Perception, reality differ vis-à-vis children’s health risks:

Symposium works to reduce risks to kids

In a survey of attitudes toward risks for children, respondents cite drugs and sexual abuse among the top 10. They’re not.

On the other hand, only a small proportion of respondents cite poverty as the top 10 risk to children that it is.

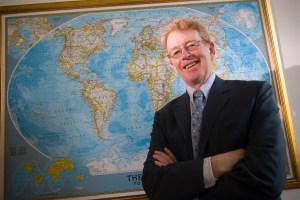

The difference between perception and reality as it concerns children’s health and safety is a serious roadblock to efforts to reduce risks, the director of the Harvard Kids Risk Project said March 26. In order to get the public to act on significant risks, it needs first to understand them, according to Kids Risk Project Director Kimberly Thompson, an assistant professor of risk analysis and decision science at the School of Public Health.

Thompson and the project organized a two-day symposium in an effort to engage members of the business, nonprofit, academic, and other communities to work to reduce risks to children’s health.

Held at Memorial Hall’s Annenberg Hall, the symposium, called “Managing Children’s Risks: It Takes a Commitment,” drew more than 100 participants. Thompson said the goal was to reach as broad an audience as possible.

The two-day event included speeches and panel discussions on topics ranging from the impact of the media on children’s health to vaccines, nutrition, and the importance of corporate leadership.

School of Public Health Dean Barry Bloom kicked off the symposium, saying that in these days of turmoil, the problems of children around the world warrant our attention.

“This is a difficult time. There are kids all over the planet suffering, and suffering in horrible ways,” Bloom said. “I think there are few subjects more worthy of our serious thought, particularly at this time, than risks to children.”

Thompson set the tone for the two-day event by highlighting new data and some new research on risks to children.

Poverty is a large risk, with 16 percent of children under age 18 living below the poverty line and 4 percent living in conditions of moderate to severe hunger.

The number of children living in two-parent families has declined, to 69 percent from 77 percent in 1980. U.S. teen pregnancy rates are among the highest in the developed world, with 26 out of every 1,000 girls age 15 to 17 becoming pregnant.

Education is another trouble spot, with 14 percent of the nation’s 18- to 24-year-olds not finishing high school and 8 percent of teens age 16 to 19 neither in school or working.

Substance abuse continues to be a problem, with one survey showing 30 percent of high school seniors having had five drinks in a row at least once in the previous two weeks. One quarter of the seniors reported using illegal drugs in the previous 30 days, and 21 percent said they smoke cigarettes daily.

“There are some very big challenges kids are facing today,” Thompson said.

Statistics on annual child mortality flesh out the picture of risks to children a bit more. The statistics, also presented by Thompson, show that accidental death is the major cause of death for children under age 10.

Motor vehicles account for the largest number, 50 deaths per million children under age 10. Drownings account for 21 deaths per million children, fire 19 deaths per million, while suffocation accounts for 18 deaths per million.

Accidents involving toys, which have been prominent in the national spotlight, was far down on the list, claiming 0.4 lives per million children.

While accidental deaths combine to create the most common cause of death for children under 10, homicide was the second-highest single cause, resulting in 24 deaths per million. Thompson said the number of gun-related deaths, which account for just 5 in the under-10 age group, rises quickly as the age of the child increases.

“[The homicide statistics] tells us how poorly we’re doing in child protection and child abuse,” Thompson said.

Thompson released two studies to coincide with the symposium. In the first, published online at Medscape.com, she showed that there doesn’t appear to be a link between the increase in infant bathtub drownings and the increased use of infant bath seats, as some have suspected. In fact, her analysis showed, the seats may actually slightly decrease bathtub drownings.

The increased presence of bath seats in cases where children have drowned, she said, reflects increased sales of the seats since they were introduced in the early 1990s. With more seats on the market, she said, it is more likely they will be in use in a tub when a baby drowns. There does not appear to be a link between the seats and drownings, however, she said, as the overall rate of drownings has declined slightly.

Her results, she said, shows that while it is easy to blame new technology, like the bathtub seats, it’s important to keep attention focused on broader root causes, like the inattention of caregivers.

“The focus on bath seats takes attention from the underlying cause of death, which is that too many caretakers are leaving infants unattended in bathtubs,” Thompson said.

The second study, also published on Medscape.com, was a survey of America’s largest companies to evaluate their commitment to children’s health. The survey was intended to show what corporate resources are currently spent on children to help craft strategies for future efforts. The survey found that about a third of the 333 Fortune 1000 companies that responded have vision statements, mission statements, or guiding principles that include a commitment to children. That commitment is expressed in different ways, the survey found, from employing children under age 18 to contributing to organizations that work to improve child welfare.

Reducing risks to children requires a multifaceted effort, involving people from many different aspects of society, Thompson said. Getting accurate information about the risks that children face is critical, as is repeatedly communicating those risks to parents and other caregivers.

“I hope that by having a broad range of people … represented we’ll be working toward a future where we will work better together,” Thompson said.