Artists’ visions/versions of ancient Sardis

A city recreated on the ground and in the mind

A small map greets you as you enter the Fogg Museum’s exhibition “The City of Sardis: Approaches in Graphic Recording.”

Drawn in 1750 by Giovanni Battista Borra, an artist and architect who accompanied several other gentlemen from the Society of Dilettanti on a tour of ancient ruins in the Middle East, it is the first known map of Sardis, capital of the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor.

Created at a time when art and science were not strictly delineated, the map seems whimsical to modern eyes. It is really a drawing of a map, an exercise in trompe l’oeil, its curled and tattered edges pinned to a framed board.

Borra’s map makes a reappearance at the end of the exhibition in a way that is both startling and illuminating. A digital simulation of the terrain in which Sardis is located plays continuously on a projection screen. Based on satellite imagery, the animation shows a bird’s-eye view of the plain on which the city stands, the Pactolus Stream where the Lydians mined the gold and silver that made their kingdom one of the wealthiest in the ancient world, the looming acropolis behind the city, and the rugged mountains beyond that.

Suddenly, as the virtual camera swoops and circles, a small white rectangle emerges from the landscape below and flies upward until it nearly fills the screen. It is Borra’s map, a 250-year-old artifact, and yet as much a part of the archaeological exploration of Sardis, and the effort to render that exploration graphically, as the high-tech simulation you are watching.

For the past 45 years, Harvard has been a part of this exploration through its co-sponsorship with Cornell University of the Sardis Expedition. The bulk of the current exhibition is from the Harvard-Cornell years, but there is also enough from earlier explorations to give the presentation a sweeping chronological perspective.

In addition to Borra’s map, there is his delicate watercolor of the acropolis from ground level with some romantically crumbling ruins in the foreground, another watercolor of a ruined bridge, and some field sketches of the Temple of Artemis.

Several more artists visited the ruins during the 19th century and left records of what they saw. Charles Cockerell spent two days at Sardis in 1812 and made drawings of the Artemis temple. A visit in 1838 by Thomas Allom resulted in some accomplished etchings of the rugged hills, ruined turrets, and hookah-smoking Arabs taking their ease while their camels graze nearby.

The Temple of Artemis was begun in Hellenistic times, around 300 B.C., and remodeled by the Romans in the first century A.D. Long before that structure was built, however, the Lydians occupied Sardis and left traces that in some cases escaped notice until recent times.

In 1854, Ludwig Peter Spiegelthal, the Prussian consul in Smyrna, tunneled into a huge tumulus, or burial mound, and discovered a chamber inside lined with beautifully finished blocks of marble and limestone. This was the tomb of King Alyattes (c. 610-560 B.C.), father of Croesus, whose name, then as now, is synonymous with great wealth. Featured in the exhibition is a lithograph, based on Spiegelthal’s drawings, published in Berlin in 1859.

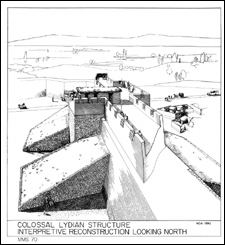

But it was not until 1976 that Cornell art history professor Andrew Ramage, associate director of the Sardis Expedition, and his wife, Nancy, professor of art history at Ithaca College, discovered a massive mud-brick wall that surrounded the city in Lydian times. Excavating and mapping the original city wall has been an ongoing challenge for the expedition up until the present, and the exhibition includes a number of diagrams as well as interpretive sketches that convey a sense of what this massive defense might have looked like.

Within that wall, many of the activities of daily life took place, none more important, from the point of view of the Lydian economy, than the refining of gold and silver. The area where this process took place was excavated during the 1960s and 1970s, and the results of those discoveries are represented by a line drawing of Lydian artisans at work. The process looks primitive, but, in fact, the Lydians must have possessed fairly sophisticated metallurgical knowledge to separate the naturally occurring compound of gold and silver called electrum into its component elements.

Lydian Sardis suffered a major catastrophe around the year 540 B.C. when the army of Cyrus the Great, king of Persia, destroyed the city. But for the archaeologist, ancient catastrophes can be causes for rejoicing, because they leave behind multitudes of buried artifacts whose positions and relationships spell out stories of the daily lives of their owners. A field sheet plan of a room in a Lydian house that suffered such destruction shows the care with which archaeologists record this data.

The Persians controlled Sardis for the next two centuries, until Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire and the city fell under Greek rule. Then in 133 B.C., the Romans took over, commanding Sardis long after the empire’s power in the West had begun to wane.

Many of the most spectacular finds belong to the Greco-Roman period, including the aforementioned Temple of Artemis, whose beautifully carved columns and capitals have continued to challenge the recording skills of artists and archaeologists. The exhibition includes a series of beautifully rendered drawings of these details from the expedition headed by Howard Butler of Princeton University, which worked at Sardis from 1910 to 1914 and again in 1922.

Among these is a pencil sketch by the talented and athletic Lansing C. Holden, who portrays himself throwing a rock with a string attached over one of the 60-foot columns. It was by this means that he was able to hoist a boson’s chair to the top of the column in order to draw the capital at close range. No member of the Harvard-Cornell expedition has ever been able to duplicate his feat.

But what the more recent team lacks in throwing ability, they more than make up for in thoroughness. A series of drawings by Fikret Yegül of the Sardis Exhibition reproduces in pen and ink every carved detail as well as every crack and blemish of the remaining two and a half columns.

Another series of drawings and photographs shows the attempts by the Sardis Expedition to reconstruct a huge marble gymnasium complex from a field of rubble. The Sardis team finally came up with a solution to this vast jigsaw puzzle in 1967, and an on-site reconstruction was completed several years later.

The largest ancient synagogue ever discovered was unearthed in Sardis, a reflection of the city’s large Jewish population. The elaborate building with its spectacular mosaic floor is represented by drawings, diagrams, and a three-dimensional model loaned by Yeshiva University.

The last items in the exhibition show how digital technology is taking over from the older paper-based methods of recording, culminating in the virtual mapping project and a digitized reconstruction of a painted Lydian tomb. But whatever the tools employed, whether pencil, pen, or computer, the results demonstrate the enduring human desire to recover and understand our past.