Abolish prisons, says Angela Davis:

Questions the efficacy, morality of incarceration

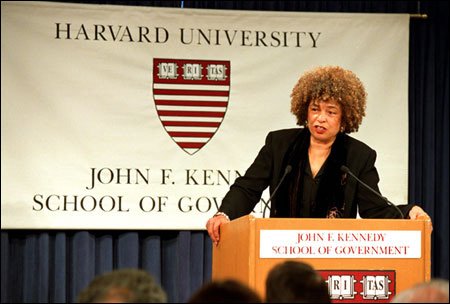

In a lecture at the Kennedy School of Government’s ARCO Forum Friday (March 7), activist and intellectual Angela Davis advocated for the abolition of prisons, casting the issue in human rights terms and urging a broader vision of justice.

“My question is, Why are people so quick to assume that locking away an increasingly large proportion of the U.S. population would help those who live in the free world feel safer and more secure?” she said.

Davis, an icon of the radical political activism of the late 1960s and early ’70s, spoke of prisons not as a tourist but as a former resident. She spent more than a year in prison before she was acquitted, in 1972, of charges of murder and kidnapping related to the failed escape of a group of African-American prisoners known as the Soledad Brothers in California.

Now a professor in the history of consciousness department at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Davis may have tamed her trademark Afro but her ideas remain on the radical edge of the political spectrum. In this talk, the 2003 Maurine and Robert Rothschild Lecture co-sponsored by the Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for Afro-American Research, and the Institute of Politics, she dismissed prison reform – the most prominent form of prison activism – as not going far enough.

“We have to go beyond the amelioration of prison practice,” she said, acknowledging that prison reforms are also necessary and many strides have been made internationally in that arena.

Within the prison reform movement, prison abolitionists, she said, are often viewed with mystery and skepticism and considered utopian.

“This is a measure of how difficult it is to envision a social order that does not rely on the threat of sequestering people in dreadful places designed to separate them from their communities and their families,” said Davis. “The prison is considered so natural and so normal that it is extremely hard to imagine life without them.”

Drawing comparisons to other abolitionist movements throughout history, Davis said that her hope is that the abolition of prisons might attract the same vigorous international debate the death penalty has. But prison remains a far more pervasive and durable idea in our imaginations.

“Prison is considered an inevitable and permanent feature of our social lives,” she said.

The prison industrial complex

Davis supported her argument with sobering facts about the proliferation of prisons and the disproportionate incarceration of minorities. In black, Latino, and Native-American communities, she said, people have a far greater chance of going to prison than of getting a decent education, and young people are choosing the military to avoid what they see as an inevitable trip to prison.

There may be twice as many people suffering from mental illness in jails than in mental hospitals.

And while the “tough on crime” initiatives of the 1980s did not produce safer communities or a significant drop in crime rates, she said, it led to a remarkable proliferation of prisons. Indeed, some have dubbed the economic sector that has arisen around prisons a “prison industrial complex.”

Despite these facts – many of which are not unfamiliar – we take prisons for granted, Davis posed, because we are afraid of the realities they produce. What goes on within prison walls is a mystery to most of us, and our collective imagination has cast prisoners broadly as “evildoers” and, primarily, people of color. In addition, by perceiving all prisoners as murderers and rapists, we further distance ourselves from the more nuanced reality of prisons.

Such abstractions, said Davis, make prisoners vulnerable to human rights abuses and lets us turn a blind eye to the larger issues behind prisons and incarceration.

“It relieves us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society, especially those produced by racism,” she said.

From punitive to restorative justice

Shifting strategies from punitive to restorative justice involves not only changing the way our system addresses crime but also getting at some of the roots of crime. We must work, Davis said, to transform “the social and economic conditions that track so many children from poor communities, especially communities of color, into bad schools that look more like juvenile detention centers than they look like schools.”

A woman from Boston’s urban Roxbury neighborhood – “I live in the belly of the beast,” she said – challenged Davis’ vision for prison abolition with respectful curiosity. Young boys sell crack on her street, she said, and she wants them gone. If not to prison, where?

“You can’t think myopically,” said Davis. “There is no place else [for the boys], so the default solution is prison. Why don’t we have other institutions?”

She argued that better schools, recreation centers, and other youth resources – and community activism that matches education activists with prison abolitionists – were some possible solutions for Roxbury and beyond.

“Our most difficult and urgent challenge to date,” she said, “is that of creatively exploring new terrains of justice where the prison no longer serves as our major anchor.”