This old house:

General’s historic homestead, long a puzzle for Harvard, has potential as teaching museum

Artemas Ward’s troubles began one April day in 1775 when he got out of bed, and they have continued now for more than 200 years. Ward’s two-century-old journey from pre-eminence to obscurity has provided lessons in historical research techniques for modern-day Harvard graduate students, lessons that they in turn have passed along to undergraduates.

Studying the rise and precipitous fading away of Revolutionary War Maj. Gen. Artemas Ward led graduate student Justin Florence to appreciate “the big questions” that historians must ask. Familiar tales, he has learned, sometimes fall apart when closely examined.

“Did this really happen, or is this just a dressed-up memory?” Florence asks. “How do we know it’s not propaganda? As a historian, the most important thing is to ask good questions.”

Two years ago, teaching that lesson to seven first-year graduate students was the goal of Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, the James Duncan Phillips Professor of Early American History and director of the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History.

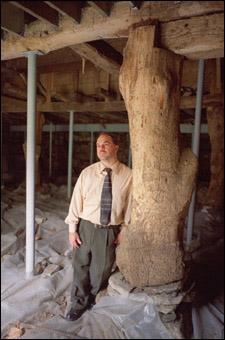

Ulrich took her students away from Cambridge, away from Harvard’s voluminous libraries and familiar museums, to Shrewsbury, to the nearly 300-year-old home of Artemas Ward. There, she instructed them to find a topic worthy of a major research paper.

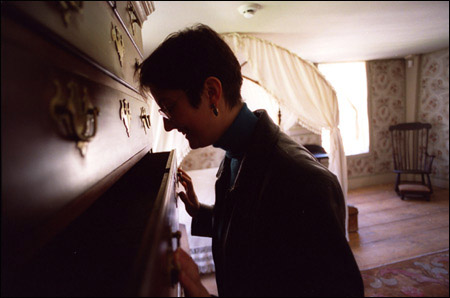

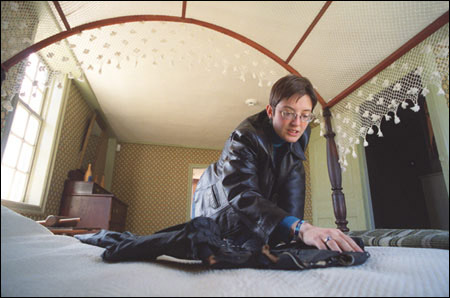

Graduate students Rebecca Goetz and Judy Kertész remember this was somewhat like being thrown into the deep end of the pool and told to swim. Though Ulrich was always available to support them, there are no velvet ropes, glass cases, or interpretive markers at the Ward house. Instead, there is a two-century accumulation of stuff, some of it decorously arranged, some squeezed into drawers, some stuck in corners or piled in the barn.

So students crept into the attic, opened trunks, rummaged in the basement. Seven different students found seven different research topics.

But first, they all considered: Who was Artemas Ward, and why does Harvard University own his house?

The rise, fall, and rise of Gen. Ward

April 19, 1775, was a fateful date for Artemas Ward – and for the 13 Colonies that would become the United States. Early that morning, British regulars and Colonial militiamen exchanged gunfire at Lexington and Concord; many were dead on both sides.

An express rider brought word to Shrewsbury, where Ward was sick in bed, suffering from bladder stones. Ward, a 1748 Harvard graduate, was a prosperous farmer, local judge, and provincial legislator; on Feb. 9, 1775, he had been reappointed second-in-command of the Colonial militia.

Despite his pain, the next morning Ward rode the 35 miles to Cambridge, where thousands of militiamen had gathered on Cambridge Common. The Massachusetts general who outranked him never showed up for duty because of age and illness, so Ward assumed command. This was a position he held for about 11 weeks, until a little-known Virginia planter named George Washington arrived in Cambridge on July 3.

Today, Washington is omnipresent, honored from the nation’s capital to the dollar bill. Ward, though he continued in public life until his death in 1800, has been all but forgotten. Even the town named for him in central Massachusetts changed its name in 1837 to “Auburn” to avoid confusion with the town of Ware.

