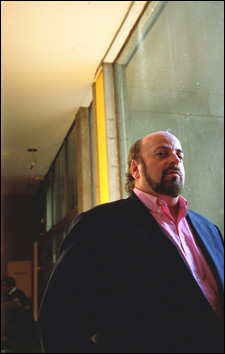

Toback: ‘Harvard Man’ for a day

Filmmaker James Toback ’66 was at the Harvard Film Archive last Friday (April 18) for the screening of his 1978 film “Fingers.”

The film, long a cult classic, is coming out in DVD this month, with extra features that include commentary by writer/director Toback and an onscreen conversation between Toback and the film’s star, Harvey Keitel. Toback said he was delighted the film is appearing in the new format.

“It’s a matter of availability,” he said. “Coming out in DVD gives it a second life.”

Toback’s other films include “Love and Money” (1982), “Exposed” (1983), “The Pick-up Artist” (1987), “Two Girls and a Guy” (1997), “Black and White” (1999), and “Harvard Man” (2001). He also wrote the screenplay for “Bugsy” (1991).

“Fingers,” the story of a violent mob enforcer who aspires to be a concert pianist, was Toback’s first film as a director. In an interview before the screening, he talked about his oblique route from Harvard undergraduate to filmmaker and some of the lessons he learned along the way.

As an English concentrator at Harvard, Toback knew he was an artist. “But I was an artist without portfolio. I was an artist without an art.”

While Toback failed to discover his life direction during his student years, he did discover many other things.

“I thought of Harvard as a way of exploring different worlds. It’s the greatest university because it’s a microcosm of the planet. If you explore the University thoroughly, you expose yourself to every imaginable kind of life.”

While searching for his métier, he taught at City College in New York and wrote short stories and magazine articles on the side. An assignment to interview Jim Brown led to a friendship with the football-great-turned-actor, a relationship that Toback wrote about in his book “Jim: The Author’s Self-Centered Memoir of the Great Jim Brown.”

Toback’s first screenplay was “The Shades Below,” which he wrote with Jacob Brackman ’65, a former colleague on the staff of the Harvard Advocate. The script was never produced, but it did give Toback confidence to try another one on his own. This was “The Gambler,” released in 1974, and starring James Caan.

Toback based the script on his own experiences as an addictive gambler, a psychological malady that he says bears little resemblance to the mental state of the recreational gambler or the professional who gambles for money.

“When you do it to flip your life upside down and turn it over to a force you have no control over, it becomes a whole different phenomenon. It makes no sense to a non-gambler. The normal mind just doesn’t see the point.”

“The Gambler” was directed by Czech-British director Karel Reisz, who liked Toback’s script, but was unfamiliar with the world it portrayed. Toback went to London and spent a year of preproduction time coaching Reisz on the background of his film and in turn learning the art of filmmaking by watching the director at work.

“I used the experience of being with him on the set as my film school. By the time ‘The Gambler’ was done, I was ready to make movies.”

The movie on which he lavished his newly acquired skills was “Fingers,” which, in addition to Keitel, stars Jim Brown as the violent Dreems and Tisa Farrow as the female lead, Carol.

“I found Tisa Farrow driving a cab in New York,” Toback said. “I looked in the rearview mirror and said, ‘Your eyes are the eyes of my leading lady.’ She said, ‘You don’t want me. You want my sister.’ I said, ‘Who’s your sister?’ She said, ‘Mia Farrow.’ I said, ‘No, I don’t want her. I want you.’”

The film was shot in 19 days, an experience Toback describes as dark and intense.

“We knew we were doing something from the darkest, deepest part of our souls. No other movie of mine hits a nerve quite the way ‘Fingers’ does.”

The movie’s intensity and violence had a visceral effect on many first-time viewers.

“It was reviled by 80 percent of the people who saw it. People screamed at the screen. They got up and walked out.”

Toback said that neither eliciting that reaction nor avoiding it were ever part of his thinking when he made the film.

“I make movies in a very unmanipulative way. I intentionally try not to think of the effect a scene will have. Instead, I ask myself what the reality of the character would be, what would happen next.”

No one screamed or walked out of the screening Friday night, which may mean that this provocative filmmaker may perhaps be gaining the acceptance that eluded him 25 years ago.