Diplomacy of Lewis and Clark stressed in exhibit

Native American artifacts on show

In 1803, when Americans spoke about going west, they meant Ohio, Kentucky, or Tennessee. The phrase “manifest destiny” – the God-given right of Americans to spread over the continent – wouldn’t be coined for another four decades. America didn’t extend from “sea to shining sea” – rather it shaded off on its western edge into a stupendous and perilous unknown.

So when Thomas Jefferson purchased from France an enormous tract of land known as Louisiana, he was essentially buying real estate sight unseen. The first order of business after papers were passed was to send out some reliable scouts to inspect the property.

The men Jefferson chose were Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. On May 22, 1804, they set out from St. Louis on the Missouri River with a team known as the Corps of Northwest Discovery. They went in search of a water passage that they hoped would link the East Coast with the Pacific Ocean.

They also mapped the terrain through which they traveled and collected plant, animal, and mineral specimens. According to Jefferson’s instructions, they were to treat the Indians they encountered “in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit” and to encourage them to come to Washington, D.C., to meet their “Great Father.”

It is this diplomatic aspect of the Lewis and Clark expedition that is emphasized in the bicentennial exhibition opening this evening (Dec. 11) with a special reception at the Peabody Museum.

“From Nation to Nation: Examining Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection,” curated by Irene Castle McLaughlin, associate curator of North American Ethnography, brings together nearly 60 items from the period, some of which have been

A special exhibition opening and reception will take place today (Dec. 11) from 5 to 8 p.m. Family Day will be from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday (Dec. 13). The exhibition will be on view until Dec. 31, 2005. The Peabody Museum is located at 11 Divinity Ave. For more information, call (617) 496-1027.

painstakingly identified as objects actually acquired by Lewis and Clark in ritual exchanges with various Native American tribes.

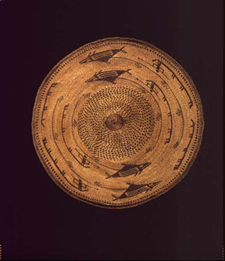

As they traveled westward, Lewis and Clark exchanged clothing, American flags, tools, and silver “peace and friendship medals” for peace pipes, beaded bags, feathered headdresses, and decorated buffalo robes. The exhibition highlights their mission to initiate diplomatic relations with western tribes to secure their allegiance and wrest the Indian trade from America’s international rivals.

Most of the objects Lewis and Clark sent back eventually ended up in Charles Wilson Peale’s museum in Philadelphia. When Peale’s descendents closed the museum in 1850, the majority of its ethnographic collection was sold to museums belonging to P.T. Barnum and Moses Kimball, both of which were destroyed by fire about 50 years later. At this point, the surviving objects were transferred to Harvard’s Peabody Museum.

In 1997, Peabody Museum director Rubie Watson asked McLaughlin to begin an in-depth examination of the collection, the first undertaken since the museum acquired the objects in 1899. McLaughlin and a team of anthropologists, art historians, and material culture specialists have meticulously examined the collection, combing through existing documentation as well as scrutinizing the objects themselves.

An account of this investigation and of the stories told by these historically significant and eloquent artifacts is lavishly presented in McLaughlin’s book “Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis and Clark’s Indian Collection” (Peabody Museum, University of Washington Press, 2003).