Putting a dollar value on a good name:

Kennedy School researcher probes eBay’s honor system

“Who steals my purse steals trash; ’tis something, nothing; ‘Twas mine, ’tis his, and has been slave to thousands; But he that filches from me my good name robs me of that which not enriches him, and makes me poor indeed.” – William Shakespeare, “Othello”

For centuries philosophers, playwrights, and poets have proclaimed the excellence of a person whose word is their bond and the value of that person’s good reputation.

Poetry has it that a person’s reputation is priceless, but in our modern society that ideal has been called into question. Advertising has become high art, and perception sometimes seems to matter more than reality. The new technology that characterizes the age seems to have created endless new playgrounds for frauds, cons, and criminals.

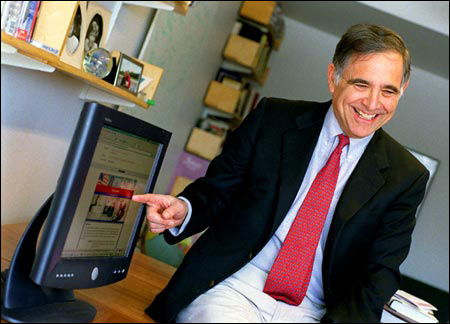

But it turns out that the poets are right, according to Richard Zeckhauser, Frank Plumpton Ramsey Professor of Political Economy at the Kennedy School of Government.

Zeckhauser’s research has determined that a person’s good reputation is not only valuable, but it’s worth about 7.6 percent in a retail transaction.

Zeckhauser, together with colleagues Paul Resnick and Kate Lockwood at the University of Michigan and with vintage postcard seller John Swanson, has completed his second National Science Foundation-supported study of the online marketplace eBay, where things are bought and sold electronically over the Internet. Though eBay does police its vendors for fraud, it is known as a freewheeling market where whatever is on the block – from everyday items to rare pieces – goes to the highest bidder.

“It shuttles things from your basement to my living room and turns junk into treasure,” Zeckhauser said. “This is what economists love, shifting something from a place where it has no value to a place where it has a great deal of value.”

Those with a cynical view of economic transactions might be surprised that eBay works at all. Transactions are mostly between individuals who have never met, for items the buyer has never seen with his or her own eyes. In addition, unlike a retail purchase in a store, where the buyer knows where to go and complain and, if needed, bring legal action, it can be more complicated to get satisfaction from someone who lives halfway across the country whom you’ve never met.

So the system operates on trust.

At the end of every transaction, the buyer gets to rate the seller. That rating goes along with the seller and can be checked by future customers, making the seller in effect put his or her reputation on the line with every transaction. Given the immediacy of eBay’s electronic marketplace, sellers also know that their reputation will be readily available to millions of potential buyers.

Zeckhauser said eBay’s brand of arms-length transaction provide perhaps one of the best opportunities to examine the economic importance of reputation. Though Zeckhauser said he’s sure that other reputation studies have been conducted on brick-and-mortar sellers, it’s very difficult to isolate reputation from the many other factors that create business success for a retailer in a community. Things such as location, civic associations, store layout, atmosphere, and even the personality of the seller can all affect how a buyer perceives his or her experience in a traditional retail store.

In eBay’s electronic marketplace, Zeckhauser was able to strip out all those external variables and isolate reputation. He and his colleagues auctioned carefully matched items – five vintage Valentine postcards, for example – from the two sellers. One seller had a superb, long-established reputation, which on eBay means many buyers had posted positive feedback after their transactions. The second set was auctioned by the same seller, but under a newly established identity with little or no track record.

After selling 200 matched pairs of vintage postcards, the established identity had brought in 7.6 percent more, on average, from his transactions.

“It’s a pretty fair rate of return for having a good reputation,” Zeckhauser said.

The success of eBay, though it may surprise some, is akin to many other kinds of successful social interaction, Zeckhauser said. Many societal conventions to which we adhere every day are dependent on common courtesy to function. He gave the example of a busy traffic merge, where people take turns advancing from alternate directions. It would only take a couple of people breaking that turn-taking convention for the system to break down, creating a traffic snarl.

“There are many social institutions that work, though on paper they shouldn’t,” Zeckhauser said.

The study, detailed in a working paper that has been presented at several conferences, is Zeckhauser’s second involving eBay. The first, also conducted with Resnick and completed last year, analyzed all eBay transactions from the first half of 1999, some 13 million pages of data. That study found that the feedback system that creates eBay reputations was widely employed, for more than half of the transactions, in fact. That study also showed that, perhaps surprisingly, more than 99 percent of feedback on sellers was positive.

Zeckhauser said the eBay reputation system is a good example of a system that works. There are others in wide use in our society that do not, however. The system of job references, he said, almost always provides positive feedback, even when the person was fired from a previous position.

With online retailing likely to become more and more prevalent, Zeckhauser said, it’s important that economists understand the dynamics of systems like that employed by eBay. Zeckhauser and Resnick have applied for further National Science Foundation funding, in part to survey eBay users to understand their viewpoint.

“These electronic markets must be understood. They are going to become much more a part of our lives,” Zeckhauser said.