Three from University among MacArthur Fellows

Instructor Nawal Nour and Assistant Professors Jim Yong Kim and Xiaowei Zhuang awarded prestigious grant

Three Harvard faculty members are among this year’s 24 MacArthur Fellows, which the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation announced Sunday (Oct. 5). Each is a recipient of the fellowship’s $500,000 “no strings attached” grant.

They are Jim Yong Kim, assistant professor of medical anthropology in the Department of Social Medicine and assistant professor of medicine at the Medical School (currently on leave); Nawal Nour, also at the Medical School, an instructor in obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology; and Xiaowei Zhuang, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

President Lawrence H. Summers commented, “These three well-deserved awards recognize the extraordinary achievements of individuals within our community. The awardees deserve our congratulations and their work earns our admiration.”

Jim Yong Kim: ‘It’s a huge responsibility’

“I was incredulous when they told me I had won,” Jim Yong Kim says of his MacArthur award. “I told Dan Scololow (director of the Mac Arthur Fellows Program), “I’m not one of those people who gets this award.”

Kim’s next thought was how to spend it. “It’s a huge responsibility,” he comments. “It would be difficult to keep much for myself. I want to find a way to accelerate what I’ve been doing for the past 15-20 years, helping the poor get access to better health care. Perhaps I can do something really significant. I feel a deep sense of responsibility to do so.”

Kim, 43, is on leave from the Harvard Medical School to serve as adviser to the director general of the World Health Organization (WHO). He will be part of an ambitious program that he calls the largest public health project in history. The WHO is working with doctors in developing nations to get 3 million poor people infected with HIV-AIDS into treatment by 2005. That will increase by 10 times the number of HIV-AIDS patients in these countries who currently receive treatment.

The WHO project involves the kind of effort that won Kim his MacArthur Fellowship. Four years ago, developing tuberculosis that is resistant to common drugs was a death sentence for the poor. The high cost of treating the rapidly growing drug-resistant form of the disease was making it impossible for them to survive. Working with Paul Farmer, a former MacArthur winner at Harvard Medical School, Kim co-founded the nonprofit Partners in Health Care. That organization devised a plan that successfully cut the cost of treating multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among the poor by 95 percent.

“We found a mechanism to lower the price of these expensive drugs,” Kim notes. The mechanism involved getting governments and nonprofit groups to cooperate in negotiating lower prices. At the same time, Partners in Health assured effective administration of the drugs through local doctors and community supervision. The plan produced a dramatic rise in successful treatment of patients in places like Russian prisons and Peruvian ghettos.

Kim’s vision “inspired local communities, world health organizations, political leaders, and pharmaceutical companies to collaborate productively,” according to the MacArthur Foundation. “It was personally satisfying to participate in a program that converts death sentences into affordable treatments,” Kim comments. “I want to do the same thing as a MacArthur Fellow.”

Kim received his M.D. from Harvard Medical School in 1991, and a Ph.D. in anthropology from Harvard University in 1993. He was named co-director of Harvard’s Program in Infectious Disease and Social Changes in 1996. Recently, he was named chief of the newly established Division of Social Medicine and Health Inequalities at the Medical School.

– By William J. Cromie

Nawal Nour: ‘Absolutely stunned’

Nawal Nour, 37, a Harvard-trained obstetrician and gynecologist and an instructor in obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, is the founder and director of the African Women’s Health Practice at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The clinic, the only one of its kind in the United States, addresses the unique medical and emotional needs of African women who have been genitally circumcised.

Born in Sudan to a Sudanese father and an American mother, Nour grew up bilingual in English and Arabic. While doing her ob-gyn residency at Brigham and Women’s, she found herself treating a growing number of African women who had heard about her through word of mouth.

“Having grown up in Sudan and Egypt, female circumcision wasn’t shocking to me,” she said. Her familiarity with the practice allowed her to relate to her patients sympathetically and to build a relationship of trust.

In training health providers to treat circumcised women, Nour urges them to investigate the process beforehand and deal with the feelings of revulsion and outrage it may provoke.

“During a pelvic examination, which can be humiliating in itself, is not the time for a health provider to freak out and say, ‘Oh my God, what happened, who did this to you?’ Most of these women don’t feel they are victims. It’s something that has happened to their mothers, their aunts, their sisters. And if a health provider makes them feel uncomfortable, they probably won’t come back.”

Nour’s work moves beyond the cultural debate regarding female circumcision to recognize that it also represents a chronic and lifelong medical risk. She addresses these issues through treatment (including reconstructive surgery), community outreach, and education of health professionals. At the same time, she tries to raise awareness in her patients of the negative impact of female circumcision in an effort to prevent the practice from being perpetuated in the next generation.

