Popular music that belongs to everyone:

Doctoral candidate has idea for egalitarian licensing

In his 1970s lament for lost innocence, “American Pie,” Don McLean sang about “the day the music died.”

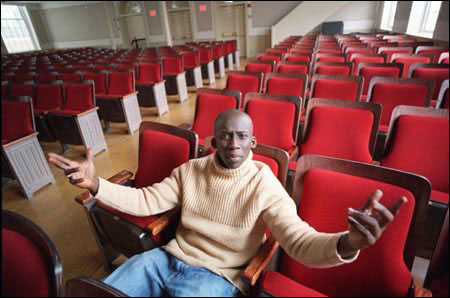

Derrick Ashong ’97, definitely more of a glass-half-full sort of guy, is looking forward to popular music’s rebirth, and hopes to perform midwife duties at the blessed event.

Ashong, a Ph.D. student in Afro-American Studies and Ethnomusicology, is also CEO of ASAFO Productions, a talent agency that represents new, up-and-coming musical performers – like the funk/harmony/R&B group Ashong himself sings with, Soulfège.

But ASAFO Productions does more than simply represent its clients. It offers them a new way of getting their music out to the public that just might revolutionize the music industry.

ASAFO’s secret weapon is a new way of licensing music called the FAM License, an acronym standing for “Freedom, Access, Music.”

“We wanted those ideas to be the three cornerstones of our business,” said Ashong. “But it also stands for family, because we think of ourselves as kind of a family.”

The terms of the license are so liberal, they might be summed up as “steal this song.” But there is more to the idea than just anarchic generosity.

The license allows anyone to copy and distribute the music commercially or noncommercially in a modified or unmodified form. The only stipulation is that the artistic credits for the original composition must accompany all subsequent copies.

But why would musicians want to give their music away? The answer is simple: exposure.

“For independent artists, it’s very hard to get their music out there. There are only five major record labels – Universal, Sony, EMI, Warner, and BMG – and they have such high overhead costs that they can’t take a risk on artists who appeal to niche markets.”

Even if artists have the good fortune to sign a recording contract with one of the big companies, there’s no guarantee that their CD will make money. Recording companies customarily recoup production and promotional costs before paying artists their share of the profits. According to Ashong, it’s possible for an artist to sell half a million copies of a CD and still not make any money.

“But what if you could get a bunch of people promoting your music? What if you could say to them, ‘Here’s my music, here’s what you can do with it?’”

What people can do with music licensed under FAM is basically pass it around – download it from the Internet, burn it on CDs, send it to radio disc jockeys, music promoters, and friends around the world. According to Ashong, who was born in Ghana and spent much of his childhood in the Middle East, ASAFO Productions can help with this process through the growing international network it has developed.

“Because I’m from a developing country, I’m particularly interested in reaching audiences around the globe and finding ways for people to share music as equals,” he said.

And yet, Ashong insists, the FAM license does not prevent musicians from making money from their music. They can still sell CDs themselves, a far more profitable way of marketing their music than signing with a big company. They can also perform live, which is how most musicians make the greatest portion of their income, and because of the wider notoriety the FAM license will gain for them, the offers for gigs should come in greater quantities.

And because the FAM license only licenses recorded music, not songs, songwriters will still be able to profit from their work if their compositions become popular.

While the FAM license has yet to be proven effective in the real world, it is based on a model that already has been highly successful in its own field – the free software movement. Free software is not necessarily free in the economic sense, but can be freely copied, altered, and improved upon by its users.

This strategy of giving all users free access to the source code on which a piece of software is based, enabling them to adapt, expand, and improve the original product, has come to be known as “copyleft,” to distinguish it from the traditional and more restrictive practice of copyright.

The free software movement has been active for about 20 years and has been responsible for several notable successes. For example, the Apache Webserver, developed by the Apache Software Foundation, now commands almost 65 percent of the market, having been adopted by such companies as Yahoo and eBay.

Recognizing the value of organizations like Apache, large computer companies such as Apple and IBM are supporting their work with development grants.

In designing the FAM license, Ashong and his colleagues consulted with some of the pioneers in the free software field and are convinced that the music industry, which has been losing money for the last few years, is in need of a similar approach.

“There’s no working model right now for artists to get paid for what they do,” said David Brunton ’97, a partner in a Washington, D.C.-based software development firm, Plusthree, as well as a partner in ASAFO. “The only model is one that allows five record labels to barely stay afloat.”

In the three and a half years ASAFO Productions has been in existence, all those involved have learned a tremendous amount about the music industry, how it operates, and most important of all, what happens next. Brunton isn’t quite willing to predict the future, but he believes that the FAM License concept has a good chance of being part of it.

“It’s an unproven model in the recording industry, but it’s worked phenomenally well in the software industry. If it eclipses the mainstream model or just remains an alternative, it will still be a great success.”

As for those listeners who may be enjoying music without paying for it, that, he believes, should be the least of an artist’s worries.

“The artists’ biggest nightmare should never be that the public is making copies of their music and listening to it. That should be their dream.”