist interpretation. In “Self-Portrait in Studio, 1976-77” He sits upright in a straight-backed chair behind a table spread with the tools of his trade – brushes, paints, a palette knife, and a magnifying glass – while on either side hang, not his own paintings, but crude, cartoonlike drawings. In “Studio: Still Life, 1978,” Gillespie’s face looks through a narrow window on the left, a portrait of an androgynous-looking Frances hangs on the wall to the right, while a collection of grotesque masks, a phallic butternut squash, and an armless mannequin occupy the space between.

In his later self-portraits, these symbolic objects drop out of sight, and the artist confronts his aging form with merciless intensity. “Self-Portrait, 1995,” the first painting to greet viewers as they ascend the staircase to the museum’s second floor, shows a shirtless, graying, dissipated-looking Gillespie against a deep aquamarine background that contrasts so strongly with the orange tones of his flesh that the effect is almost assaultive. It is a frightening image, but one which, Stebbins says, does not really portray the artist as he appeared.

“Actually, these portraits don’t look anything like Greg. He was an engaging, smiling guy. He conveyed a sense of energy, of life force, which was what attracted people to him.”

Across the hall, we meet Frances in a self-portrait that is a reworking of the painting that Gregory urged her to saw in half. Arms crossed, she stares suspiciously from the corners of her eyes while a disembodied hand touches her shoulder with mollifying intent.

More characteristic of her work, however, are her flower pictures, of which there are six in the show. Just as meticulously detailed as Gregory’s paintings, but without his attention to the range of light and texture, they have a brilliantly hard, cold look. Most of them are variations on the same three elements: a vase of flowers standing in front of a mirror on a table draped with a Japanese kimono.

Using a mirror as a major compositional device allowed Frances to explore questions of reality and illusion, Stebbins says.

“You’re looking in the mirror, but you don’t see the painter, as you would in reality.”

In some cases the mirror image seems to reflect time and mortality, as in “Lydia’s Vase” (1981-82), where the chrysanthemums in the foreground are brilliant white, while their reflected images have become sear and withered. In others, like “Purple Gloxinias” (1983) and “Red Gloxinias” (1990-91) it is the mirror images that seem to conform to reality, while the “real” plants reach toward the viewer with their exaggerated leaves and petals.

Each of these large paintings, which took Frances as long as a year to complete, represent a lengthy struggle to overcome uncertainties of color, design, and composition. It is that struggle that makes them more than simple flower paintings, Stebbins says.

“You don’t read them as still life paintings. They’re not decorative. They’re more complicated, energetic. They have a sense of luxuriance and plenty, a kind of lavishness.”