Ward’s misfortune became Harvard’s good fortune. A Ward great-grandson, also named Artemas, made millions as a merchant and advertising executive by controlling advertising in the New York subways. In his later years, the great-grandson’s greatest wish was to have his ancestor recognized as an American hero.

To that end, in his will he gave Gen. Ward’s Shrewsbury homestead to Harvard, with a bequest of more than $5 million, “the income to be applied, among other things, to establish his reputation, too long neglected as a devoted and faithful friend of his country,” and to maintain the general’s home as a “public patriotic museum.”

That was in 1925. Harvard has never been quite sure what to do with the Ward bequest. In 1938, Harvard erected a statue of Gen. Ward in Washington, D.C.; the University also established a scholarship fund to help support an American history graduate student. Generations of Shrewsbury schoolchildren and the occasional Ward descendant have trooped through the house to pay their respects. Yet the house, 35 miles from Cambridge, is hardly known at Harvard, and those who do know it would never call it a first-rate museum. As grad student Rebecca Goetz quips, “It doesn’t even have a gift shop.”

The few who have been to the Ward house, though, recognize it as a unique scholarly resource, one with no parallel at any other research university. Soon after visiting the house, grad student Judy Kertész told some friends at other universities about the experience. “They couldn’t believe that this type of place still existed,” she said.

Goetz had a similar reaction. “It’s a window into a period that’s almost been untouched by the 20th century.” She can imagine not only history classes such as Ulrich’s using the homestead, but also courses in art conservation, decorative arts, and design.

The historians’ hunting trip

Kertész didn’t want to go. A Lumbee Indian, her interest is Native history. “I wasn’t thrilled about the assignment,” she recalled. What could a Colonial farmer like Artemas Ward, in Kertész’s estimation, “not charismatic, a bit of a fuddy-duddy,” teach her about Native culture?

“I was looking for Indians,” Kertész recalled. “I always see Indians in places where other people don’t.” And she found them at the Ward house, hidden in plain sight. A broom in the corner was made by Nipmucs, the general’s snowshoes were also of Indian manufacture. “Most people assume that historians are looking for documents,” Kertész said. “But if you don’t have written records, where do you go to find that history? You look at the material culture.”

Ulrich is an expert in understanding history through material culture; her book about the diary of a Maine woman named Martha Ballard, “A Midwife’s Tale,” won the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1991. In 2001, Ulrich’s book “The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth,” further explored what records of everyday occurrences could teach us about the past. Ulrich encouraged Kertész to explore; the graduate student wound up writing her paper based on “snowshoes, a broom, a name, and a drawing from a newspaper.”

The name was “Nahum,” Artemas Ward’s father, a biblical name that to Kertész indicates how the Ward family thought of themselves: as pioneers in a Promised Land, rather than as invaders in a land already settled by Native Americans.

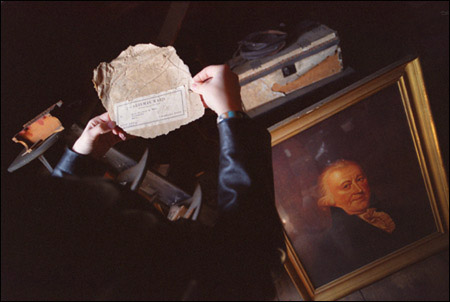

Kertész made her most dramatic discovery while prowling through the attic. The day was dark, and the house, with just two electric lights, was full of shadows. Kertész opened a trunk and discovered an old newspaper clipping: one of the general’s descendants, a land speculator in Kentucky, had discovered a mummified body in Mammoth Cave; a drawing showed how he displayed it for the public. Today, one would say he raided an Indian burial cave, but according to the ethos of the 1800s, he was an explorer discovering a relic of an ancient civilization.

Tying together such pieces allowed Kertész to understand a monumental issue – the displacement of Native Americans by English settlers – through the lens of one particular family. Though a sad story, the process was satisfying. “It’s absolutely a detective story,” Kertész said. “A good historian is a good detective.”

