Depressed get a lift from MRI

Brain scanners please manic-depressives

Both the patients and psychiatrists were startled. Manic-depressives undergoing brain scans, not a really pleasant experience, came out of the machine happier than when they went in.

One severely depressed woman left the scanner laughing and joking. It was totally not like her. After a 20-minute scan, another woman happily asked a researcher, “What did you do to me?”

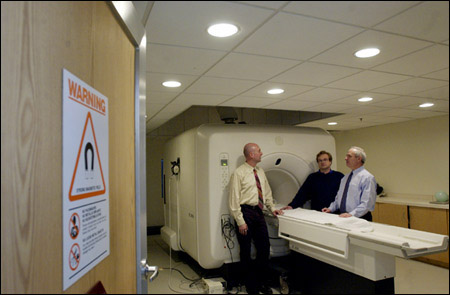

Aimee Parow, the researcher, told Perry Renshaw, director of the Brain Imaging Center at McLean Hospital, a psychiatric affiliate of Harvard Medical School, where the scanning was done. The research team was trying to determine how the brain chemistry of manic-depressives differs from that of people who are free of the problem. Nobody expected to find such a happy result. “It was amazing,” Renshaw comments.

He described what happened to Bruce Cohen, president and chief psychiatrist at McLean. “I was excited but skeptical,” he recalls. “One part of me said, ‘It’s unlikely.’ But another part said, ‘Why not?’ People go in and out of depression on their own. Electromagnetic fields generated by the scanner could nudge a depressed brain back toward normal.”

It was decided to investigate the surprise further. Under the direction of Michael Rohan, an imaging specialist, 30 people undergoing treatment for manic depression, known as bipolar disorder, were selected for a scanning experiment.

To make sure it was the electromagnetic fields generated by the scanner that were lifting spirits and not other aspects of patient treatment, 10 other patients underwent sham scans for comparison. Finally, to take into account the placebo effect, 14 healthy people were scanned. (The placebo effect causes people to feel better just because they are getting medical attention.)

Twenty-three people with bipolar depression (77 percent) felt better after scanning than before it. Only three (30 percent) of those who received sham scans said they felt better. Four of the healthy comparisons (29 percent) reported that the scans elevated their moods.

Mood improvement

“It’s a small and preliminary study based on an accidental discovery,” admits Cohen, who is also a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “But our results suggest that the electric fields produced by certain types of brain scans are associated with mood improvement in people with bipolar disorder.”

“We were surprised at our good fortune in discovering this effect, and we are excited about the initial findings,” adds Rohan.

The next step is do a larger study to answer such questions as how long the effect lasts, and how such scans make bipolar people happy.

When asked how long the effects of the happy machine lasted, some people said hours, others, days. One woman said she felt better for a week. Cohen says he hopes that a study that yields more definitive results can begin as early as next month. Such experiments should separate the effect of anti-depressant drugs taken by some of the subjects.

The researchers are intrigued by the fact that all of the manic-depressives not on medication responded favorably, as opposed to two-thirds of those taking drugs. Cohen doesn’t know why, but he speculates that “medication may reduce the sensitivity of brain cells to the electromagnetic fields. If that turns out to be so, we may be able to raise the intensity of the fields.”

The type of scan used is known as Echo-Planer Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging, or EP-MRSI. It uses low-intensity magnetic fields to produce three-dimensional images of the brain’s chemistry, which reveal various abnormalities in its nerve-cell activity. The specific timing and amplitude of the magnetic pulses induce electric fields that may match the natural electrical firing rhythm of brain cells, Rohan and Cohen speculate.

“The pulses travel from right to left trough a thick cable of nerves that coordinate activity between the two halves of the brain,” Cohen explains. The two halves perform different tasks; for example, the right hemisphere is considered more involved in spatial processes like map reading, while the left is more dedicated to logic and language in many people. “In depression, the two halves of the brain may get out of balance, and the electromagnetic pulses may restore the balance,” Cohen says.

Head hits of happiness

Researchers at Harvard Medical School and elsewhere are experimenting with another technique that uses electromagnetic pulses to treat depression. Called transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, it involves holding a figure-of-eight-shaped wand near a person’s head. Two coils of wire on the wand generate a strong magnetic field that induces electric currents in brain cells.

“We believe that TMS works by normalizing disturbed levels of brain activity,” says Alvaro Pascual-Leone, an associate professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School. In experiments at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, he and his colleagues lifted the spirits of depressed patients who are resistant to anti-depressant drugs.

“TMS uses electric fields that are more localized and much stronger than EP-MRSI,” Cohen notes. “Some patients have reported feeling discomfort and there is a some danger of causing seizures with TMS that does not occur with our system. However, it may be that the two methods use different techniques to achieve the same result.”

Neither scanners nor wands are ready for general use yet. If more experiments show widespread effectiveness at relieving depression, the electric fields may be better medicine than drugs. Anti-depressants can have disturbing side effects, including fatigue, anxiety, loss of libido, and increased blood pressure. They usually take weeks to work, and sometimes they don’t work at all. So far, the scanning technique seems free of the side effects of drugs and TMS.

However, brain scanners that fill a large room and cost a million dollars or two are not a very practical alternative. McLean researchers have begun working on the design of a smaller, much cheaper device. “We plan to test a tabletop scanner in a study of a larger number of patients,” Rohan says. Someday, he speculates, patients may be able to get their depression eased during a 20-minute nap at a doctor’s office.

Those not suffering depression received as little benefit from scanning as those who underwent a sham treatment, ruling out the possibility of getting a quick hit of happiness at your doctor’s office to brighten up a bad day or prepare for a dreaded meeting.