Next step: Daunting task of rebuilding:

Sandy Berger talks at Law School about difficult tasks ahead in Middle East

Rebuilding Iraq after Saddam Hussein is defeated will be a job of enormous magnitude and one for which Americans have not been adequately prepared.

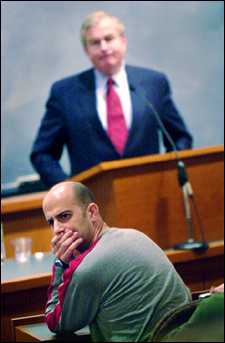

This was one of the major points made by former National Security Adviser Samuel (Sandy) Berger in a talk Thursday (March 13) at Harvard Law School. Berger’s topic was “Iraq, Terrorism and North Korea.” A 1971 graduate of the Law School, Berger served as national security adviser to President Bill Clinton from 1997 to 2001.

“I don’t think Americans have been exposed to how formidable that effort will be. Think about the postwar effort in Germany and Japan – that’s what it’s going to be like.”

According to Berger, the tasks U.S. authorities will face in a postwar Iraq include ensuring the nation’s territorial integrity, managing potential conflict between Kurds and Turks in northern Iraq, finding Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction, administering food to 14 million Iraqis now being served under the United Nation’s oil for food program, managing an enormous refugee problem, dealing with the 350,000 members of the Iraqi army, and ensuring the continuation of vital services now being handled by Hussein loyalists.

Moreover, these tasks must be accomplished despite resistance both from the Arab world and from within our own forces.

“The Arabs will want us out as soon as possible. The American military doesn’t like it. They’re trained to fight wars, not to be policemen.”

Berger said that threats confronting the United States are four: the war in Iraq, the threat of terrorism, the threat of North Korea, and the crisis of confidence in American leadership.

Regarding Iraq, Berger said it was imperative to disarm Hussein, but that the need was not so urgent that the United States must act without international support.

“The prospect of Saddam with nuclear weapons is very disturbing,” Berger said. “I think he believes that we will not move against him if he has them. What he wants, judging from his past actions, is to dominate the region. Strategically, this would be unacceptable to us because if we fail to disarm him, a nuclear Saddam will assume he has the green light to proceed with his plans of territorial domination.”

Berger advised against invading Iraq with only British support.

“If we invade as an American-British enterprise, all the risks are greater – the risk that Saddam’s loyalists will stand and fight rather than collapse, that the war will create turmoil in the region, that there will be an anti-American backlash around the world. I don’t think we can let Iraq ‘rope-a-dope’ us forever, but I believe there is a right and a wrong way of going about it.”

Berger said that if the international community established a series of deadlines backed up with military force, Hussein would probably be forced to disarm.

But such efforts at coalition building will require skilled and coordinated diplomacy, and Berger was critical of the heavy-handed way in which the Bush administration dealt with its allies.

“You know what the Bush version of diplomacy is? ‘Let me tell you what our position is. You don’t agree with me? Let me tell you again. You still don’t agree with me? Let me tell you louder.’”

While we are fighting Iraq, it is imperative that we not lose our focus in the war against terrorism, Berger said. This will be difficult because war tends to absorb the complete attention of the top levels of government, a lesson Berger learned during the United States’ bombing of Kosovo. He said that so far, our homeland security efforts have been overly concentrated on air travel.

“We’ve thrown $35 billion at the airports. The airports are the only thing that’s secure. If you were a terrorist and you tried to infiltrate the airports now, you’d have to have an IQ of about 50. But less than 2 percent of the cargo containers in our harbors are being inspected.”

The problem posed by North Korea must be dealt with concurrently with the Iraqi situation, Berger said. He questioned the administration’s priorities regarding these issues.

“I’m mystified why we don’t sit down with the North Koreans now, before the war starts, and try to freeze the situation so we don’t have to worry about it while the war is going on. The administration says we’ll deal with North Korea after we deal with Iraq. I think it should be the other way around.”

Berger was also critical of the administration’s handling of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

“These two parties are caught in a death grip,” he said. “They are unable to change the situation by themselves. There have always been two pillars to our policy. On the one hand, we’ve been Israel’s strongest ally. And on the other hand we’ve tried to bridge the gaps between them and their enemies. In the last two years, this second leg has fallen off.”

But despite the overwhelming challenges the United States now faces, Berger said that it is still possible for the situation to turn out for the best.

“I’m not a pessimist and I’m not a fatalist. We must bear in mind that our history is replete with situations in which we have faced extraordinary challenges. The American Revolution could very easily have been lost and all the Founding Fathers might have ended up being hanged for treason. We’ve been through the Civil War; we fought the Nazis in World War II. If we keep our heads, we can negotiate our way through these troubled waters and build a more secure and safer world.”