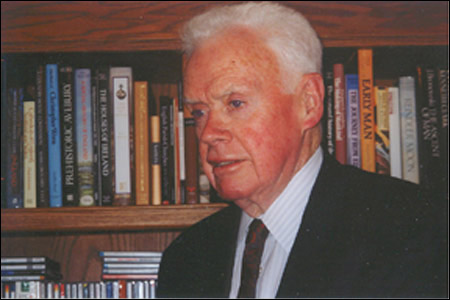

Expert on ‘all things Irish,’ Kelleher, dies at 87

John V. Kelleher, professor of Irish studies emeritus in the Department of Celtic Languages and Literatures, died Jan. 1 at Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis after a brief illness. He was 87.

Kelleher was born in Lawrence, Mass., on March 8, 1916. Lawrence, known as the “Immigrant City,” was the classic melting pot, full of people close to their ethnic roots (51 nationalities, speaking 45 different languages, in the 1910 census) and looking forward to a new life in America.

Kelleher’s family looked back into Ireland as well, and he absorbed all things Irish from childhood on. He began learning to speak Irish when very young from his grandmother, who, like all his grandparents, had come from Ireland in the mid-1800s. He continued lessons with his grandfather’s cousin, Augustinian priest Daniel J. O’Mahony.

In the last few years, Kelleher’s granddaughter, Margaret McCauley ’95, and her husband, Suresh Chanmugam ’95, brought this full circle and were practicing their Irish on him.

Graduating from high school in the depths of the Depression, Kelleher saved money for college by working with his father and uncles for two years as a carpenter and roofer, and serving in the National Guard. At Dartmouth, he read “every book of Irish interest in Baker Library” and as a senior fellow had a year of independent study to pursue his “great plan for learning everything about Ireland.” He received his A.B. with honors in English in 1939.

Kelleher came to Harvard in 1940 as a junior fellow in the Society of Fellows, and continued his plan and studies in the Harvard libraries and with Kenneth Jackson, an authority on ancient British languages. It was while he was a Junior Fellow that he met Henry L. Shattuck, a prominent Boston lawyer and treasurer of Harvard College, who became perhaps his greatest friend, and it was as a Junior Fellow, too, that he delivered the Lowell Lectures, on modern Irish literature, at age 26.

Kelleher was a great admirer of President Lowell and his plan for the Society of Fellows as an alternative to Ph.D. programs for students for whom there really was no pre-existing field and therefore no one to study under. Lowell, who accomplished many things in his 24 years as Harvard’s president, including introduction of the House System, was most proud of the Society of Fellows: The 24 “most brilliant young men that can be found, with the guidance and companionship of professors who have achieved eminence.” True to Lowell’s vision, Kelleher’s highest earned degree was his A.B., and he is regarded as the founder of his field, Irish studies.

During World War II, Kelleher served in military intelligence at the Pentagon, assigned to the Korea Desk.

After the war, he visited Ireland for the first time in 1946, sending home long illustrated letters almost daily as he cycled his way around the country. For the rest of his life he remembered every event and interaction of the trip. When he rode into Fermoy, he recognized the scenes of his grandmother’s youth as she had described them to him – before her death when he was 6. In Macroom, seat of the Kellehers, he asked about his own branch, and was told, “there’s a frightful power of Kellehers here, and none of them ever amounted to anything.”

During this trip he met and befriended many of the writers, artists, and intellectuals of the day, and was particularly close to Sean O’Faolain and Michael O’Donovan (Frank O’Connor).

In 1947, he began his long teaching career in Irish history and literature. Kelleher was a serious and exacting teacher, but over the years many of his students became his friends for life. In 1960, he became professor of modern Irish history and literature, a chair endowed by Shattuck. He was a voting member of the departments of English and History. Kelleher also taught highly popular Extension School courses every year for nearly three decades: Yeats and Joyce, modern Irish literature, and both modern and medieval Irish history. During the course of his career he was awarded an honorary M.A. by Harvard (1953) and honorary Litt.D.s by Trinity College, Dublin (1965) and the National University of Ireland, Cork (1999).

Kelleher’s colleagues remember him for the extraordinary range of interest he displayed in all things Irish, for his phenomenal memory, for his genial humor, and for his gracious, considerate, often self-deprecating manner.