Nour, who was delivering a baby when she heard that she had won the award, said that she was “absolutely stunned. I actually got heart palpitations from sheer delight.”

Her goal now is to set up health centers in Africa modeled on the practice she has developed here.

According to Joseph Martin, dean of the School, “Both Nour and Jim Yong Kim have incredible track records for developing innovative programs for helping people who have slipped through the significant gaps in society’s safety nets.

“The Harvard Medical School community has been proud of what Jim and Nawal have already accomplished and looks forward to what they can do with the assistance of the MacArthur Foundation.”

– By Ken Gewertz

Xiaowei Zhuang: Surprised

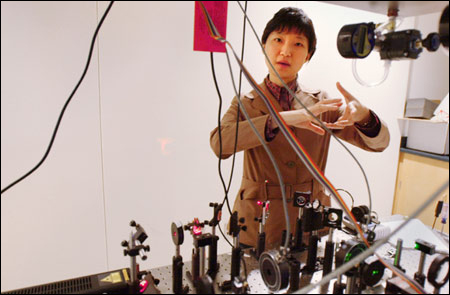

Xiaowei Zhuang, 31, an assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology who has done pioneering research in the study of individual molecules, has been named a 2004 MacArthur Fellow.

Zhuang, who also has an appointment as an assistant professor of physics, was trained as a physicist before switching to biophysics. Zhuang has recently begun to apply the methods used on individual molecules to the study of viruses and their behavior.

Most research in these same fields has focused on how masses of molecules or viruses behave. While such an approach can lead to valuable insights, it also fails to detect the individual variations that can provide important clues to how individual units function, Zhuang said.

Large biological molecules, such as proteins and RNA, are folded into complex shapes that affect how the molecule functions.

Zhuang has studied how the RNA molecule folds itself into its final shape, discovering that identical RNA molecules sometimes take different paths to the same end point. Her more recent studies of viruses have illustrated, step-by-step, the paths viruses take to infect cells.

“It allowed us to see a single virus particle inside a cell. We can follow it in real time and see each and every step in the pathway,” Zhuang said. “I think it has a very bright future [as a way of revealing] the infection mechanism.”

Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) Dean William C. Kirby said FAS is proud of Zhuang’s work and he is gratified that the MacArthur Foundation also recognized it.

“Xiaowei Zhuang’s path through condensed matter physics and chemical/physical biology is as compelling as the paths of the individual molecules she studies for their clues to biological processes and the potential insights they offer into therapeutic treatment of infectious diseases,” Kirby said. “She practices science with a remarkable versatility and originality. We are so proud of her achievements, and we are gratified that the MacArthur Foundation has recognized her talents.”

The MacArthur fellowships, also called “genius grants,” are awarded out of the blue by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The grants come with no strings attached – no projects required, no reports due – to promising people whose endeavors span a broad range of fields, from art to science.

The foundation’s philosophy in awarding the grant is to target original, creative people, give them “the gift of time” to pursue their work, and then, essentially, get out of the way.

Zhuang said when the foundation called her on Tuesday (Sept. 30) and began explaining how the fellowship works, she at first thought they wanted her to join their nomination panel. It was only after a few minutes that she realized she had won the fellowship, along with its $500,000 grant.

Zhuang said she was pleasantly surprised at the news of the fellowship. She said she hadn’t decided how to use the grant money, but said she might use it for exploratory research that would be difficult to fund otherwise.

Zhuang began her research in another field entirely. She received a bachelor of science from the University of Science and Technology of China, and both a master of science and a doctorate from the University of California at Berkeley, all in physics.

Her early work, on liquid crystals, showed that liquid crystal behavior was determined by the behavior of crystals at the boundary layer with a treated substrate such as a computer screen. Her findings have potential applications in improving the resolution of the liquid crystal displays in use today as computer screens.

It wasn’t until her postdoctoral work began in 1997 at Stanford University that she began working on biological molecules. Zhuang credited collaborations with several other research groups and said that a number of her new findings wouldn’t have been possible without active participation of these groups.

Zhuang said she believes her work, in addition to increasing the understanding of how molecules and viruses behave, will be useful in drug discovery. By being able to see the individual steps of viral entry, for example, drugs can be targeted to interfere with specific stages of the process.

“Being able to see at that level is very important,” Zhuang said.

– By Alvin Powell

This year’s MacArthur Fellows run the intellectual and creative gamut from biochemistry to blacksmithing. They are selected by anonymous nomination – there is no application or interview process – and they receive $500,000 over five years to use as they see fit.