It’s not just about the money

Causes of residential segregation transcend affordability

When it comes to the stubborn persistence of residential segregation in metropolitan Boston, it’s not just the economy, stupid.

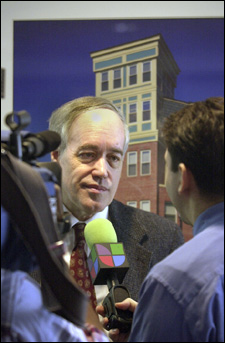

New research from the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University shows that in a region where median home prices now exceed $400,000, affordability alone does not explain the continued patterns of racial segregation that exist in the Boston area. At a conference Friday (Jan. 23) called “Toward Residential Choice in Segregated Metro Boston,” researchers presented findings that implicated a complex tangle of factors, including housing preferences and discrimination. The conference, at the offices of MassHousing in downtown Boston, was sponsored by the Civil Rights Project (CRP) with the Greater Boston Civil Rights Coalition and Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association.

“In metro Boston today, segregation is due to much more than money,” said CRP researcher Nancy McArdle, noting that well-off blacks and Hispanics are as segregated from their white counterparts with similar incomes as poor blacks and Hispanics are from poor white households. Boston is the nation’s third whitest large metropolitan area.

McArdle summarized a report, co-authored with David Harris of the Fair Housing Center of Greater Boston, which modeled the spatial distribution of homeowners by race across the metropolitan area (defined as Bristol, Essex, Middlesex, Norfolk, Suffolk, Plymouth, and Worcester counties) as if the value of their homes were the only factor in determining where they live, what the researchers call “colorblind” analyses.

The researchers found that African-American and Latino homebuyers were greatly overrepresented in some areas – Lawrence, Chelsea, Lynn, Everett, and Revere for Latinos; Randolph, Brockton, Boston, and Milton for African Americans – even after accounting for affordability.

“The flip side is that in most places, they’re very underrepresented,” said McArdle. In 80 percent of cities and towns in metro Boston, she reported the number of black and Latino homebuyers was less than half what would be predicted based on affordability alone.

“Is it preferences or is it overt discrimination or is it something else?” she asked.

Discrimination still at work

Discrimination – what he called “the D word” – is certainly a player in the segregation game, said Harris. He detailed results of an ongoing audit of Realtor practices conducted by the Fair Housing Center.

The audit sent “testers” – white and African-American and white and Latino would-be homebuyers – into Realtors’ offices in a variety of metropolitan Boston communities. The pairs of testers were equally matched in every way but one: To up the ante in determining whether discrimination exists among Realtors, the black and Latino testers – what Harris called the “protected testers” – brought stronger financial qualifications to their real estate searches.

“The results are, in a word, sobering,” said Harris. “In 17 out of 17 cases, we found differences in the treatment that the protected-class testers received versus the white ones.”

Unlike the white testers, African Americans and Latinos were regularly required to be preapproved for mortgages (rather than simply prequalified), were quizzed about their careers, and were steered away from certain communities. Realtors

were more likely to suggest that blacks and Latinos visit open houses rather than see homes on appointment with the Realtor, and shared less informal advice and information with the home-seekers of color.

While this discrimination is more subtle than overt, in the region’s competitive real estate market “these are devastating differences that make the difference between success and failure in obtaining a house,” said Harris.

Such discrimination exists among lenders, too, found Jim Campen of the Gastón Institute at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

“Mortgage lending in Boston is in general operating to reproduce the region’s highly segregated residential patterns,” he said. “When blacks and Latinos apply for home purchase mortgage loans, they are more than twice as likely to be denied as whites.” Further, disparities in denial rates rise as income rises, and blacks and Latinos refinancing homes were far more likely to receive loans from subprime lenders, with their attendant higher rates and fees, than whites.

“The disparities in mortgage lending play a major role not only in who lives where, but also in denying many people of color access to home ownership that has been a major source of wealth accumulation for white Americans,” said Campen.

Who wants integrated neighborhoods?

Tara Jackson, senior research director at International Communications Research, explored housing preferences, the third leg of the segregation stool. Could it be that the region remains segregated because people of color simply choose to live among other people of color? The answer, she found, is as complex as the results of her colleagues’ research.

“There is widespread support for integration in Greater Boston,” Jackson reported, although it varies somewhat by race. Blacks and Latinos overwhelmingly support a neighborhood that is 50 percent minority and 50 percent white; majority white neighborhoods are the least preferred neighborhoods to blacks and Hispanics.

“Whites generally support integration across the board,” said Jackson. “But at the same time, another pattern that we see developing is that, with regards to blacks, whites are most supportive of black integration in its earliest phases, when there’s just one black family moving into the neighborhood.” As racial integration approaches the 50-50 ratio preferred by blacks and Latinos, whites’ tolerance for integration diminishes.

A second panel in the fast-paced conference presented the policy recommendations of several housing experts, including Kennedy School of Government associate professor Xavier de Souza Briggs. A former housing policy expert in the Clinton administration, he set Boston’s residential segregation in a national context.

As diversity is on the rise nationally, he said, discrimination persists but is going underground, where it’s more subtle and harder to police. And the preferences for integration Jackson discussed are increasingly difficult to satisfy. “Most Americans like some integration, but not too much,” he said.

Civil Rights Project co-director and Professor of Education Gary Orfield, who moderated the conference, applauded the multidisciplinary findings for debunking commonly held myths about the forces behind segregation. “The market isn’t working freely like people think,” he said.

In our increasingly diverse society, he said, integration is important to avoid ghettoization of any racial group. “We’ve never had separate but equal in American history,” said Orfield. “Integration is a very positive experience. When you do this the right way, it has very positive benefits for everyone.”