Chechnya

Nationalism to extremism

Quagmires come in all shapes and sizes. Russia’s version is a small, predominantly Muslim province in the northern Caucasus called Chechnya.

Fierce fighting between Chechen guerillas and Russian troops has taken place in this mountainous area from 1994 to 1996 and again from 1999 to the present. In recent years the conflict has escalated as terrorists and suicide bombers have attacked civilians as well as military targets.

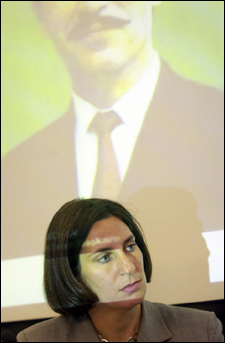

Nabi Abdullaev, a midcareer master in public administration candidate at the Kennedy School of Government, gave a talk Sept. 24 on the Chechen situation. The talk was sponsored by the Caspian Studies Program.

Abdullaev, a journalist from Dagestan, which is next door to Chechnya, has reported on the Chechen conflict for several Russian and international news organizations. In his talk titled “Chechen Self-Government: Is Islam an Obstacle?” he described a well-documented and disturbing change in the motives and methods of the Chechen rebels.

“The first Chechen war, which ended in 1996, was explicitly nationalistic,” he said. “But since then, Islamist extremists have gradually taken over the independence movement. By 1999, when the second Chechen war began, the secular agenda had all but disappeared.”

Abdullaev said that the struggle for Chechen independence has been transformed into an Islamist jihad as a result of foreign extremists infiltrating the movement. One of these was a Saudi-born guerrilla leader known as Omar bin Khattab. He and Chechen rebel leader Shamil Basayev led an invasion of neighboring Dagestan in 1999, which ended the three-year truce with Russia and brought on the second phase of the Chechen war. Bin Khattab was killed in 2002.

According to Abdullaev, there is evidence that Arab guerrillas like bin Khattab are at least ideologically linked to the terrorist organization al-Qaeda. In 2002, a videotape turned up in Afghanistan that showed both bin Khattab and Osama bin Laden speaking about the Islamic holy war against the West. In 1996, Russian police arrested Ayman Zawahiri, considered by many to be bin Laden’s most important deputy, as he tried to enter Chechnya. He was jailed for six months for entering the country without a visa.

Perhaps the most dramatic piece of evidence that Islamist extremists have taken over the Chechen independence movement came in October 2002, when Chechen rebels held 800 civilians hostage in a Moscow theater. The rebels chose to broadcast their grievances on the Arab network Al-Jazeera, which has often aired statements by bin Laden. Moreover, the women in the group were shown clad head to toe in black with only their eyes showing, a style of dress enforced by fundamentalist Muslims but entirely foreign to Chechnya.

Russian troops finally ended the hostage crisis by storming the theater, resulting in 160 deaths. Abdullaev believes that this incident resulted in a loss of sympathy for the Chechen cause.

“Since it has been taken over by Islamists and compromised by terrorism, the independence cause has all but lost hope of international recognition,” he said.

To what extent the Chechen independence movement has been taken over by Islamist infiltrators is a matter for debate. After the Moscow hostage crisis, Russian President Vladimir Putin blamed al-Qaeda for instigating and leading the attack, but others have downplayed the influence of Arab leaders.

Writing in the Times of London, Thomas de Waal, Caucasus editor with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting and co-author of “Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus,” recognized the signs of radical Islamist involvement but said, “It would be a serious mistake to make too much of the foreign factor in Chechnya.”

It is true, Abdullaev said, that Chechens tend to be clannish and independent with little regard for foreigners, and yet, he points out, it is hard to ignore the signs of radical Islamist influence in the region.

For example, after the first war, the government of independent Chechnya bandoned the Latin alphabet and adopted Arabic script, and they have replaced civil law with sharia, the code of law based on the Quran, Abdullaev said. Nevertheless, he believes there is a pragmatic basis for such changes.

“The Chechens are not happy with the Arab fighters. They don’t love aliens. But for those seeking retaliation after suffering abuse by Russian troops, the easiest choice is to join the Islamists, because that is where they get weapons, money, and protection.”

Abdullaev said that large amounts of money are being raised in Middle Eastern countries to support the Chechen rebels.

The problem with Chechnya becoming another front in the Islamist war against Western secularism, Abdullaev believes, is that it prevents the development of an indigenous Chechen elite who would be qualified to lead a self-governing Chechnya under Russian auspices. As a result of the turmoil in the region, many educated Chechens have left the Caucasus to seek a more stable life elsewhere.

“The Chechen elite is not in Chechnya,” Abdullaev said. “It’s mainly in Moscow.” But also a considerable part of it lives abroad.

Chechnya, in fact, still suffers from a shortage of human resources stemming from the exile of the entire Chechen population to Kazakhstan in 1943. Joseph Stalin ordered the exodus because he suspected Chechens of sympathizing with the Nazis and exiled even the families of soldiers fighting on the Russian front. The Chechens were allowed to return to their homeland in 1957, but they were still prevented from occupying high managerial positions in the Soviet administration.

Abdullaev believes that the way out of the Chechen quagmire is for Russia to help in the development of a Chechen elite that will be able to take over the running of the country. Russia has taken steps in this direction by drawing up a new constitution that was voted into law in a referendum in March 2003.

On Oct. 5, Chechens will vote for a new president. The Russian-backed candidate Akhmad Kadyrov is expected to win, and Abdullaev hopes that this will help turn the tide against extremism.

“What is needed is a Chechenization of power,” he said. “A secular government will become effective when it becomes Chechen business.”