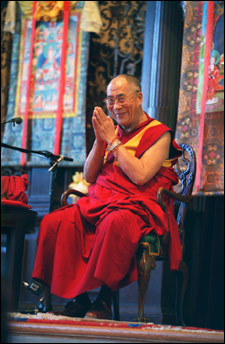

‘Simple Buddhist monk’ fills the Memorial Church:

The Dalai Lama talks sense to devotees, admirers

Tibetan Buddhism, with its pantheon of gods and demons, its elaborate rituals, colorful costumes, and esoteric meditation techniques, seems, to Westerners at least, to be the most exotic manifestation of the religion founded by Siddhartha Gautama 2,500 years ago.

But those who came to hear the Dalai Lama’s talk at the Memorial Church on Sept. 15 hoping for an explication of these traditions and practices may have been disappointed. What they heard instead was some down-to-earth, commonsense advice from a man introducing himself as “just a simple Buddhist monk, no more, no less.”

Full Dalai Lama visit archives: videos, photo galleries, articles, and transcripts

The Dalai Lama is traditionally considered both head of state and spiritual leader of the Tibetan people. He is also thought to be a manifestation of the Bodhisattva or Buddha of Compassion. But this Dalai Lama, the 14th of his line, who has lived in exile since the Chinese crushed a Tibetan uprising in 1959, emphatically downplayed these supernatural credentials.

“Some call me a god-king. That is nonsense. Others call me the living Buddha. That is also nonsense. Deep in my mind I consider myself to be a Buddhist monk. Never in my dreams do I consider myself to be the Dalai Lama.”

The Tibetan leader and 1989 Nobel Peace Prize winner spent the day at Harvard after consecrating a Tibetan Buddhist temple in Medford, taking part in a conference on the mind-body connection at M.I.T., and speaking to a capacity crowd at the FleetCenter. The Boston visit was part of a 20-day U.S. tour.

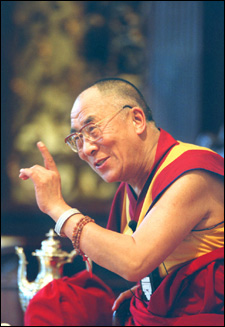

Rather than stress the differences between Tibetan and Western belief systems, the Dalai Lama repeatedly emphasized common areas.

“I am a human being. You too. We are the same. Emotionally and mentally, we are the same… Since we are the same, therefore everyone has the same desire for a happy life. From birth, all have the right to have a happy life.”

What is the key to happiness? Like so much else, it begins in early childhood, with a baby’s relationship to its mother.

“We learn affection from our mother, not a guru. The guru comes later. First we receive the lesson of compassion from our mother by example.”

This lesson, he explained, comes from the simple act of sucking milk from the mother’s breast. The child learns about compassion and altruism by realizing that its mother is giving of herself.

The Dalai Lama, who spoke partly in English and partly in Tibetan through a translator, had some trouble recalling the anatomical terminology for this relationship. But the bonds formed are powerful, he emphasized. He said that his own father, until the age of 10, would beg (unsuccessfully) to drink from his mother’s breast.

“When the family provides affection,” he said, “the mind is much more stable, the ability to study is better. The worst thing is when young people grow up without affection. This makes it very difficult to show others human compassion. Their whole life becomes very dry.”

The Dalai Lama related a story from his own early life that showed that compassion may be difficult to internalize, even for someone who is held to be the manifestation of the Bodhisattva.

As a young boy he envied his teacher’s relationship with a pet parrot. The parrot would greet the teacher, take food from his fingers, and allow him to stroke its head.

“I wanted that from the parrot. I tried to give the parrot nuts, but it took them very aggressively. I tried to touch him, and he bit me. I lost my temper and I took a small stick and hit him.”

The experience taught him that anger and other negative emotions are self-defeating.

“Hatred and violence bring disaster. If there is too much hatred, you lose your digestion, you lose sleep, you lose health, eventually you lose your family.

If you have an irritating neighbor, you only hurt yourself by giving way to negative emotions, he said.

“It spoils your peace of mind. You become an agitated person. The neighbor has succeeded because your own negative emotions have harmed you.”

The Dalai Lama said that he cultivates peace of mind in his own life by meditating five hours every day. This practice helps him maintain a good mood, which makes it easier for him to deal with daily problems.

He said that the advantages of maintaining compassion and peace of mind were demonstrated by scientists who examined Tibetan monks who had spent years in Chinese prisons.

“They found that there were no signs of trauma in these monks. One monk said there were only a few occasions when he faced real danger. What kind of danger? He said, the danger of losing compassion for the Chinese.”

Without compassion, the brain power that distinguishes humans from other animals can be a destructive force, he said.

“A very brilliant brain, when used the wrong way, can become very cruel, as in the Holocaust.”

The attacks on 9/11 were another example of intelligence gone awry, he said.

“One can be sure that in the planning of those attacks there were many calculations, with many devious means. People used their brains in a very sophisticated way. It was modern technology guided by human hatred.”