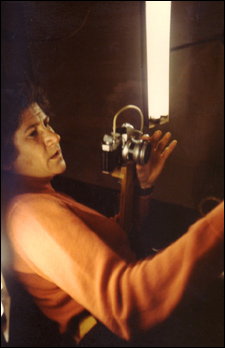

Picturing Bonnie Solomon, 72

Photographer worked at University for over 40 years

Bonnie Solomon, a photographer who worked at Harvard for more than four decades making slides of artworks for students and professors, died at her home in Cambridge Sept. 8 after a brief struggle with cancer. She was 72.

Solomon began working at Harvard in 1961. Her first job was with the Sardis expedition, documenting excavations in the ancient Anatolian city. Later that year she was hired by the Fine Arts Department, now the Department of the History of Art and Architecture.

Her job was to create slides from art reproductions for graduate and undergraduate seminar reports and for faculty lectures. Those who relied on her services appreciated her efficiency and professionalism as well as the human quality she brought to her work.

“She dealt with adolescent and young adult egos at their most fragile, and schedules at their most chaotic,” said Marjorie Cohn, acting director of the Harvard University Art Museums.

“Bonnie had strict rules about scheduling her labors but somehow she could always roll with the punches. She also somehow was always absolutely fascinated by whatever her desperate customers were thinking and writing, and somehow she made it clear that a successful end was always in sight. No one did more to to put a human touch, and a sense of humor, into what could have been the most cut-and-dried business dealing.”

Donations in Solomon’s memory may be made to Angell Memorial Hospital, 350 South Huntington Ave., Boston, MA 02130.

David Mitten, the James Loeb Professor of Classical Art and Archaeology, first met Solomon in 1961 when he was a graduate student working at Sardis and learned to appreciate the valuable service she provided for the department.

“She saved the lives and lectures and careers of hundreds of art history graduate students and professors,” he said. “I couldn’t have taught for four decades without her. She was such a positive person, equally helpful and kind and obliging to everybody, but she always said exactly what she thought and she had a way of cutting through all the guff.”

James Ackerman, the Arthur Kingsley Professor of Fine Arts Emeritus, said that Solomon “was one of those old-fashioned workers who gave much more than she took. She was an uplifting spirit who made you feel good when you were around her. She was also a communication center for the whole establishment.”

Department Chair Yve-Alain Bois, the Joseph Pulitzer Jr. Professor of Modern Art, said that Solomon was “the memory of the department. She remembered generations of graduate students, and when they would come back for visits they would always come to see her and reminisce.”

Bois also remembered that she had strong opinions and was not shy about expressing them.

“When she didn’t like something, she would let you know, and when she liked something, she would let you know as well. She sometimes had a gruff exterior, but she was gentle inside, always doing her best to help everyone.”

Albert Morales, public services supervisor at the Fine Arts Library, remembered Solomon’s concern not only for the people she worked with but for the books she photographed as well.

“She was always very strict about how she wanted things done,” he said. “She hated Post-its because they would lift up the ink from the page. She was very reliable, and she would bend over backwards for people, but she wouldn’t tolerate nonsense. Occasionally she would set someone straight if they were trying to take advantage of her, but she usually did it diplomatically and with humor.”

Born in Pittsburgh, Solomon graduated from Wellesley College in 1952 and attended graduate school at the University of Pittsburgh. She worked at Polaroid before coming to Harvard.

A lifelong animal lover, Solomon volunteered at the Franklin Park Zoo, and owned a succession of black standard poodles whom she exercised regularly at Fresh Pond in Cambridge. Cohn remembered one of her dogs and the effect it had on people at the Art Museums.

“When she started work, in a cubbyhole on the Fogg fourth floor, life was much more relaxed, and the poodle (Andy) came to work with her. Somehow seeing a happy dog in addition to a cheerful Bonnie took the edge off the most difficult, last-minute hysteria.”

She leaves a sister, Nancy Simpson of Boston, and two nephews, Jonathan Rowe of Point Reyes Station, Calif., and Matthew Rowe of Harwich, Mass.