“He was a phenomenal man,” said Gene Haley, lecturer on Celtic languages and literatures. “His range was incredible. He was a leading expert in history and literature, with a real sensitivity for the nuances and human factors of his subject.”

As a historian, Haley said, Kelleher had “a skeptical, unromantic attitude toward his sources and a work ethic few could boast of. His wide, deep, analytical mastery of the early Irish annals, for example, could only have been attained by a slow, steady progress through a wilderness of details and conflicting claims.”

But in addition to being a rigorous scholar, Kelleher was also a poet and translator with “a wisdom concerning human nature and a sensitivity to fine-tunings of the language (Irish or English) that made him a brother-artist to the modern Irish poets, novelists, short story writers, and dramatists he studied and explicated,” said Haley.

Helen Vendler, the A. Kingsley Porter University Professor, recalled Kelleher’s kindness and encouragement when she was a young graduate student in Harvard’s Department of English and American Literature and Language.

“It was rare at that time for a professor to encourage women graduate students as much as men, but he made no distinctions according to gender,” she said.

His tact and sensitivity could be seen in the comment he made on a paper Vendler wrote for his course in modern Irish prose in which she had failed to recognize the irony in a short story by Frank O’Connor. Instead of saying something biting or condescending, he had merely written, “Suppose you look at it this way …?”

Vendler said she was often astounded by Kelleher’s knowledge and understanding of modern Irish literature. He appeared to know all of William Butler Yeats’ poetry by heart, she said, and “knew more about Joyce than anyone else. He had doped out most of ‘Finnegan’s Wake’ before anyone else understood it.”

Although he spoke with a stammer, Kelleher was able to lecture and read aloud without impediment, and his deep, finely modulated voice could bring out meanings in a poem through nuance alone.

“If you heard him read a poem that you didn’t understand, you would suddenly understand it, and the understanding would be somehow transfused into you by his intonation,” Vendler said.

Director of Admissions Marlyn McGrath Lewis, who wrote her Ph.D. dissertation in Celtic studies under Kelleher’s supervision, remembered the democratic basis on which he treated graduate students despite their comparative deficiencies in knowledge and experience.

“You felt John treated you as if you were a colleague. If you signed on to the team, you had the key to his office, you could use his books, and you could use his ideas,” she said.

In addition to teaching in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Kelleher served Harvard in other ways. He was a faculty associate of Lowell House, and he also served on the College’s Standing Committee on Admission and Financial Aid from 1963 to 1975.

“He never forgot that admissions was about people and that each applicant represented a story, often several stories, which deserved careful consideration and respect,” said Lewis. “He often rooted for the underdog – the student who had overcome disadvantages to position himself for higher education, and who wasn’t afraid to dream of an elite place like Harvard. His comments were always discerning and appreciative – and often pithy. Old-timers in the Admissions Office recall his brief summary of one folder where he seemed to get right to its essence: ‘this student is exceptionally well-rounded. But the radius is very narrow.’”

Zeph Stewart, master of Lowell House emeritus, said that Kelleher “had a sure eye for pomposity or self-importance in others, and he was quick to deflate them with quiet wit and humor, never aggressively or meanly. John was a constant support throughout those years, and our friendship continued after his retirement. He was a man of unshakeable (but never blind) loyalties. He was someone whom one was proud to have as a friend.”

Kelleher retired in 1986. In 1991, he and his wife, the late Helen C. Kelleher, moved to St. Louis. Following her death he continued to live in St. Louis, near three of his four daughters, and to encourage academic departments that were developing Irish studies programs. He donated thousands of scholarly books from his own collection to libraries at both the University of Missouri, St. Louis, and Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. He enjoyed excellent health, which he credited to his lifelong habit of long daily walks, averaging three miles a day. His legendary mental acuity was intact to his last day.

He is survived by four daughters: Brigid McCauley ’64, Peggy Oates, and Nora Stuhl, all of St. Louis, and Anne Fisher of North Attleboro; two sisters, Barbara Slack and Dorothea Buckley, both of Richmond, Va.; and eight grandchildren.

Visiting Harvard last November, Kelleher was told that the Celtic Department had begun raising funds for an annual lecture to honor his outstanding contributions to Irish studies. Donations to the fund will help make the lecture series a fitting and lasting memorial to its namesake, a veritable giant in so many aspects of Irish studies.

Donations may be made to The Kelleher Lecture, c/o Dept. of Celtic Languages and Literatures, Barker Center, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138.