Activist Larry Kramer is not nice

Kramer urges KSG students to ACT UP: ‘Confront the system. Take no prisoners.’

Larry Kramer, writer and AIDS activist, doesn’t believe leadership can be taught. “We really made it up every day as we went along,” he said of his years with ACT UP, the international AIDS advocacy and protest organization he founded. “If I were to teach anything here it would be how to confront the system, not work within it. Hit it over the head with a bat and take no prisoners.”

Such bold, iconoclastic statements, while not surprising to anyone familiar with Kramer’s activism, struck an ironic chord at his Sept. 30 talk, which was sponsored by the Center for Public Leadership at the Kennedy School of Government (KSG). Yet even as he dismissed both “leadership” and “government” as ineffectual avenues for change, Kramer charmed the standing-room-only audience at the Charles Hotel with his quiet wit and fearless outspokenness.

Kramer was an accidental leader, thrown into action in the earliest days of the AIDS epidemic when his friends began getting infected. “I was just a New York faggot like everyone else who was gay then,” he said. “I didn’t march in Pride. We used to be at Fire Island and make fun of all that.” An accomplished playwright, screenwriter, novelist, and journalist, Kramer described himself as an essentially shy person who “gets nervous when I’m away from my computer.” He won an Obie Award for his 1993 play “The Destiny of Me,” which was also a runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize, and his screenplay for the film “Women in Love” (1969) was nominated for an Academy Award.

Motivated by fear, as AIDS threatened the lives of his friends, and fueled by anger at government and policy inaction against the epidemic, Kramer co-founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the first and world’s largest service provider to people with AIDS, in 1981. Frustrated by that organization’s nonconfrontational nature, he launched the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power – ACT UP – in 1987, leading a grassroots effort to accelerate the approval process for drugs to treat AIDS. At its height from the late-1980s to the mid-1990s, ACT UP boasted 140 chapters nationwide.

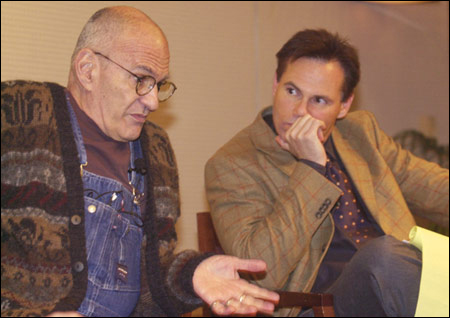

Despite his ongoing success as an activist, Kramer had few traditional leadership tips to share. “I’m a very instinctive person, and prickly,” said Kramer in the easygoing discussion with Jonathan Katz, executive coordinator of the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies at Yale University. “Everything I said is out of my own passion.”

Casually distinctive in bib overalls and a cardigan sweater, Kramer encouraged the audience of students and faculty from Harvard College, the KSG, and other graduate schools to find their passion in anger, focus their activism, and circumvent traditional leadership counsel for confrontational techniques. Coalition building, he said, is “very nice” but difficult to achieve in the real world. “People in groups don’t behave well, and there’s nothing you can do about it,” he said.

Still, Kramer and ACT UP tempered their guerilla-style actions with high-level negotiations, often playing both good cop and bad cop to great success. “You have to be the enemy and get behind enemy lines,” he said. “They’ve got to be frightened of you.”

Similarly, he and fellow activists educated themselves on the considerable science and politics of drugs and drug approvals. “We knew what we were talking about. We knew more about the science and medicine of AIDS than the scientists and doctors did,” he said.

ACT UP is now a much smaller organization than it was 10 years ago, and Kramer sees confrontational activism in general on the decline. He’s frustrated, he said, by complacency about AIDS in this country.

“It’s heartbreaking to see infections on the rise again in the gay world when people know better now,” he said. “It’s like a slap in the face to everyone who died. We didn’t fight like hell to get you the medicine so that you could go out and get infected.”

To a KSG student who asked how to address the overwhelming AIDS epidemic in her native Kenya, Kramer delivered a response he warned she wouldn’t like.

“There’s remarkably little activism of a confrontational nature in these countries,” he said of Africa. “Your people have to be made to shove it in their faces. Tie up governments, tie up industry, tie up traffic. Pour fake blood in department stores.”

Kramer’s brand of activism trades politeness and diplomatic savvy – qualities arguably embraced by many in the audience – for shock value and confrontation.

“You do not get more with honey than with vinegar. You get it by being harsh and demanding and in-your-face – constantly,” he said. “We’re all anxious to have everyone love us. It’s difficult to maintain that if you have strong opinions.”