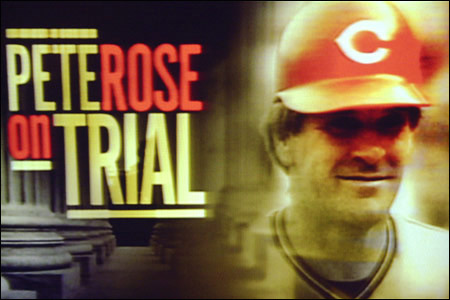

Should Pete Rose be in the Hall of Fame?:

Jury in mock trial at Harvard Law School says ‘yes’

Let him in!

That was the jury’s decision in a mock trial to decide whether Pete Rose should be admitted to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y. The trial took place July 17 at Harvard Law School.

Broadcast by the cable sports channel, ESPN, the trial featured Alan Dershowitz, the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law, for the prosecution and high-profile Los Angeles lawyer Johnny Cochran for the defense. Former Texas state judge Katherine Crier, now a TV journalist, presided.

The trial took place in Ames Courtroom in Austin Hall, which was transformed into a television studio for the occasion with banks of lights glaring down from the ceiling and a TV camera, one of several, swinging over the audience on a 30-foot boom.

Rose himself was not present, although several well-known former ballplayers, teammates or opponents of Rose, appeared as witnesses. They included Dodgers and Padres infielder Steve Garvey, Reds outfielder Dave Parker, and Red Sox pitcher Bill “Spaceman” Lee. Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer and home run record-holder Hank Aaron gave testimony via videotape.

In 1989, then-baseball commissioner Bart Giamatti barred Pete Rose from baseball after an investigation found that he was guilty of betting on baseball games, including those involving his own team, the Cincinnati Reds. Rose had retired from active play and was managing the Reds at the time.

The decision was controversial because the evidence presented was circumstantial. Rose, who was alleged to have been heavily in debt as a result of a gambling addiction, has admitted to betting on other sporting events but to this day he denies that he ever bet on baseball. In view of his playing career (he holds the record for hits, singles, at-bats, and games played), there is little or no disagreement that if it were not for the gambling issue, Rose would deserve a place in the Hall of Fame.

Although the trial had no official bearing on Rose’s status except as an indication of public opinion, both lawyers played their parts with thoroughness and conviction.

In his opening arguments, Dershowitz stated that despite Rose’s “extraordinary talents as a ballplayer,” he had violated baseball’s sacrosanct rule: “Thou shalt not bet on baseball, especially not on a game in which you play.” He promised that during the trial he would show the jury incontrovertible evidence of Rose’s guilt, including phone conversations with bookies and a betting slip marked with Rose’s fingerprint.

Cochran focused on what he contended was the unfairness of the procedure by which Rose was ruled ineligible for the Hall of Fame. After a lengthy investigation, Rose had signed an agreement barring him from baseball but without stating explicitly whether he was guilty of gambling. Rose’s understanding at the time was that the agreement did not bar him from having his plaque installed at Cooperstown, but a change in the rules two years later stated that players who had been barred from the game were also ineligible for induction into the Hall of Fame.

The witnesses called by each side were evenly matched – an assortment of retired players, sports writers, and experts on addictive gambling.

Dan Shaughnessy, a sports columnist for The Boston Globe, recalled Red Sox first baseman Bill Buckner’s fatal error in the 1986 World Series as an example of baseball’s reputation for honesty and integrity, a reputation that gambling would undermine.

“When Bill Buckner let that ball go through his legs in the sixth game of the World Series, no one thought that he had thrown the game because of the trust that baseball has earned.”

Dershowitz replied: “You’re the only person who has ever found anything good to say about Buckner’s error.”

Former Red Sox pitcher Bill Lee drew laughter and applause with his outspoken testimony. Asked for his opinion of Rose, he responded, “He’s a pain in the ass, but he’s one of the greatest two-strike hitters I’ve ever seen. He’s the kind of guy you hate, but if you want to build a ballclub, he’s a guy you’d want.”

Asked whether he thought Rose should be admitted to the Hall of Fame, Lee replied, “I’m not going to hang the guy … unless I can do it myself.”

A moment of drama occurred when Dershowitz cross-examined Cochran’s witness Bill James, whose book on the controversy tends to exonerate Rose. Dershowitz challenged James’ contention that a witness against Rose had flunked a lie detector test.

“That’s not true!” Dershowitz said, his voice rising. “You made that up! Did she take a test and fail it, or did you make a serious mistake?”

But despite Dershowitz’s forceful presentation, the decision of the jury went against him. Jury member Lewis Rice, editor of the Harvard Law School Bulletin, said he was unconvinced that allowing Rose into the Hall of Fame would affect the integrity of baseball.

“I thought that allowing Rose to work in baseball and having him in the Hall of Fame are separate issues,” he said.