Despite economy, PBHA camps thrive:

PBHA summer program mixes recreation and education for area youth

Preparing for their positions as co-directors of a Phillips Brooks House Association (PBHA) summer day camp, Kristin Garcia ’05 and Chris Vena ’05 had a jam-packed semester this past spring. Into their Harvard studies they shoehorned the sorts of real-world duties that would make their camp – the Franklin I-O Summer Program in Dorchester – a success.

They carefully recruited a staff of seven college students from the 100 applicants for the job. They secured a new – and with air-conditioning, greatly improved – site for their camp at the Epiphany School in Dorchester. They wrote grants to fund the camp’s $40,000 budget, then filled in gaps with in-kind donations from community vendors and organizations. They developed a curriculum that mixed academic rigor with project-based learning and threw in swimming, camping, and field trips for pure summertime fun.

What they didn’t need to do, however, was recruit their 70 campers. At just $75 per camper for the eight-week session, Franklin I-O and all the PBHA camps are the lowest-cost summer programs in the Boston area.

As the region’s beleaguered economy takes its toll on programs for low-income families and youth, all 12 of the PBHA-sponsored summer camps, including the Franklin I-O, saw their waiting lists swell larger and earlier than in previous years. At the same time, the camps have struggled with fundraising; long-time sources of income have decreased their support or disappeared altogether. Still, 850 Cambridge and Boston youth have enjoyed safe, enriching summer fun at PBHA camps in their neighborhoods.

“We’re dealing with these government budget cuts that were out of our control,” says PBHA Director Ayirini Fonseca-Sabune ’04, herself a former director of the Keylatch Summer Program in Boston’s South End. “I’m really proud of our directors, because we haven’t cut back on services to kids”

Fonseca-Sabune also notes that Harvard stepped in to relieve one of the most crushing blows dealt by municipal government budget woes: the serious cutbacks to the youth employment funds that paid salaries for the camps’ high school-aged junior counselors. Through the Office of Government, Community, and Public Affairs, the University granted the camps $50,000 to support these vital positions.

Community partnership, not charity

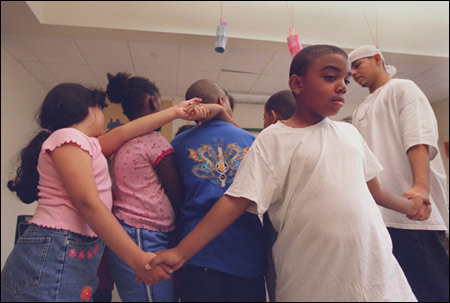

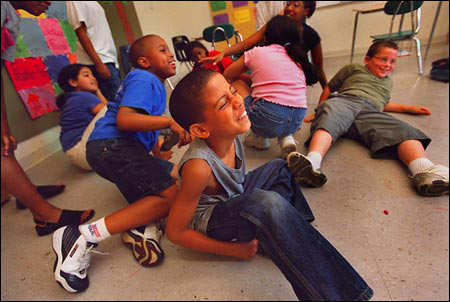

At Franklin I-O camp (“I-O” stands for “inner-city outreach,” an expression no longer in vogue but part of the camp’s tradition) one steamy morning in July, budget cuts seem far from anyone’s mind. Upstairs in a classroom, counselor Tanya Thompson ’06 has her 8-year-old charges in knots. Literally: They’ve created a human knot by grabbing hands across a circle – and untangling it is putting their cooperation skills to the test.

“We’ve got to communicate,” says Thompson as the pretzeled jumble of limbs falls to the linoleum in a heap. “When we get this, we’re going to be so proud.” Indeed, when they finally succeed in untying the knot, after several tries, there are high-fives all around.

Later in the morning, that same group will turn newspapers, paper towel tubes, baking soda, and vinegar into volcanoes that erupt as they shriek with surprise.

