McLane wins reviewing award

Reviewing books can be a thankless task. To do the job conscientiously requires many hours of attentive reading, perhaps additional hours of collateral research if one is not an expert on the subject, followed by an often agonizing session of massaging an unruly cluster of reactions into a cogent, accessible, and impossibly brief piece of writing.

To make matters worse, the work is often poorly paid and is more likely to make enemies than to make one’s reputation. Yet where would we be without intelligent reviewers to keep us in touch with all the books we don’t have time to read?

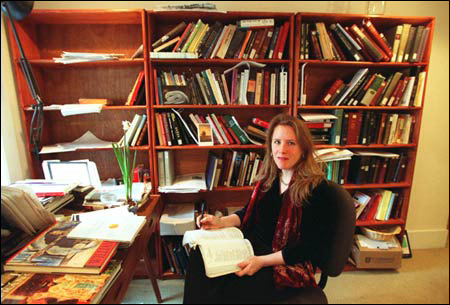

To compensate reviewers for the insult and injury to which their profession subjects them, the National Book Critics Circle each year names a winner of the Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing. The prize will be presented Feb. 26 in conjunction with the organization’s coveted awards for fiction, nonfiction, biography, poetry, and criticism. This year’s citation goes to Maureen McLane ’89, currently a junior fellow in the Harvard Society of Fellows.

For McLane, reviewing books in the popular press (the four reviews for which she is being recognized appeared originally in the Chicago Tribune) is one of several forms in which she has demonstrated her talent. She also writes poetry and essays and is currently trying her hand at a play while working on her second scholarly book on the literature and ideas of the Romantic period. Her first book, “Romanticism and the Human Sciences: Poetry, Population, and the Discourse of the Species” (Cambridge University Press, 2000), is based on her Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Chicago.

“Some people claim to be astonished that an academic can write intelligibly for a mass audience, but there’s something very refreshing about having these other genres at hand. I hope it keeps my scholarly writing a little more fluent.”

While this writer has not yet read McLane’s scholarly prose, he can aver that her reviewing has fluency to spare, often combining formal and colloquial language into a seamless but jazzy whole. Her review of Nick Tosches’ novel “In the Hand of Dante,” for example, starts out by describing the book as “A revolting, sentimental, violent, occasionally gripping, intermittently erudite, hybrid whackjob.”

But there’s more to her writing than flashy syntax. In her largely negative but respectful review of the Tosches book, she conveys a vivid sense of this idiosyncratic and complex novel as well as an incisive account of its author’s place in the current intellectual and cultural landscape.

“I think one purpose of reviewing is to give people a sense of what the work is in its own terms, to provide a window on contemporary cultural activity.”

McLane can reveal the virtues of a quiet, potentially overlooked work as effectively as she can cut an inflated reputation down to size. Her review of “10th Grade” by Joseph Weisberg, a funny, insightful novel about the quintessential suburban adolescence, opens the book’s delights to us with measured persuasiveness appropriate to its gentle comedy.

In a review of a book of short stories by Fanny Howe, McLane manages to convey the grim pessimism of these tales (“This is not, in other words, an Oprah book”), yet still leaves the reader with the sense that it is an important collection and well worth reading.

In another piece in which she reviews three very different books of poetry, she conveys a sharp impression of each poet’s unique voice and the very different ways in which they utilize language, ranging from Louise Glueck’s “poetics of the stark statement, the urgent question” to Elizabeth Alexander’s subjective musings on history and race to Christian Boek’s exuberant word-play.

In switching from writing about the impact of ballad collecting on Romantic poetry (her current scholarly project) to writing book reviews for a major newspaper, McLane admits that there is “certainly a change of stylistic gears,” and that she may avoid certain literary terms that she calls “the jargon of the tribe.” But she denies that she ever writes down to her audience.

“Respecting your audience doesn’t mean throwing a lot of esoteric words and phrases at them, but rather respecting their intelligence. I think one can try to marry complexity and transparency.”

Perhaps that respect for the intelligence of her audience comes out of her own willingness to take chances, to explore unfamiliar genres, and to step outside the area in which she has established her credentials.

“Some people like to be experts. I don’t need to be an expert for every moment of my life. I think that in reading you’re always encountering the unknown. I look on everything I do as an experiment.”