Sachin Shivaram welcomes the burden of privilege at Harvard:

Between extra courses and advocacy work, there’s still time to run marathons

In his sophomore year, Sachin Shivaram ’03 spotted a course at the Kennedy School of Government that sounded tailor-made to his interests: “Race, Class, and Poverty in Urban America,” taught by sociologist William Julius Wilson.

Admission to the small course of just 25 students was by essay. Competing against KSG graduate students, Shivaram’s essay didn’t even put him on the alternate list. Still, he was undaunted.

“I really wanted to take the class, so I pestered the professor,” he says, adding that he read two of Wilson’s books in advance of the class and proposed that he meet weekly with the professor to discuss the course’s readings.

When Wilson, the Lewis P. and Linda L. Geyser University Professor, didn’t respond, Shivaram trained his determination on the course assistant, who told him that fire codes prevented even one more student to join the class.

So Shivaram investigated the fire codes for the room and found that, in fact, the room’s capacity was 54 people. He was admitted to the course and, despite his rocky start, forged a rewarding relationship with Wilson.

“We turned out to be really good friends, and he’s one of my closest advisers,” says Shivaram, who concentrated in history and literature and African-American studies.

Shivaram calls Wilson’s course the highlight of his Harvard academic career: no faint compliment, given the competition. While most students will graduate today with 32 credits, Shivaram – who was inducted into Phi Beta Kappa – boasts 44, the product of taking an extra class or two almost every semester.

The hefty course load had less to do with resume padding or bragging rights, says Shivaram, than about the same tenacious thirst for learning that saw him shoehorned into Wilson’s class.

“I know how valuable the professors here are, and every student is just so smart,” he says. “There are so many resources here available to us. Once you realize that, it’s a responsibility to go out and make use of them.”

Helping the powerless find a voice

While his intellectual curiosity has led Shivaram down several academic paths (languages – he’s studied Spanish, Portuguese, and Arabic at Harvard – have held a particular appeal), Wilson’s course resonated with the student’s broader purpose and values: helping the powerless and the oppressed find a voice.

“I don’t like seeing people struggling alone,” says Shivaram. “It makes me feel that they need community, they need an advocate. Not someone to speak for them, but someone to get their own voices out. I really want to be a conduit for that.”

At Harvard, Shivaram has focused his energy on civil rights and women’s rights, blending activism, academics, and public service to lead, ultimately, to policy solutions. He’s been involved with the NAACP since high school in his hometown of Milwaukee, and he continued his work at Harvard and with the Boston and Cambridge chapters. He was a researcher with Harvard’s Civil Rights Project for a year.

Working with poor, abused, and otherwise in-crisis women through the local shelter On the Rise and Lewis A. Horvitz Professor of Law Lucie White’s Kitchen Table Conversations Project, Shivaram gained a valuable perspective into the lives of low-income women.

“I have become aware of this whole different world that a lot of people, especially a lot of men, don’t get to see,” he says.

He molded his firsthand knowledge into policy during a research internship last summer with the Institute for Women’s Policy Research in Washington, D.C. Meeting low-income Cambridge women through Kitchen Table Conversations, a series of informal conversations between Harvard students and local women coordinated by White, was a particularly instructive experience.

By getting to know a woman whose struggles were dominated by her obesity, Shivaram made a concrete link between poverty and a health issue such as obesity.

“It was fascinating to see the types of issues and problems that you don’t read about in books at all, yet which public policy could remedy, easily,” he says.

Yet the power structures of our democracy too often leave these women – and other groups – out of the debate.

“Going to D.C. to lobby with a senator or driving your car to the state capital or publishing an op-ed in the newspaper – you need some sort of means to get your voice out there, which these people don’t have,” he says.

After a year at Cambridge University in England on a Harvard-Cambridge Scholarship, Shivaram plans to attend Yale Law School, creating a solid foundation for what he hopes is a career in public policy.

As a male of South Indian origin, Shivaram is aware of the skepticism some civil rights and women’s groups may have of his involvement. Yet through hard work and integrity, he says, he’s won respect.

“You have to stay committed. It means that you’re the hardest-working member of the group. You practice what you preach. You want to guard against hypocrisy at all times,” he says.

While gender and ethnicity may distinguish him from other members of these groups, he forges connections with his empathy and his determination to help make their voices heard.

“[Their] courage really inspires me. I want to be a part of that and practice it myself,” he adds.

A privilege, a responsibility

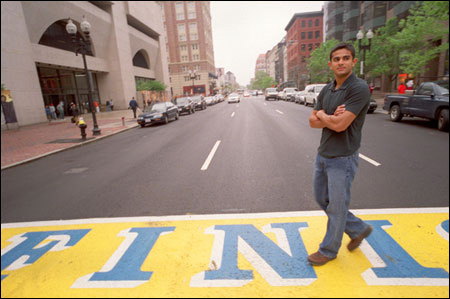

Shivaram approaches his extracurricular activities with the same zeal and dogged determination that characterize his academic and activist life. An avid runner since high school, he had a brief tenure on Harvard’s cross-country team before pointing his sneakers toward marathons. He’s completed five of the 26.2-mile foot feats, including three Boston Marathons. His best time in Boston’s competitive race was an impressive 2 hours, 52 minutes.

While training for a marathon can be every bit as demanding on one’s time as taking extra courses, Shivaram insists it’s time well spent.

“If I don’t run, I can’t do anything else,” he says. “And it’s a great way to enjoy the weather.”

Shivaram lists the Boston Marathon as one of his fondest Harvard memories. His others – living in Lowell House, eating in the dining hall, nurturing friendships with fellow students and tutors – are remarkably low-key for a student who clearly sets his bar high. Yet for this enthusiastic near-alumnus, such relationships and experiences have made his Harvard years unique.

“I really think that there’s no place like this in the world. It’s a privilege to be here, and that privilege is a responsibility, too,” he says.

Whether adding to his course load or advocating for those without voices, Shivaram is happy to shoulder that responsibility. “It’s a good thing,” he says. “It keeps you fighting, it keeps you motivated.”