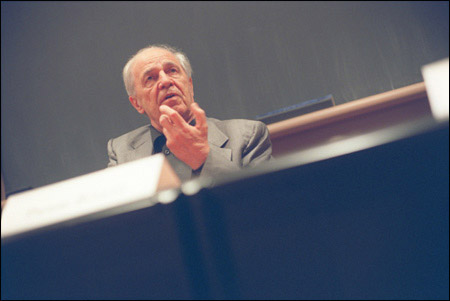

Master of 20th century music visits Harvard:

Pierre Boulez wows overflow crowd

Pierre Boulez, one of the great masters of 20th century music, was at Harvard last Friday (May 9), regaling an overflow crowd at the Center for European Studies with fascinating glimpses into his career as a composer and conductor.

Boulez spoke at an event titled “Pierre Boulez and French Modernism,” sponsored by the Music Department. The event began with a series of scholarly papers, followed by a discussion at which Boulez responded to questions posed by panel members. An evening discussion at Paine Hall titled “Boulez on Boulez” rounded out the program.

Boulez, along with composers such as John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen, dominated serious music in the post-World War II period. Known as an enfant terrible in the 1940s and ’50s, Boulez raised the hackles of artistic conservatives not only for the challenging nature of his compositions but for issuing provocative statements in which he repudiated the art of the past. He once wrote: “It is not enough to deface the Mona Lisa because that does not kill the Mona Lisa. All the art of the past must be destroyed.”

It was difficult to reconcile the image of that young firebrand with the genial 78-year-old who answered the panel’s inquiries with animation and Gallic charm, although he did make it clear that his attitude toward the past has changed little in the intervening years.

“I don’t believe in tradition at all,” he said. “Tradition is like the game where you whisper to your neighbor, ‘My handkerchief is in my left pocket,’ and after it goes around the circle it becomes, ‘The cat has eaten some chocolate.’”

Nor has age caused him to become any less critical of his musical forebears. Asked how he feels about recordings in which he has conducted his own compositions, he said that unlike Igor Stravinsky, he does not regard these efforts as in any way definitive.

“My recordings are just a photo of what I did at that time. Don’t take them any more seriously than they were meant.”

Recognizing that an artist is apt to feel proprietary about his creations, Boulez also refrains from advising others about how to interpret his music.

“When somebody else conducts my music I am like a backseat driver, which must be very obnoxious to the conductor. Therefore, I never interfere.”

Boulez spoke about his early years studying music in Paris during the German occupation. There was little cultural contact between France and Germany at this time, and for the young Boulez, German music ended with Wagner. After the war, Boulez and his contemporaries became caught up in a wave of cultural rediscovery.

“For people of my generation, it was quite interesting to discover artists of other cultures,” he said.

Among the German composers Boulez came to know was Arnold Schönberg, creator of the 12-tone or dodecaphonic method of composition. Boulez embraced the new technique, and his early compositions, such as “Polyphonie X” (1951) clearly reflect its influence. In his later compositions, like “Le marteau sans maître” (1952-54), and “Pli selon pli” (1957-62), he expanded on Schönberg’s approach. He also experimented with electronic music and, under the influence of Cage, explored the use of chance and indeterminacy.

As a conductor, Boulez has interpreted not only his own works and those of his contemporaries but those of earlier generations of composers including Stravinsky, Bartók, and Wagner. In 1971, he became principal conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic. In 1977, he returned to Paris to become director of the Institut de recherche et de coordination acoustique/musique (IRCAM), attached to the Pompidou Center (National Center for Contemporary Art). In 1995 he was appointed principal guest conductor of the Chicago Symphony.

Boulez has also recorded prolifically, and he had much to say about his approach to recording and about the difference between playing for an audience and playing in the recording studio.

“At a concert, time only goes forward, but with a recording, time goes forward and backward, and therefore you have to be clean, no defect. You have your screwdriver, and if something goes wrong you can fix it. But at the same time you want life. If there are too many corrections, it becomes artificial. Therefore I try to record as long stretches as possible to try to keep the trajectory of the music.”

Boulez spoke of the advantages of knowing a piece of music thoroughly. He said that the more times a conductor performs a piece, the more intuitive he can become. And yet the conductor must avoid a mechanical repetition of the performance.

“For me the worst thing is when you repeat the same thing 10 or 15 times until you can’t stand it anymore. Then you might as well be just selling bananas.”

Next year at the music festival in Lucerne, Switzerland, Boulez will share his experience as a conductor and composer with younger artists. He will conduct an orchestra composed of young performers who will play compositions by young composers in a workshop setting. The aim will be to create a dialogue between composer, conductor, and orchestra, resulting in a greater realization of the piece. The finished pieces will be presented in a concert the following year.

Boulez himself, though hardly a beginning composer, plans to submit new work for the young musicians to play and critique.

“I must show by example,” he said. “If I never present new compositions myself, no one else will want to do it.”