President Summers becomes principal for a day

Takes principal role at Allston’s Jackson Mann School

There were two principals walking the halls of Jackson/Mann Elementary School last Tuesday (Oct. 28) – one who has helped to shape the school and its children over the past 12 years, and the other, a newcomer, who runs a school across the Charles River that those children may one day attend.

Photo gallery:

Principal for a day

“Hi, my name is LARRY, and I’m the principal of a very big school that starts with the letter H. Does anyone know what school I’m from?” President Lawrence H. Summers said to a group of 5- and 6-year-olds, his voice booming above the chatter of a nearby class. “Harvard,” blurted a young girl, a step ahead of her classmates still contemplating the question.

It was Summers first visit to the Jackson/Mann Elementary School in Allston and his first-ever turn filling the shoes of an elementary school principal. Summers was one of 57 Boston CEOs, heads of nonprofits, hospitals, and government, who left their board rooms and conference rooms to take the reins of a Boston public school for half a day. Organized by the Boston Plan for Excellence, in coordination with the office of the mayor and the superintendent of public schools, “Principal for a Day!” afforded Hub leaders a chance to learn firsthand about changes in instruction and challenges Boston’s urban schools face, and to share ideas and insights with the teachers who are helping shape the next generation.

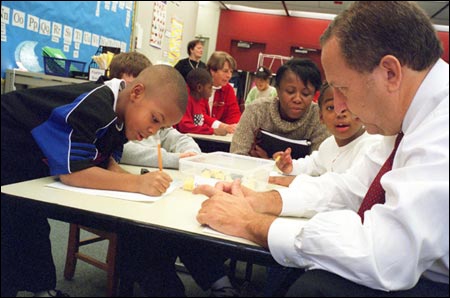

From 8 a.m. to noon, Summers accompanied principal Joanne Russell on her morning tour of classes, ducking through doorways into bright rooms with walls covered in art, numbers, vocabulary words, and hand-drawn portraits of the “classroom community.”

“Everyone in a position of leadership in this city should spend some time in a public school. It will change their outlook,” Summers said later. “We all have the extraordinary opportunity, under Mayor Menino’s strong leadership, to work together to give Boston children every chance they need to be successful. We owe it to the children and young adults of Boston to be a strong community partner.”

Summers’ transition to elementary school principal quickly turned into a new challenge – trying his hand as an elementary school teacher. Within an hour of his arrival at the school, Summers was on the floor with a circle of first-graders in Elizabeth Keenan’s math class challenging the children to think of all the ways they could make 10, using their fingers and hands as guides. Hands raised, the children volunteered their ideas – “one and nine!” said one. “Seven and three,” said another.” “Let’s check,” said Summers. “Everybody put up seven fingers. How many do you have left?” “THREE,” said the class. “Very good.”

When not interacting with the children – including partnering with a much smaller Larry to build “towers of 10” with Lego blocks – Summers was questioning the teachers who observed the day’s lessons: What was the thinking behind certain teaching methods? What were they hoping to achieve in this exercise? What did they think about the MCAS?

He commended the teachers on the job they were doing and the strategies they used to maintain order while cultivating a nurturing environment. When he asked the teachers what they thought people should know about the public schools there was a unanimous response: Boston school teachers are committed, but learning is not just about what goes on in the school. Success in learning very much depends on what happens at home.

“A lot of people say that public schools can’t work, to just forget about them,” said Ellen Guiney, executive director of Boston Plan for Excellence, the organization that coordinated the day’s visits. “We think if we can get opinion leaders like Dr. Summers into the schools to see what’s going on, we can widen the group knowledgeable about urban public schools and willing to support them. There is great teaching and great learning going on in Boston’s schools and we want people to see firsthand how they operate and the challenges faced and overcome in an urban education setting.”

After almost a dozen classroom visits and several impromptu lessons, including counting with first-graders, word-games with kindergarteners, and an introduction to collecting and analyzing data with two-line graphs for fifth-graders that principal Russell calls her “Harvard-bound crowd,” Summers rounded out the day with a discussion in the principal’s office.

“This has been a great day,” said Summers. “I’m impressed with the eagerness of the children in every classroom, from the autistic child pointing excitedly to a pumpkin in a book, to kids calling out numbers that add up to 10. They are so eager and well behaved … it really increases the sense that our society should give them every chance they can get.”

For Russell, who hopes Jackson/Mann might one day be adopted by Harvard as a “best practice” school, Summers’ visit spoke volumes about the importance of maintaining the existing relationship between the two institutions, which has already resulted in an expanded and enhanced after-school program and mentoring services.

“There is much to learn in this school about issues of importance to Harvard and the broader educational community including reducing the gap in academic achievement, preparing children for real success in an urban school system, enhancing teacher capacity through research and mentoring with and by Harvard personnel, and communicating the good works of the urban school system through writing and publishing of joint articles,” said Russell.

Before leaving the school to join Mayor Thomas M. Menino, Boston school superintendent Thomas W. Payzant, and other leaders-turned-principals to discuss the challenges of Boston’s urban schools, Summers stopped to reflect on his morning.

“Doing this every day with this many kids is a lot harder than my day job,” he said.