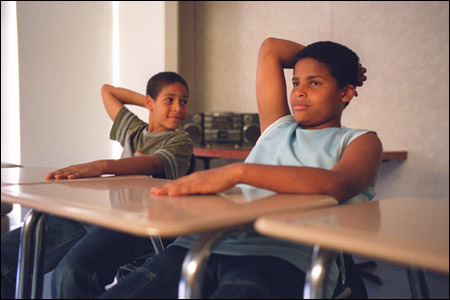

Downstairs, 11- to 13-year-old boys prepare to make pinhole cameras. An experiment squarely at the intersection of science and cool plays with light and vision to help them understand how their homemade cameras will produce images.

Garcia and Vena are ubiquitous, juggling cell phone calls, planning an afternoon visit to the State House, dispensing an ice pack to a mildly injured camper. Both were counselors at Franklin I-O last summer and tutor many of the same children during the year through PBHA’s Franklin Afterschool Enrichment (FASE) program, which Garcia directed.

“That’s a great part of our program: we can maintain this connection with the kids year-round,” says Vena. “We pride ourselves on being involved with the kids, their families, and the community.”

Involved, yes, but as a partner, not a charity. It’s an ethic that pervades all the PBHA camps.

“There’s a real spirit of ‘we’re not coming here to do things for you,’” says Gene Corbin, the new staff executive director of the student-run PBHA. “There’s a real sense of community partnership and ownership.”

At Franklin I-O, creating that sense of ownership is at the core of the vision that Vena and Garcia outlined for the camp in the spring. They instill it by demanding that the campers show respect for each other, for the counselors, and even for the shining new Epiphany School building they use at a reduced cost.

“We try to hold them accountable to the future of the camp program,” says Vena. “Even the 6-year-olds get that.”

Junior counselors, the 14- to 17-year-olds from the community whose positions were so jeopardized by city budget cuts, play an important role in the legacy of the camps, Vena points out. Most of them rose through the camps as campers and some continue on to become counselors when they advance to college. The PBHA camps provide the 85 youths not only with valuable summer employment, but also with job skills, mentoring, and even a term-time tutoring program that extends their access to Harvard and PBHA.

Junior Feliciano, 16, is easy and outgoing as he disengages himself from the “human knot” of his 8-year-old charges. The former camper and resident of the Franklin Field Development admits that his summer would look a lot different had he not returned to Franklin I-O for his second year as a junior counselor. “I’d be working at CVS or trying to find a job,” he says. “But of course I wanted to work at this job first.”

It’s not hard to see that the job has served him well; Feliciano swells with pride as he recounts the skills it’s granted him.

“I’ve got experience, I know how to control my kids. I make sure they’re safe at all times so their parents won’t worry,” he says. “I learned that I’m a good leader.”

A summer to savor

Several weeks later, at Stony Brook Park in Jamaica Plain, Feliciano and his junior counselor colleagues are hard at work staffing booths and directing dance routines at the camps’ mid-summer celebration. Campers, counselors, and parents and friends of all 12 PBHA camps have gathered for the annual celebration; this year, the junior counselors have taken the lead on organizing the festival.

“Responsibility for the event provided a valuable opportunity for the younger staff to develop their leadership skills,” says PBHA’s Fonseca-Sabune, and by all accounts, they’ve succeeded. Kids and families from all over Boston and Cambridge run three-legged races, eat cotton candy, and have their faces painted and their fortunes told. A long line snakes around tables groaning with food donated by local vendors. A DJ pumps out hip-hop tunes before surrendering the stage to talented representatives from each camp.

Feliciano, who’s helped coordinate the talent show, surveys the scene with satisfaction. “I learned that organization is the key to everything,” he says of his duties.

Garcia, too, watches proudly, snapping photos and savoring the few weeks remaining with her campers. “I’m learning how to love,” she says, wincing at her own corniness but adding that love means not just giving hugs but getting angry, too. It’s a life lesson gleaned from a classroom far outside Harvard Yard.

“My college experience wouldn’t be complete without all this,” she says.