From vellum to pixels

David Remington offers expertise in project to digitize Codex Sinaiticus

The Codex Sinaiticus is the earliest manuscript of the complete New Testament and the earliest and best witness, according to Bible scholars, for several books of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament). Dating from the middle of the fourth century, the manuscript was originally written by hand on vellum (calfskin or sheepskin). Now, having endured into the 21st century, it will soon be replicated in pixels. Four institutions currently hold leaves from the Codex – the British Library, Leipzig University Library in Germany, National Library of Russia, and St. Catherine’s Monastery in Egypt – and they have come together to create a digital reunification of the Codex Sinaiticus that will be published and placed on CD-ROM.

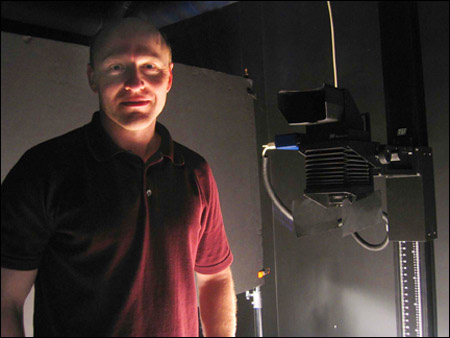

David Remington, collections reformatting photographer in the Digital Imaging and Photography Group in Widener Library, is serving on the Codex Sinaiticus Technical Standards Working Party, composed of representatives from each institution and digital imaging specialists. The international team’s goal is to create a scholarly edition of the Codex and as exact a replication as possible.

A few of the manuscript’s leaves were initially discovered in 1844 by German scholar Constantine Tischendorf at the monastery of St. Catherine at Mt. Sinai, Egypt. Tischendorf realized the manuscript’s significance and asked the monks if they had additional leaves, but the monks were reluctant to show him more of the document. A few years later, Tischendorf returned under the patronage of the Russian Czar Alexander II and persuaded the monks to reveal what is now known as the earliest complete manuscript of the New Testament. Tischendorf secured the Codex for the Czar. In 1917, with the revolution, the Codex changed hands once again.

In 1933, the Soviet Union sold the manuscript to the British Library. Today, the remaining 400 leaves are divided among the four institutions (British Library, Leipzig University Library, National Library of Russia, and St. Catherine’s Monastery), each successive “owner” (the monks, Tischendorf, the Russians, etc.) having retained a bit of the manuscript as it passed from hand to hand over the years.

The institutions are now working together to digitally reunite the manuscript. An expert in exacting digital reproduction, Remington was asked to serve as an outside consultant on the project. In July, representatives from three of the four institutions met for the first time at the British Library, where the majority of the manuscript is currently held. Remington was asked to compile a list of recommended technical specifications for the project, such as the type of camera needed, and appropriate lighting, lenses, file format, method of archiving the project’s digital assets, and the image capture process.

“The material is challenging and the project calls for the highest-quality reproduction. We are consulting with conservators and curators on issues specific to this manuscript, for instance a lot of the text is faded and there are faint notations along the borders, between passages and in the gutter. Some of the pages have been mended or have tiny punctures used for aligning the columns. All of this detail is relevant to scholarly study and must be available in the reproduction. These considerations inform our choices for capture resolution, lens, necessary depth of field, style of lighting, and type of backing material,” said Remington. “It is important that all technical aspects of the digital capture and image processing be given careful consideration. We are employing a color-managed work flow – a process that is used to maintain exacting color reproduction from capture, to print, to distribution on the Web.”

The Technical Standards Working Party is collaborating with a Conservation Working Party, composed of conservators from the British Library, Leipzig University, and St. Catherine’s Monastery, and other independent experts. The conservation group will make recommendations on how the leaves should be handled and on possible pre-imaging treatments. Each institution will perform its own digital photography, in part because transferring the leaves from one climate to another, such as from Egypt to England, could damage them.

In October, Remington presented his recommendations to the other members of the Technical Standards Working Party, who used the information to draft a proposal for the technical process of reproducing the Codex. An oversight committee is currently reviewing the proposal. The digitization of the Codex should begin in summer or fall 2004. Remington will continue as consultant as the project moves forward.

“David’s technical skills, and his subtle eye for color fidelity and image quality are exceptional, making him a central and authoritative resource among the photographers in our group, among other colleagues at Harvard, and now, increasingly, within a growing network of colleagues at other institutions,” said Bill Comstock, manager of the Digital Imaging and Photograph Group.