Ducks, sheep, and chickens, oh my…

Ig Nobel ceremony spotlights duck sex, Murphy’s law, sheep dragging

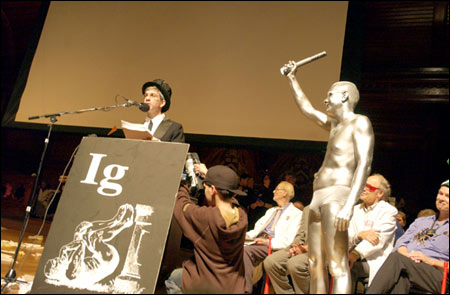

Science let its hair down in Harvard’s Sanders Theatre Thursday night (Oct. 2), laughing at its own foibles as it skewered dubious but real scientific “achievements” through the awarding of the annual Ig Nobel Prizes.

Photo gallery: The 2003 Ig Nobel Awards Ceremony

Annals of Improbable Research:

http://www.improbable.com/

Over the years, the ceremony has evolved its own schtick – a cross between the Oscars and a showing of the “Rocky Horror Picture Show.” The audience throws paper airplanes until hundreds litter the stage and the theater floor, while the onstage participants cavort through ritual operas, lectures and, of course, the awarding of awards.

Despite all the attendant silliness, the real stars of the ceremonies each year are the scientists and other recipients whose achievements, in the words of the Ig Nobels, “cannot or should not be reproduced.”

A sampling of this year’s winners includes:

The Physics Prize: for “An Analysis of the Forces Required to Drag Sheep Over Various Surfaces,” published in Applied Ergonomics;

The Interdisciplinary Research Prize: for “Chickens Prefer Beautiful Humans,” published in Human Nature;

The Biology Prize: for “The First Case of Homosexual Necrophilia in the Mallard,” published in Deinsea;

The Psychology Prize: for the report, published in Nature, “Politicians’ Uniquely Simple Personalities”;

The Chemistry Prize: for a chemical investigation of a bronze statue that doesn’t attract any pigeons;

The Economics Prize: to Karl Schwarzler and the nation of Liechtenstein, “for making it possible to rent the entire country for corporate conventions, weddings, bar mitzvahs and other gatherings”;

The Literature Prize: to a Zicklin School of Business researcher for publishing more than 80 detailed reports about annoyances and anomalies of daily life, such as the percentage of shoppers exceeding the number of items permitted in express checkout lanes; and

The Medicine Prize: for presenting evidence that the brains of London taxi drivers are more highly developed than their fellow citizens, in a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

The recipient of the Engineering Prize also delivered the night’s keynote address. Edward A. Murphy III, whose father was the “Murphy” of the famed “Murphy’s law,” accepted the award and delivered the keynote on behalf of his father.

His father, together with the late John Paul Stapp and George Nichols, formulated Murphy’s law in 1949 as a basic engineering principle whose goal, Murphy said in his speech, was serious: to ensure that people prepared for all contingencies. The law’s original language was, “If there are two or more ways to do something, and one of those ways can result in a catastrophe, someone will do it.” In other words, “If anything can go wrong, it will.”

The Peace Prize was awarded to an Indian man who lived for years as the living dead, literally. Lil Bihari of Uttar Pradesh in India, was declared dead at the instigation of unscrupulous relatives who wanted to claim his property. Bihari fought the Indian governmental bureaucracy for years before being reinstated, officially, as a living person in 1994. He has become an activist for others like him, founding the Association of Dead People.

Though Bihari was denied a visa to attend the ceremony, a representative attended and accepted the prize on his behalf.

The theme for the night’s ceremonies was “nano,” or one-billionth of something, reflecting the current popularity of nanoscience, and nanotechnology. In keeping with the ceremonies’ irreverent nature, the audience shouted “Nano!” every time anyone onstage used the term.

In addition to awarding the prizes, the ceremony also featured a mini-opera, whose subject was the ill-fated love between a scientist and an oxygen atom, of all things. It also featured the “Nano-Seminars,” consisting of brief explanations of complex or hopelessly broad subjects, such as “education,” and “chemistry.” Speakers got two cracks, flanked by a whistle-bearing umpire in with a protective mask, explaining their subjects first in 24 seconds, then in seven words.

The ceremony, sponsored by the science humor magazine, Annals of Improbable Research, the Harvard-Radcliffe Science Fiction Association, the Harvard Computer Society, and the Harvard Society of Physics Students, ended with the annual admonishment from master of ceremonies Marc Abrahams:

“If you didn’t win an Ig Nobel Prize tonight – and especially if you did – better luck next year.”