The Ward family also fascinated Rebecca Goetz, but she focused on the family’s fascination with itself.

She discovered among Ward’s descendants an amateur genealogist who wrote a well-received local history featuring the general, the colorful great-grandson who gave the Ward house to Harvard, and a bit of historical skulduggery.

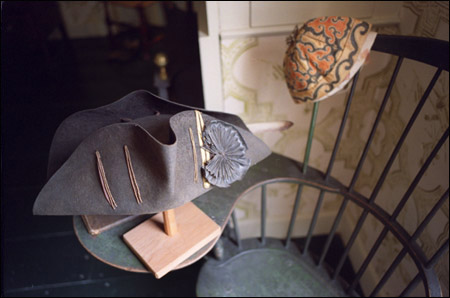

One room in the house is memorialized as that in which Gen. Ward died; his vest is laid out on his bed, his slippers are on the floor and the tricorner hat he wore as commander-in-chief is on a dresser. But the room is a fake, Goetz found: “He didn’t die in here,” she said. “It was a dairy.” Years ago the room was rigged for the benefit of visitors.

Such historical manipulations made Goetz question everything before her, such as the various biographies of Gen. Ward that proclaim him the “first commander-in-chief of the American Revolution.” It’s an inaccurate title, she thinks, since Ward’s commission as commander was from Massachusetts – though fellow grad student Justin Florence disagrees.

What about Washington?

Almost as illuminating for a historian as uncovering new information is differing with a past interpretation. Florence picked a big one to fight with: the ascendancy of George Washington.

On the Cambridge Common is a marker commemorating July 3, 1775, as the day that Washington, riding a white horse, assumed command of the Continental Army under what came to be called the Washington Elm. The undisciplined, ill-trained farmers trying to pass themselves off as an army rejoiced that finally they had a great leader.

The story is “part of the lore of the Revolution that every schoolchild learns,” Florence wrote. The problem is, it didn’t happen. Florence, for his paper in Ulrich’s class, read the diaries of average soldiers who, on July 3, were unaware, or unimpressed, that they were now under the command of the little-known planter. Washington was picked as commander in a political compromise designed to keep Virginia from leaving the coalition of rebellious Colonies; ordinary soldiers cared more about what they ate, what they sang in church, and who died in skirmishes with British regulars. “Nothing remarkable today,” wrote Samuel Hewes on July 3, expressing the sentiments of many of his fellow soldiers.

The idea that the soldiers were disorderly and ill-trained was first spread by Washington himself; later it was picked up, embellished, and repeated as part of building a national identity, Florence said. If the troops were not prepared to fight, that made Washington’s legend larger. But it also had the effect of diminishing Artemas Ward, making him unimportant, and ultimately forgettable.

The minor drama of Washington supplanting Ward has been playing itself out now for more than two centuries; Florence is trying to set the record straight without taking anything away from Washington.

Along with Goetz and Kertész, Florence is a teaching fellow in Ulrich’s undergraduate Core Curriculum course, “Inventing New England: History, Memory, and the Creation of a Regional Identity.” Florence’s charge to the undergraduates in his section – learn to ask good questions – is valuable whether one is considering Colonial America or the present. “To ask good questions about the Boston Massacre or the Battle of Lexington – Did this really happen, or is this just a dressed-up memory? – these are the same kinds of questions they should ask about what’s going on around them in the world today.”

Josh Cracraft, a graduating senior, was in Florence’s section. Cracraft – from Washington state – was surprised to learn that Washington’s assumption of command didn’t happen as it has been portrayed in history books. “This class on memory making has made me think differently than I have in any other class at Harvard,” he said. Cracraft is considering graduate school for American history.

The Artemas Ward house, long invisible to the Harvard community, is finally emerging from the shadows. Gen. Ward himself would be pleased. Two-hundred-and-twenty-eight years after he decided to get out of bed, it’s unlikely that his legacy will rest in peace. But at least he’s serving his country again.