Summers: Will and knowledge can beat AIDS

Says Africa’s AIDS problem is not intractable

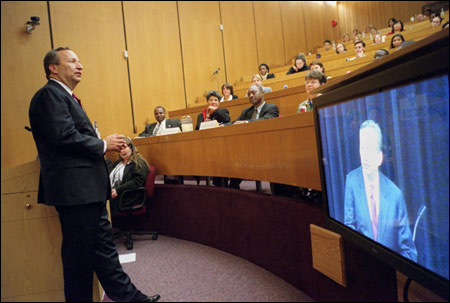

Most people are well aware that AIDS in Africa is a crisis of vast and terrible proportions. In a speech Oct. 28 at the School of Public Health (SPH), President Lawrence H. Summers declared that is it also one that offers a great deal of hope.

“This is one of the greatest challenges in the world today and also one of the most tractable, and so it behooves us to become seriously engaged.”

Summers was the featured speaker at a panel discussion titled “Public Health Crisis in Africa: How May Harvard Help?” It was sponsored by the Africa Health Forum in collaboration with the Harvard AIDS Institute.

Summers, whose practical knowledge of the developing world was enhanced by stints as vice president of development economics and chief economist of the World Bank as well as U.S. undersecretary of the treasury for international affairs, did not downplay the severity of the crisis. Rather, he described a continent where, in many areas, “life expectancy is substantially declining” and where “two teachers die of AIDS for each teacher who is trained.”

But at the same time, he emphasized that the tools to fight AIDS and other diseases ravaging the developing world are in our hands. All that is needed is the will to employ them.

“Millions of lives could be saved with today’s knowledge and resources. Many more millions could be saved with knowledge that is within our reach. This is not true of the world’s other great problems, like promoting peace or stimulating economic growth.”

Africa’s health crisis, Summers said, is part of a larger issue – the disparity between the developed and developing worlds, greater now than at any time in history. But while the standard of living for large portions of the world’s population is miserably low compared with conditions in the most prosperous countries, there have been success stories that suggest the situation is far from hopeless.

In parts of East Asia, Summers said, the standard of living has doubled in a decade, then doubled again. In China, women whose grandmothers were subject to the practice of foot-binding are making progress toward full equality. And in Seoul, child prostitution, once an acute problem, is now nearly gone.

With these successes in view, Summers said, the remaining disparities between rich and poor “offer staggering opportunities for progress.” If we accept the challenges posed by the developing world, the 21st century “could rank with the Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution” in terms of human betterment. “This looming disaster will be part of how our generation is judged by history,” he said.

Summers reminded his hearers that the arsenal for fighting AIDS and other diseases is being developed right here in the Boston and Cambridge area.

“There is a revolution under way in the life sciences, whose epicenter is a few hundred yards away from where we are right now. The city of Boston has the most concentration of talent in the life sciences of any place in the world. The world’s top five institutions in life science research are located right here.”

The knowledge developed through laboratory research has been rendered even more effective through the application of statistical techniques that have revolutionized fields as disparate as the social sciences, advertising, and even sports, he said.

“What are the most important discoveries in the history of 20th century medicine?” Summers asked. “You’d have to say penicillin, transplant surgery, chemotherapy. But equal to all of them is the double blind clinical trial, because it tells us what works and what doesn’t. The same strategy can be used in public health. We don’t have to guess anymore.”

Summers said that those who work in the university community are very lucky to be able to work on problems they find fascinating, but this good fortune implies added responsibility.

“Surely we have an obligation to the broader mass of humanity. Failure to address this crisis would be a moral failure, a failure to be a Good Samaritan, like walking past a sick person and not stopping to help.”

Summers outlined three areas in which Harvard can help deal with the health crisis in Africa. They are: developing and disseminating knowledge, training students in the life sciences and in public health and encouraging them to apply their talents to solving the developing world’s health crises, and using the convening power of the University to bring together people with insight into health issues.

Summers cited a recent example to justify his conviction that scientific knowledge can solve the health crisis in Africa if we commit ourselves to bringing that knowledge to bear.

“A tremendous thing happened last year, or rather didn’t happen. In 1918, 3 percent of the world’s population died as a result of the flu epidemic. Today, that would be 180 million people. But when SARS broke out, which is a very similar disease, less than 1,000 people died because of what we understand now that we didn’t understand then. New knowledge makes a tremendous difference in how we prevent, contain, and treat diseases.”

In addition to Summers, the panel also included Max Essex, chair of the Harvard AIDS Institute and chair of the Department of Immunology and Infectious Diseases, and School of Public Health Dean Barry R. Bloom.

Essex, who has conducted research on HIV and AIDS since the early 1980s and whom Summers earlier cited as responsible for saving numerous lives through his research and treatment efforts, spoke briefly about the AIDS crisis in Africa and what is being done to meet it.

Currently, he said, the Harvard AIDS Institute has programs in Senegal, Nigeria, Tanzania, Botswana, and South Africa. Each of these countries presents a different array of problems, thus allowing institute researchers to learn more about the disease by comparing their findings. In 2001, the institute opened a laboratory in Botswana dedicated to researching and treating AIDS. It is the largest facility in sub-Saharan Africa.

“It has allowed us to develop a model for training and to bring people together in an interdisciplinary sense,” Essex said. “Doing research on AIDS in Africa is not only important because of the tremendous need, but also because of the intellectual stimulation it provides both for Harvard students who are going there to work and for African students who are coming here.”

Bloom gave an overview of SPH programs in Africa. He said that since 1999, the School has worked in 22 countries and participated in 80 funded projects. One of the most crucial problems the School has addressed is encouraging students from poor countries to return to their homelands to work once their training at SPH is completed.

“Why don’t people go back to poor countries? Often there is nowhere to go back to where they can carry out the work they’ve been trained to do. We need long-term cooperative relationships with these countries and long-term investments in the institutions that are carrying out this work.”