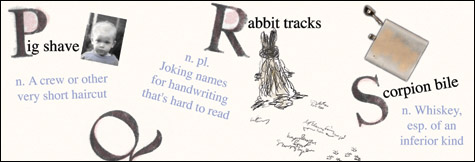

You don’t say:

A DARE-ing dictionary of words you may never use

A former boss of mine once called me a “scissor-bill.” I concluded that it was not a term of endearment, but I didn’t know what it meant.

Ordinary dictionaries were no help. Then I came across DARE, the Dictionary of American Regional English. “A foolish, incompetent, or inexperienced person” was one definition of scissor-bill and, as I recalled the look on my former boss’s face, I was sure he meant all three. (Alaskan Indians have also used the word to refer to white people.)

DARE also gives meaning to words such as “dickety-boo” (a ghost), “flyuppity” (quick-tempered), “pinkletink” (a young frog), and “dropped egg” (poached egg).

Besides shedding light on mind-teasing and sense-pleasing expressions, it’s a fun book to browse through – all four volumes. Hundreds of maps show where the expressions originate, and the words are used in sentences. For example, you are most likely to hear “Martha ate her toast and dropped egg” in the Northeast, particularly Maine.

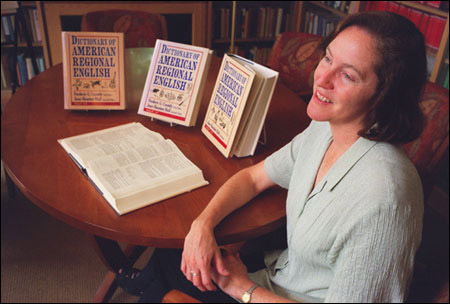

“DARE is much more than a word list,” says Jennifer Snodgrass, reference editor and custodian of the dictionary project for the Harvard University Press, which publishes it. “It’s a portrait of American language. It’s a great resource, not only for librarians and scholars, but also for writers and for those who want to find out what grandma meant when she used words like ‘quiddle’ (to trifle or fuss). Law enforcement agencies have used it to search for regional clues in ransom notes, and dialogue coaches draw upon it to prepare Broadway actors for parts that require regional accents.”

“We all assume we speak the same language,” notes Joan Hall, chief editor of DARE, which is put together at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “But we are constantly surprised by its wonderful regional variations. DARE is a record of these variations.”

Breasts and chippies

DARE is no short-term project. Frederic Cassidy, a word lover at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, began serious work on the dictionary in 1963. Forty years later, four volumes have been published covering words beginning with letters from A to Sk. Volume 5, from Sl to Z, is expected to be out in 2008. A sixth volume, scheduled for 2010, will include an index, questions fieldworkers asked people all over the country to find regional words, and other information.

But deadlines have a way of slipping. Cassidy thought the project would be finished by 1989 (long before his death in May 2000). But it took longer to gather the expressions, and to find money to pay for the search, than he thought.

Fieldwork began in earnest in 1965 when a $550,000 grant enabled Cassidy to send 80 people, 51 men and 29 women, all over the United States. They visited 1,002 communities and somehow talked 2,777 people (from ages 18 to 90 years) into answering a questionnaire with 1,847 queries about food, farm animals, hunting, fishing, flowers, birds, bugs, dishonesty/honesty, tobacco, liquor, courtship, joking names for the local sheriff, and body parts.

One question about other names for women’s breasts gave everyone a pause. The U.S. Office of Education, which funded the fieldwork, wanted the question removed. Cassidy refused. The Office of Education finally relented. “We could talk about such things because we talked about them (only) as words,” noted one of Cassidy’s collaborators.

Still, some interviewees were embarrassed about discussing certain terms. When asked what he would call a woman who had many boyfriends, one man said he couldn’t use the word in front of his wife. When he and the interviewer went out in the hall, the man whispered, “They’re called chippies.”

Fieldworkers called the vehicles they drove “word wagons.” They carried pads of 4-by-6-inch slips so they could write down new words they heard in stores, restaurants, bars, and on the street. They recorded interviews on awkward, suitcase-sized, reel-to-reel recorders.

Commenting on the effort, Mark Johnson wrote in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel on Oct. 14, 2001: “A national self-portrait is emerging from the dictionary’s uncompromising look at American speech, from the beautiful to the ugly, from the 79 different regional terms for ‘dragonfly’ to the 13 pages of entries concerning the word ‘nigger.’”

Ozzy, peeny, and pip

The road worders collected close to 2.5 million pieces of information during five years. One of them later called it the most interesting time of his life.

Twenty years after the fieldwork began, in 1985, the first volume, covering only A to C, was published. It contained 1,059 pages and cost $50.

Joan Hall particularly remembers one word in that volume – “bobbasheely.” In searching for more information about its use and origin, she found it used as a verb in the William Faulkner novel, “The Reivers,” to indicate a close relationship between two people. Further investigation revealed that it originated as a Choctaw Indian word meaning “my brother with whom I was suckled.”

“Such findings provide remarkable ‘aha!’ moments that make DARE so much fun to work on,” Hall comments.

Volume II came out in 1991 with 1,175 pages. It began with “d,” a euphemism for the devil and finished with “hyuh,” a Southern substitute for “here.” Volume III followed in 1996. It ended with “ozzy,” a word people in Wisconsin use for “strange looking” or “peculiar.”

Volume IV debuted last December. It contains terms such as “on pump,” which means “on credit.” It notes that a “potluck dinner” is likely to be called a “pitch-in” in Indiana or a “scramble” in parts of Illinois. To test your skill at matching meanings with Volume IV words like “peeny,” “pip,” “rimrack,” “ruddle,” and “semmel,” you can take an online quiz at http://polyglot.lss.wisc.edu/dare/quiz4.html.

Hall says that her favorite Volume V words include “sollaker,” which means “whopper, impressive” in Vermont, “splunge,” for “plunge” in some parts of the South, and “spatgie,” a regionalism for sparrow.

The DARE office in Madison keeps updating the field survey with words from regional magazines, newspapers, newsletters, and even novels. The office also handles a voluminous flow of incoming and outgoing queries. It solicits additional information about specific terms and tries to contact people who grow up in certain areas through its DARE Newsletter.

You can also hear samples of recordings made by the original word workers, which demonstrate how pronunciations varied from region to region. Different people read the same story about Arthur the Rat, a tale designed to elicit various sounds made by English speakers. These recordings can be accessed at the same Web address as the quiz.

Snodgrass points out that the project experienced “a number of funding crises through the years, although it is now amply supported by federal and private grants.” In the early 1970s, the Harvard University Press agreed to publish all the volumes and to market DARE. It has stood by that agreement through the financial troubles and slipping deadlines.

“We will not abandon the project,” Snodgrass says firmly. “We’re not into it for the money; we might break even but it’s impossible to tell at this point. [Each volume now sells for $89.95.] In some ways the dictionary is irreplaceable; the original survey couldn’t be done now because society has become so mobile and mixed. It’s a service to scholarship and it’s also a lot of fun.”