Film, panel examine bioethics

What happens when genetic technology collides with the court system

It’s like some brain-teasing riddle – How can a baby have five parents, none of whom are recognized by law?

But the riddle took on very real life when Luanne and John Buzzanca, a married couple who had been through the expense and heartbreak of unsuccessful fertility treatment, finally gave up hope of having a baby who shared their DNA and instead obtained eggs and sperm from anonymous donors and hired a surrogate mother to gestate the fetus.

All went well until the eighth month, when John Buzzanca sued for divorce and claimed that since he had no biological connection to the child, he also had no responsibility as its father. The judge essentially agreed and ruled that the child had no legal parents.

A court of appeals later overturned his decision, ruling that since it was the Buzzancas’ intention that caused the baby to be born, they were its legal parents. That decision has since been cited in courts around the world, which have faced cases similar to the Buzzancas’ with increasing frequency.

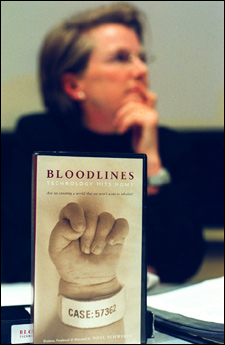

The Buzzanca case is one of the stories told in a documentary film, “Bloodlines: Technology Hits Home. Are We Creating a World That We Won’t Want to Inhabit?” The film – written, produced, and directed by Noel Schwerin – premiered on PBS this past June. On Dec. 2, it was shown as part of a forum sponsored by the Harvard Medical School’s Division of Medical Ethics at Harvard Medical School (HMS).

Schwerin was one of four panelists who spoke about the film and the questions it raises. The others were Judy Foreman, a nationally syndicated health columnist and lecturer at HMS; Eric Kupferberg, assistant director of public programs at the Division of Medical Ethics; and Daniel Callahan, HMS senior fellow.

“In the film, I was trying to make sense of reproductive and genetic technology and the collision of technology and the courts. These are great stories, the human stakes are high, and they make us care about what happens,” Schwerin said.

The film’s other stories were equally compelling and thought provoking:

n a lesbian couple who successfully petitioned the courts to have both partners declared legal parents of the three children to whom one partner had given birth;

n a surrogate mother, pregnant with twins, who was told by the couple who hired her that since they were divorcing they no longer wanted the babies;

n a developmental biologist who seeks to patent a creature grown from the combined cells of a human and a chimpanzee, a process that is entirely feasible given today’s technology (the creature does not yet exist, and the biologist’s intention is to pursue a test case with the aim of making such experiments illegal);

n a severely disabled victim of Parkinson’s disease who made a remarkable recovery after undergoing an experimental treatment in which fetal pig cells were injected into his brain.

Kupferberg, who also holds an appointment as lecturer in the Science, Technology, and Society Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.), was the main speaker in a program following the showing of the film. He spoke passionately about the need for a new model for bringing scientific discoveries to the attention of the public, one that acknowledged the active involvement and responsibility of science journalists and their audience while questioning the presumed insularity and objectivity of scientists.

He elaborated on this theme with a PowerPoint presentation in which he deconstructed some of the imagery and language employed in the film in order to uncover deeper meanings and ask more probing questions. By such an approach, he hoped to “construct a dialogue” that focuses on questions of biomedical ethics, one that would bring into play the political as well as the ethical dimension of these complex issues.

“This dialogue is not something that we can fix in a moment,” he said. “It’s going to be an ongoing negotiation. We’re going to be in this for the long haul. We’ve got to be willing to talk and keep talking.”