When men were men (and women, too):

Through playbills, posters, photos, ‘Cross-Dressing on the Stage’ brings history to life

Cross-dressing in the theater has a long and fascinating history, going back at least to the ancient Greeks. This summer, the Harvard Theatre Collection is presenting an exhibition that brings this history to life through rare playbills, posters, and photographs. The exhibition is open to the public in the Edward Sheldon Exhibition Rooms in Pusey Library.

Honorary Curator Laurence Senelick, the Fletcher Professor of Oratory at Tufts University and author of “The Changing Room: Sex, Drag, and Theatre,” gave a lecture on the subject June 18 that helped to explain why the spectacle of a man playing a woman or vice versa has had such a long run in the theater.

“From the dawn of time, women’s presence in the theater has been the exception rather than the rule,” said Senelick. “The theater is grounded in religion, and having women on stage was not considered decorous. Their realm is the home.”

The irony is that the religion from which ancient Greek theater sprang was the worship of Dionysus, the god of ecstasy whose rites were carried out principally by women. But when these rites evolved into theater, women were banished from the stage and their parts taken by men. The Greeks believed that allowing women to perform publicly would be too dangerous and that having men portray them neutralized the danger.

The ban against women on stage, initiated by the Greeks and bolstered by the Christian insistence on female chastity, remained in force until the 17th century when female singers began to appear in a new form of musical theater called opera.

Christian authorities were not happy with the new development. Pope Clement XI said, “A beautiful woman who sings on stage and keeps her chastity is like a man who leaps into the Tiber and keeps his feet dry.”

Rather than condone the outrage of female performers, the Church employed male castrati to sing soprano parts. Although ostensibly prohibited since 1587, castrati continued to perform in the papal choir until the late 19th century.

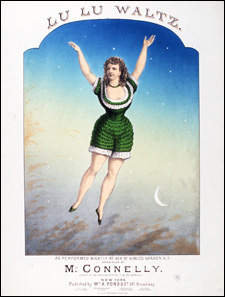

One might expect the admission of women on stage to be related to a demand for greater realism, but the actual result was not only that men and women got to play roles appropriate to their gender, but that the impersonation of the opposite sex could now go both ways. During the Restoration period, there was a vogue for women playing male rakes like Macheath in John Gay’s “The Beggar’s Opera.” Based on the playbills and advertisements that have survived from this period, the male attire these women wore did little to conceal their feminine contours, which seems to have been the point.

Relieved of the necessity of playing young women on stage, males who specialized in playing characters of the opposite sex now did so largely for comic effect, often portraying older women or women of the lower classes. As in the ancient Greek theatre, this tradition reflected a fear of female sexuality.

“The menopausal woman was considered dangerous if she was sexual. Treating her comically and having her played by a man has the effect of neutralizing her,” Senelick said.

Even in our relatively liberated age, seeing two women kiss on stage or on the screen can be a bit shocking. But during the 19th century, as the stage became less bawdy and more genteel, depictions of sexuality were considered more acceptable when both partners were women. A number of actresses such as the British Helen Weston, specialized in playing romantic male roles.

Also popular at this time were women playing young boys, especially those of the lower classes – chimney sweeps, newsboys, characters whose appealing vulnerability could be enhanced by casting a woman in the role. As Senelick pointed out, the ultimate example of this strategy is the traditional casting of a woman in the role of Peter Pan.

“He’s a pirate, the leader of the lost boys; he can fly, he’s the bravest kid around, and what he wants most in the world is a mother.”

In America, the all-male minstrel show also used female impersonation as a way of appeasing straitlaced provincial audiences at the same time as it perpetuated racist stereotypes.

“The fact that the minstrel shows were all male meant that they were wholesome, clean entertainment. There were no loose women and therefore no danger of pollution from the stage.”

Some of the most popular plays of the 19th and 20th centuries have featured men impersonating women, usually out of necessity rather than choice. “Charley’s Aunt” by Brandon Thomas (debuted on Broadway in 1893 and revived many times since) is a prime example of the genre. More recent versions of this basic device include “I Was a Male War Bride” with Cary Grant, “Some Like It Hot” with Tony Curtis and Jack Lemon, and the 1980s television show “Bosom Buddies” starring Peter Scolari and Tom Hanks.

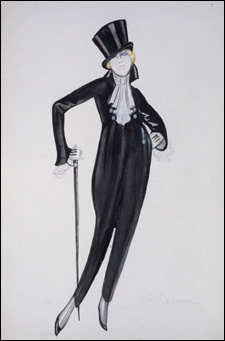

In the early 20th century, several popular male impersonators emerged from the homosexual subculture. Annie Hindle and Ellen Westman each created long-running stage acts in which they convincingly portrayed rough, boisterous men-about-town. In England, Vesta Tilley honed a similar stage personality, although her characters tended to be more genteel.

“Glamour drag,” a genre that grew in popularity during the first half of the century, began with such performers as the vaudeville star Julian Eltinge, who insisted he was a “man’s man” in his private life, and the comedian Bert Savoy, considered to be a model for Mae West. Savoy’s last words, before being struck by lightning during a thunderstorm, were reported to be, “Goodness, ain’t Miss God actin’ up!”

Is the goal of theatrical cross-dressing to confuse or deceive us? Senelick does not think so.

“Gender impersonation should not be seen as an attempt to imitate the other sex, but rather as an effort to combine elements and create something fresh, but something that cannot be experienced outside the theater.”

The Harvard Theatre Collection presents ‘Cross-Dressing on the Stage,’ an exhibition of rare playbills, posters, and photographs. The exhibition is open to the public in the Edward Sheldon Exhibition Rooms in Pusey Library through Sept. 12.