Symposium analyzes, celebrates ‘thug’:

Legendary Tupac Shakur looked at as cultural artifact, force

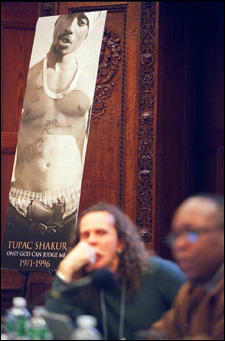

Few spaces at Harvard are more burdened by symbols of the University’s glorious past than the Barker Center’s Thompson Room.

While the room itself is not particularly large, everything in it is on a grand scale, from the towering grandfather clock to the walk-in stone fireplace topped by a bust of John Harvard, both prominently inscribed with Veritas shields. Standing portraits of Theodore Roosevelt, Percival Lowell, and other Harvard notables hang from the floor-to-ceiling oak paneling, in which names such as Emerson, Longfellow, Bulfinch, and Agassiz have been carved in bas-relief.

But for one day last week (April 17), these dignified totems of authority and rectitude were all but effaced by portraits of a young black man, his head shaved, his muscular arms and torso heavily tattooed, and his heavy-lidded eyes conveying an expression both menacing and soulful. In several photos he brandished a handgun, and in one he wore a large automatic tucked into the waistband of his boxer shorts.

The occasion was an academic symposium titled “All Eyez on Me: Tupac Shakur and the Search for the Modern Folk Hero.” It was co-sponsored by the Hiphop Archive, the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research, the Program of Folklore and Mythology, and IKS University of Oslo, Norway.

Shakur, a rapper and film actor, died in 1996 at the age of 25, the victim of a drive-by shooting outside a hotel in Las Vegas. Like James Dean and Elvis Presley before him, he is believed by many of his fans to have faked his death and to be living secretly somewhere, perhaps Cuba.

If anything, his devotees have grown more numerous and adoring since his demise. Tupac Web sites abound, offering discussion groups, downloadable recordings, photos, and forums for conspiracy theorists. Dozens of books have been published about the rapper, ranging from popular biographies to speculations about his death to scholarly interpretations of his music and his significance as an icon of popular culture.

Mark Anthony Neal, an English professor from the State University of New York, Albany, gave a talk titled “Thug Nigga Intellectual: Tupac as Celebrity Gramscian,” in which he argued that Shakur could be seen as an example of the “organic intellectual” who expresses the concerns of his group, a concept articulated by Antonio Gramsci, the Marxist political theorist.

Murray Forman, a professor of communications studies at Northeastern University, discussed the “Tupac lives” theory in its myriad manifestations, a task that must have required hundreds of hours surfing through Tupac sites on the Internet.

“Tupac’s murder provided a catalyst for his re-emergence in digital form,” Forman said. “His fans have succeeded in resurrecting Tupac as an ethereal life force.”

Knut Aukrust, a professor of culture studies at the University of Oslo and a visiting scholar in the Program on Folklore and Mythology at Harvard, described his first exposure to Shakur’s music while driving to Florence, Italy, to conduct research on the Renaissance writer Niccolo Machiavelli – an odd coincidence, he proposed, since Shakur renamed himself “Makavelli” on one of his albums.

In a similarly open-ended way, Aukrust pointed out that Shakur’s birthday, June 16, coincides with Bloomsday, the fictional 24-hour period that forms the time frame for James Joyce’s “Ulysses.”

Reaching for suggestive parallels between Shakur and literary figures of the past or applying the ideas of theorists like Gramsci and Mikhael Bakhtin to the rapper’s output were symptomatic of the difficulty all the presenters seemed to have with finding a suitable approach to this undeniably fascinating artist. While it seemed impossible to fit Shakur into a neat framework, all agreed that his music as well as his tumultuous life justified the effort of scholarly inquiry.

Tupac’s mother, Afeni Shakur, was a prominent member of the Black Panther party, but later became addicted to crack cocaine. A high school dropout, Shakur read widely, familiarizing himself with the work of many contemporary social theorists, a fact that has surprised many who know him only as a rapper. Others are offended by that surprise.

“How do we end up thinking that Tupac didn’t read books?” asked Marcyliena Morgan, director of the Hiphop Archive. “What is that assumption? And then why do we think, ‘Oh, he read that. So did I. Isn’t he special?’”

“I think reading those books is impressive for anyone of that age,” replied Forman.

One member of the audience asked the panelists what they had to say about the glorification of violence and abuse of women in Shakur’s lyrics.

“Well, he’s a walking contradiction,” Neal said. “But because of that, he makes the process of being an intellectual accessible to ordinary people.”

Emmett Price, an ethnomusicologist from Northeastern, traced the evolution of trickster figures in African-American folk tales to the urban badman of the post-slavery period, an archetype to which Shakur’s public persona conforms.

And yet he was more than that, Price asserted, characterizing Shakur as a prolific artist driven by a terrible sense of urgency who struggled to unify mind, body, and spirit.

“He was also very similar to the rest of us – a work in progress.”

Greg Dimitriadis from the University of Buffalo’s Graduate School of Education spoke about his interviews with young fans of Shakur and their beliefs about the rapper and his death. These ranged from blind faith (“Tupac’s not dead, ’cause I just know.”) to anger and a feeling of abandonment because of Shakur’s failure to reveal himself and confirm the fact of his survival.

Cheryl Keyes, an ethnomusicologist from the University of California, Los Angeles, said that Shakur’s life “reflects living on the edge. His life wasn’t very different from those of other black men. It was just that he lived his in the public spotlight.”

But the guy who blew everyone away was the keynote speaker Michael Eric Dyson, Avalon Professor in the Humanities and African American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and author of “Holler If You Hear Me: Searching for Tupac Shakur”(BasicCivitas Books, 2001). Speaking in an intense, cadenced, crescendoing style that clearly derived from black preaching, Dyson combined the vocabulary of post-structuralist theory with the language of the streets while quoting liberally from Tupac, Notorious B.I.G., Snoop Dog, Nas, and Mos Def.

Dyson, who has written books on Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, as well as issues in contemporary culture and race relations, said that when colleagues heard he was writing a book on Tupac Shakur, they asked “Why would you waste time and energy writing about this thug?”

Dyson’s answer was that “Tupac spoke to me with brilliance and insight as someone who bears witness to the pain of those who would never have his platform. He told the truth, even as he struggled with the fragments of his identity.”

Although Shakur was “deeply and profoundly self-destructive” and that in looking at his life, “you can see his rush toward the grave,” it is important to note that “the heroic character of Tupac was not predicated upon his moral perfection.”

A reader of theologians like Teilhard de Chardin, Shakur was obsessed by the problem of evil, Dyson said, and through his music, “got at the heart of the hurt and suffering that was going on in human society and gave it a voice.”

Hearing Dyson’s words, one wondered whether the heroes of Harvard’s past whose images adorned the Thompson Room’s walls were convinced of the heroism of this thug poet. But on further reflection, one found resolution in the thought that in the world of shades, perhaps superficial differences held less importance than we in the living world suppose.