NPR’s Garrels visits on book tour

Foreign correspondent talks about trials and tribulations of reporting from war zone

On April 9, 2003, when U.S. Marines helped an Iraqi mob pull down a 40-foot bronze statue of Saddam Hussein outside the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad, Anne Garrels was there. But her reporting of the event differed from the TV coverage that most of the American networks carried.

“It looked quite joyous on camera, but to me it was more complicated. There were many joyous people, but there were just as many on the sidelines saying, yes, but what’s next?”

‘It’s not a glamourous job. You go off for three or four months and all you do is work. That’s as long as you can stand it because you burn out.’

– Anne Garrels,

Foreign correspondent for NPR

Garrels, a foreign correspondent for National Public Radio (NPR) went to Iraq before the war started and was one of only 16 American journalists who remained after the bombing began.

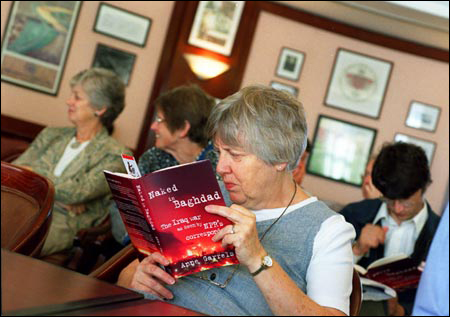

A veteran of other trouble spots including Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Chechnya, Garrels was at Harvard Sept. 30 speaking about her experiences in Iraq and reading from her new book, “Naked in Baghdad.” Her talk at the Askwith Forum was co-sponsored by the Graduate School of Education and the Nieman Foundation. She also spoke earlier in the day at the Shorenstein Center at the Kennedy School of Government.

Garrels, a 1972 Harvard graduate, emphasized that her observations came from the point of view of someone struggling with the chaos and confusion of a nation under siege and that she had little information about the U.S. government’s decision to start the war or its plan for fighting it.

But she was in a position to see how events played out as the U.S. military fought its way into Baghdad, and about this she had plenty to say.

“It was stunning to me how ill-prepared the U.S. was for the aftermath of the war. The troops believed what the Pentagon had told them, that it was not going to be that hard. They were unprepared for the incredible role they would have to play.”

This failure to plan for the postwar period resulted, Garrels claimed, in a period of chaos, rampant criminality, and lack of security that is still going on, and that has contributed to the lack of trust felt by the Iraqi people.

“I’ve been asked, why is the press giving us such a negative view of what’s happening on the ground. Well, if things are going so well, why are the civilian officials hunkered down behind barbed wire? Why haven’t nongovernmental organizations come in to help? Why hasn’t the United Nations sent more people in? The answer is, it’s just too damned dangerous. For Iraqis, the problem is very simple – security, security, security.”

Garrels said that Iraq’s infrastructure was badly in need of repair, not as a result of the bombing, which was highly accurate, but because of the years of sanctions leveled against the country. But fixing the phone and electrical systems is difficult because of the activities of criminals and saboteurs who steal transmission wires and melt down the copper to sell on the black market.

She suggested that the ongoing acts of sabotage, looting, bombing, and shooting are being carried out by a wide variety of agents, including criminals whom Saddam released from jail as the war started, foreign fighters from Algeria, Tunisia, Yemen, and Syria, whom Garrels personally saw training in special camps, and Saddam loyalists who had told Garrels that they planned to go underground if the United States drove them from power.

“There are many different aspects to it,” she said. “The borders are mostly uncontrolled. It’s not that hard to get in. A hundred and thirty thousand troops sounds like a lot, but it’s not. It’s actually less per capita than there were in Bosnia or Kosovo.”

Much of what Garrels had to say concerned the difficulties of reporting from a place like Iraq and the strategies she employed to overcome those obstacles.

“It’s not a glamourous job,” she said. “You go off for three or four months and all you do is work. That’s as long as you can stand it because you burn out.”

Garrels spoke about the oily smoke from fires Saddam’s regime set to confuse the American troops. She could not even close the windows of her hotel room because they would shatter during the bombing.

“Everyone had sore throats, and on top of that there were the sandstorms, and of course there was no water for bathing. It was pretty mucky.”

The most trying period, she said, was the two weeks leading up to the bombing, when Baghdad became “rumor central” and there was no way to answer the questions that swirled through the city. One rumor that specially concerned the broadcast journalists was that the U.S. troops had weapons that would disable all electronic devices.

“People were saying, put your satellite phone in the microwave. After all, it keeps radiation in, it should keep it out.”

Garrels said that reporting from Iraq would have been impossible without the help of the man who served as her driver and translator, a Baghdadi named Amer.

“The foreign correspondent’s secret is that wherever we work we have to find someone like Amer. Having someone like that makes a huge difference because they help you understand the society and get to the people you need to speak to. When you arrive in a new place, you’ve got to find them fast.”

Along with the devastation Garrels witnessed, there were humorous moments as well. She described a mosaic of President Bush’s scowling face that Saddam had ordered placed at the entrance of the Al Rashid Hotel so that visitors would walk over it, a grave insult in Muslim countries.

When the U.S. troops arrived, they removed it, trying at first to lift it in one piece – “probably because they wanted to sell it on eBay” – but when that failed, they removed the stones one by one.

“But after it was gone, the image of Bush’s face was still there, like the Shroud of Turin, so they cemented it over.”