Fascinating site, mystifying language:

Richard Meadow talks about recalcitrant site of Harappa

The ancient Egyptians carved the revered names of pharaohs in larger-than-life-size letters across their imposing pyramids. In the Royal Tombs of Ur, the Mesopotamians etched stretches of hieroglyphic-esque characters that offer evidence of their ideologies and daily regimens. But the ancient Indus people of Harappa left less comprehensible clues about themselves and therefore remain far more mysterious to modern scholars and National Geographic junkies alike. Ancient Harappa was one of the world’s first cities. This metropolis along the Ravi River, now modern Pakistan, was flourishing as its more familiar ancient neighbors were making Bronze Age advancements.

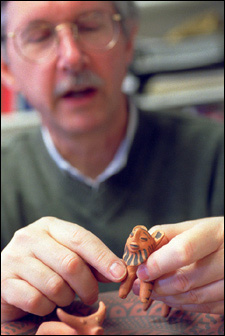

Harappa has been the subject of intensive scrutiny for a select set of experts involved in the Pakistani-American Harappa Archaeological Research Project (HARP). The team, which includes paleoethnobotanists and specialists in animal bones, plants and ancient technology, works under the leadership of Richard H. Meadow, who gave a standing-room-only talk at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology last Thursday (April 24).

“[The project is] changing how we understand the nature of the site, our vision of the growth, development, and de-urbanization of Harappa,” said Meadow, a senior lecturer on anthropology and director of the Zooarchaeology Lab at the Peabody Museum.

In the hour that he spoke, Meadow showed slides that covered the history of Harappa, which spans from roughly 3300 to 1300 B.C., reaching its peak around 2500 B.C.; the history of the archaeological exploration of the city, which began in the late 1800s; Harappan feats of civil engineering that have been uncovered; evidence that the city had ties – mercantile and otherwise – with regions in Afghanistan and Central Asia; and the science of sediment, or how layers of dust, debris, salt, and sand contribute to the preservation or erosion of hulking structures and minute relics.

But the most pressing issue – one that emerged as the recurring theme in Meadow’s talk – is the puzzling script of this agriculture-based society. Few clues exists to help researchers decipher the meaning of the characters, which are hieroglyphiclike in appearance, and remarkably consistent throughout the five periods in which Harappan civilization progressed.

“We have a foundation of material culture that continues to manifest through the late period. There are beginnings of forms on ceramics that later became script . . . Trash which is dumped is a treasure trove for archaeologists. In trash deposits we’ve found evidence of writing in the Kot Diji Phase (2800-2600 B.C.) that has continuity at Harappa into the [later periods],” said Meadow.

There had been single-season investigations of Harappa in 1946 and 1966, but HARP marks the first time since 1942 that any enduring enterprise has been undertaken on the site. HARP’s early beginnings date to 1986 when George Dales of the University of California, Berkeley, set up the camp. After Dales’ death in 1992, Meadow took over as director with Mark Kenoyer, a student of Dales who is based at the University of Wisconsin.

The excavation is safeguarded by the Department of Archaeological Museums, a division of Pakistan’s federal government responsible for protecting sites of major cultural significance. Meadow spoke of the help, goodwill, and support the department offers that “makes the work that much easier.” The protection also makes this excavation unique in that everything unearthed is kept at the site.

Archaeology is generally recognized as a field that crosses bridges among disciplines, weaving history, social sciences, and natural sciences together to understand the ways of life of other people. But in this case, HARP itself bridges two modern cultures. Meadow said a number of Pakistanis have become involved with HARP in various capacities. The team trains colleagues in the country to help document and map all the findings in a database, and area residents assist at the site with excavating, cleaning objects, and general activities, from cooking to financing.

But despite the enormous amount of labor and talent at work on the site, many of its puzzles persist.

“Unraveling the history of an ancient city is a huge challenge, especially when the baked bricks are stolen,” said Meadow, explaining that much of Harappa’s structures were built with a combination of baked and unfired bricks. In the late 1800s, the British stole baked bricks to make ballasts for the railway they were constructing in Pakistan. The rest were left intact, which makes excavating an exercise in strategic planning.

Much digging is still needed to solve the many mysteries that remain. “Three portions of the ancient city were surrounded by perimeter walls that served – what function?” Meadow asked, citing just one of the new questions raised by new findings. Like many of Harappa’s ambiguities, this one has various possible answers. The tremendous, impassive walls may have served as protection from flooding from the nearby Ravi River, as a retaining wall to help secure the city as it was built up, or as defense – though there’s no clear evidence of warfare or violence.

“[HARP] is the only modern excavation under way at an Indus site. It’s the only project that has any hope of improving our understanding of Indus civilization. It’s probably the only new data we’ll get,” said Bryan Wells, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Anthropology. Such new data is especially valuable to him as he works on his dissertation about the cryptic ancient script.