Middle-class income doesn’t buy middle-class lifestyle

HLS professor sounds an alarm to families: One in seven will go bankrupt

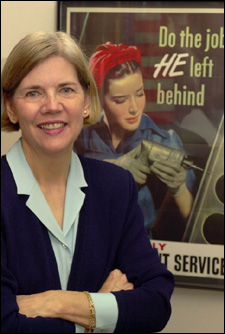

Elizabeth Warren, a portrait in soft-spoken calm as she sips tea in her gracious office at Harvard Law School, is sounding an alarm.

“The American middle class is in real trouble,” she says, her Southern-tinged sotto voce belying the power of her statement. “American families are smack up against the wall, financially speaking.” A middle-class lifestyle, she says, is increasingly out of reach for middle-class families, many of whom are going broke trying to attain it.

This startling news shouldn’t have stunned Warren, the Leo Gottlieb Professor of Law. After all, she’s been studying families, debt, and bankruptcy for nearly three decades. Yet her recent research, based in part on a survey of more than 2,000 families who had filed for bankruptcy, told a different tale from familiar bankruptcy sagas of the elderly, the young, or the profligate.

“We discovered that having a child is the single best predictor that a person will go bankrupt,” she says. By the end of this decade, one of every seven families with children will file for bankruptcy.

Even more surprising to Warren were the causes of this financial breakdown, which she assumed would implicate the battered culprit of overconsumption of luxury goods. “I thought I would write a story about too many trips to the mall, too many $200 sneakers, too many Gameboys,” says Warren.

But stacks of government data on consumer spending, which she combed through as a Radcliffe Institute Fellow in 2002, proved her hunch wrong. Compared with a generation ago, she found, today’s middle-class families earn about 75 percent more (all figures are adjusted for inflation), thanks in large part to Mom’s entrance into the work force. But after shelling out for four fixed expenses – mortgage, health insurance, child care or education, and car payments – today’s median-income family has less left over, in inflation-adjusted dollars, than the single-income family of the 1970s.

“Families are not going broke over lattes,” Warren quips. “Families are going broke over mortgages.”

‘Families are not going broke over lattes. Families are going broke over mortgages.’

– Elizabeth Warren, the Leo Gottlieb Professor of Law

Read more about Warren’s research

There goes the safety net…

Warren has reported her findings, as well as a few proposed solutions, in the book “The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Mothers and Fathers Are Going Broke” (Basic Books, 2003), which she co-authored with her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi.

The book’s title highlights a central paradox of middle-class families today versus a generation ago: While middle-class families generally need two incomes to make ends meet, it’s reliance on that second income (usually Mom’s) that’s putting them in financial peril. By counting on two incomes to fund the basics of a middle-class lifestyle – including modest homes in safe neighborhoods with good schools and high-quality child care, preschool, after-school care, or college – families have forfeited their safety nets.

“When a family builds its budget around two workers … they’re much more exposed to any economic disruption,” says Warren. A generation ago, if the sole breadwinner lost his (or her) job or became disabled, the family had a backup earner who could step into the workforce. Further, reliance on two incomes makes families twice as vulnerable to layoffs.

“The two-income family is like a speeding race car,” says Warren. “It goes faster than its one-income counterpart, but if it hits a rock, it careens out of control and crashes.”

Making those crashes all the more devastating, Warren adds, is a deregulated consumer credit industry that she calls “a monster that feeds on families in trouble.” With both incomes committed to fixed costs, families who hit a financial rock in the road turn to credit cards, mortgage refinancing, and payday lenders – often at ballooning interest costs that drag families into a spiral of debt. More and more often, bankruptcy is the only way out. This year, more children will live through their parents’ bankruptcy than their parents’ divorce.

Blame it on good schools, safe neighborhoods

How did being middle class get so expensive? The answers run contrary to popular wisdom as well as to Warren’s own assumptions. Today’s family is spending 21 percent less on clothing, 22 percent less on food – including eating out – and 44 percent less on appliances than they did a generation ago. Warren notes that a combination of lowered production costs and changing lifestyles are at work. Discount stores, meals that include less red meat and are more likely to have been purchased in bulk from wholesalers like Costco, and casual dressing at all ages have spelled savings for families.

Nor are warehouse-sized McMansions to blame; this type of housing is generally not going to middle-class families. Although housing costs have skyrocketed nationwide in the past generation, the size of average homes has grown far more modestly, by less than one room between 1975 and the late 1990s, Warren found.

Instead, Warren points the finger at two concepts dear to the hearts of almost all Americans: safety and education. Both are perceived to be more elusive now than a generation ago, when families bought a house they could afford and sent their children to the school down the street without a second thought. Now, she says, middle-class families are stretching themselves to the breaking point to afford homes in safe neighborhoods and “better” school districts.

Warren insists she’s not discussing a phenomenon exclusive to Cambridge academics or the wealthy go-getters of Boston’s tony suburbs who measure the subtle distinctions between two towns’ outstanding public schools. “I’m talking about families that are weighing the differences between Plymouth and Weymouth,” she says, describing two middle-class communities south of Boston.

Not surprisingly, improving public education is one of the policy fixes “The Two-Income Trap” recommends, along with reining in the credit industry and boosting family savings with tax policy. But families need to save themselves, she says, and trimming out the daily latte isn’t going to do the trick.

“We recommend that families take a financial fire drill,” she says. What would you do if one income disappeared? The answer, she admits, can be painful to contemplate, but she nonetheless encourages families to create a plan – savings to cover the mortgage payment for a few months, valuables to sell, a relative to move in with if circumstances dictate giving up the house – before disaster strikes and debt rages out of control.

Keeping up with the cohort

“The Two-Income Trap” is multigenerational in both analysis and authorship, thanks to Tyagi’s contribution. “She’s a Wharton-trained, hard-nosed number cruncher” who was serendipitously home with a new baby when Warren needed help analyzing the reams of government data she had uncovered.

After a few weeks as her mother’s researcher, Tyagi proposed that she step up her role and co-author the book. Mom balked. “I’m a serious academic. I don’t co-author with people from the business world, and I don’t co-author with people 22 years my junior,” says Warren. But she relented on the strength of her daughter’s argument: How better to illustrate the transformation of the American family in a single generation than to write from the point of view of two generations of a family?

Tyagi also convinced Warren that she could help bring this cautionary tale to an audience far larger than a purely academic book would reach. Reminding her mother not to refer to families as “economic units” and neighbors as “cohorts,” Tyagi brought “the ear of a popular audience to the book,” says Warren.

Describing bankruptcy as veiled in shame and silence, Warren is gratified to see “The Two-Income Trap” reaching that popular audience. She’s witnessed a media whirlwind unfamiliar to an academic author, but more powerfully, she’s listened to dozens of middle-class Americans share their stories.

“I can’t say strongly enough how decent and hardworking these people are,” she says. “The cost of being middle class has shot out of the reach of the median family. For millions of families, the situation is getting desperate.”