‘Engaged Buddhists’ take on world:

Religious movement is a global phenomenon, taking many different forms

To some, “engaged Buddhism” may seem like a contradiction in terms. Traditionally, Buddhists have sought to avoid suffering by disengaging from desire, training themselves through meditation to look past the world of illusion to the spiritual reality beneath.

But during the past few decades Buddhists have been re-examining the teachings of their religion and finding a basis for social action, for confronting war, racism, exploitation, commercialism, and the destruction of the environment.

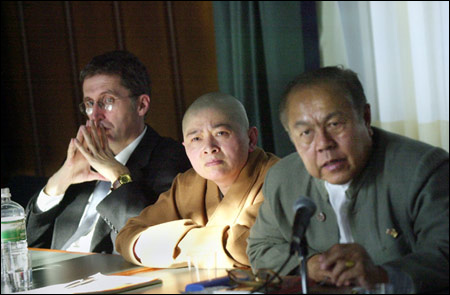

One of the world’s leading engaged Buddhists, Sulak Sivaraksa, currently a fellow of the Harvard Yenching Institute, spoke March 14 in a symposium called “Buddhism, Globalization, and Social Change.” Also on the panel were Venerable Yifa, a Taiwanese Buddhist nun and director of the Greater Boston Buddhist Cultural Center; Charles Hallisey, associate professor of Buddhist studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison; and Janet Gyatso, the Hershey Professor of Buddhist Studies at Harvard. Christopher Queen, lecturer on the Study of Religion, was moderator.

“There’s been a sea-change in the Buddhist tradition,” said Queen, who has edited several books on engaged Buddhism. “Buddhists have gotten up off their cushions, recognizing that collective sources of suffering in the world must be addressed by collective action.”

Engaged Buddhism is a global phenomenon, taking many different forms, said Queen. Prominent members of the movement include B.R. Ambedkkar, who brought Buddhism to the “untouchables” of India; Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Zen master, known for his activism against the war in Vietnam; and A.T. Ariyaratne, founder of the Sarvodaya Shramadana rural development movement in Sri Lanka.

Sulak, the founder of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists, is Thailand’s leading dissident and public intellectual. The author of many books and articles, he has been jailed and exiled several times by Thai authorities for speaking out about state policies on environmental justice and human rights. He has been twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and in 1995 received the Right Livelihood Prize from the Swedish Parliament.

In his talk, Sulak spoke about nonviolence as the master precept of Buddhism and discussed the ways in which Buddhism’s other precepts are related to this master teaching.

For example, he said, Buddhism forbids stealing. “But if you let a few collect wealth at the expense of the poor, that is worse than stealing.”

Similarly, Buddhist teachings condemn sexual misconduct. Yet in Thailand today, where many young women are forced or tricked into lives of prostitution from which they find it difficult to escape, the responsibility for this activity falls on those who organize and profit from the sex trade, not on its powerless victims.

“We must interpret the precepts in a modern way,” Sulak said.

Yifa, who earned a law degree from the National Taiwan University and a Ph.D. in religious studies from Yale University, has been a nun at Fo Guang Shan Monastery in Taiwan since 1979. She has been an administrator at Fo Guang Shan Buddhist College and at Hsi Lai University, Rosemead, Calif., a visiting scholar at the University of California at Berkeley, and a faculty member at National Sun Yat-Sen University.

In her talk, she discussed the establishment and subsequent decline of women’s monastic orders in Buddhism. Only in China did these orders persist, and today only in Taiwan can they be said to flourish.

Yifa faced opposition from her middle-class family when she announced her intention to enter Fo Guang Shan Monastery in Taiwan. Her current research focuses on women in Buddhism. Her book on monastic rules and institutions, “The Origin of Buddhist Monastic Codes in China” (Hawaii University Press, 2002), discusses all aspects of life in Buddhist monasteries during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.).

Hallisey described his students’ adverse reaction when Sulak came as a guest lecturer to one of his classes and spoke on the Buddhist view of democracy. Westerners, and especially Americans, believe they invented democracy, and find it difficult to hear a person from a different culture criticize their beliefs and practices, he said.

The Western view of democracy emphasizes the freedom to acquire- the right of citizens to obtain justice under the law, economic opportunity, the ability to speak freely, etc. But Buddhists are more likely to stress the freedom to give, characterized by “generosity on one person’s part toward another, the ability to give others the freedom to be themselves.”

From this viewpoint, introspection is of paramount importance in a democratic society. “We must look into ourselves and see if there is democracy in our hearts,” Hallisey said.

Gyatso’s talk focused on the question of women’s monastic orders in Buddhism, taking up the issues that Yifa had raised, but from a more scholarly perspective. She discussed Buddha’s acceptance of women in monastic orders, but only if they were governed by “the Eight Heavy Rules,” which make the most senior nun subordinate to the most junior monk.

“That is the situation Buddhism faces today- how to handle challenges to authority brought by the feminist critique. Just as we haven’t attained full democracy, we also have not attained gender equality,” she said.