Having your cake and eating it, too:

It also might extend your life

You always hear people say, If scientists can send men to the Moon, why can’t they find a way for us to eat what we want and not get fat? And why can’t they invent a pill that will extend our lives?

Researchers have now taken a first step in both directions. Whether it will be a small step or a giant one is yet to be determined.

Drastically restricting calories increases the longevity of many lab animals, and some highly motivated humans are trying the same thing. But the eating restrictions are too harsh for most people – and no one has proved that it works.

That’s the same objection people have to the best formulas for staying slim. But, again, eating right and exercising regularly require a level of discipline that unnerves most of us.

Now, researchers at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston and the Harvard Medical School have found a way that allows mice to eat whatever and whenever they want without getting fat. They are only mice, but the experiments are well worth pursuing because the mice also live longer than normal for rodents and they don’t get diabetes.

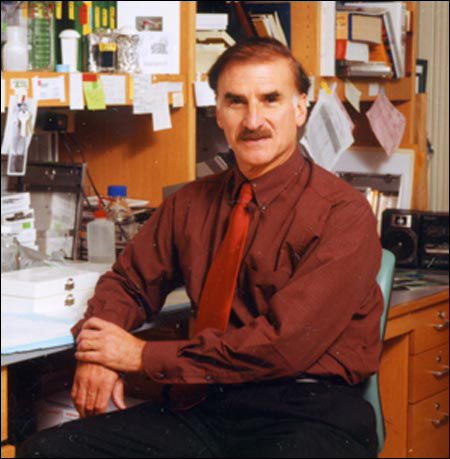

“Perhaps one day, if we are able to find a drug to do the same thing in humans, we might be able to prevent obesity, as well as type 2 diabetes and other metabolic diseases. And, who knows, we might live longer, too,” says C. Ronald Kahn, leader of the research team and Mary K. Iacocca Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. That hope may not be far-fetched. Mice share most of their genes with humans; that’s why they are picked for so many laboratory experiments.

FIRKOs live longer

Kahn was working with Matthias Bluher, of Joslin and Harvard Medical School, and Barbara Kahn, a Harvard professor of medicine who is not related to Ronald. They were investigating the link between decreased body fat, the activity of insulin, and longer life. (Insulin is involved in converting food into energy.) To get the information they wanted, the team used genetically engineered mice without insulin receptors on their fat cells. These rodents are known as FIRKOs, for fat-specific insulin receptor knockouts. Their gene for binding with insulin has been knocked out.

FIRKOs eat all they want and still stay lean. Even when encouraged to overeat, they don’t gain extra weight. Why would the inability of their fat cells to respond to insulin keep them lean? “Since insulin is needed to help the cells store fat, these animals had less of it, and were protected against the obesity that occurs with aging and overeating,” Ronald Kahn explains.

What may be more important is that FIRKOs live longer than their relatives who eat the same amount of food. They extended their lifetimes 18 percent, or from 25 to about 30 months. After 30 months, 80 percent of the FIRKOs were still eating well, while 50 percent of the normal mice had died. For humans, an 18 percent increase would add more than 14 years to the life of someone who would normally die at age 80.

FIRKOs of all ages showed a 50 to 70 percent reduction of fat, despite the fact that they ate normally or even overate. It’s a long way from specially bred lab animals to humans who want another slice of cake, but it could be the light at the end of the scale for the estimated 60 million people in the United States who are overweight. Moreover, these mice were protected from type 2 diabetes, which affects an estimated 17 million Americans.

“The results of our studies … are consistent with the view that leanness, not fat, is a key contributor to extend longevity,” Ronald Kahn says.

How this happens remains unknown. Decreasing body fat may reduce the production of oxygen-free radicals, long associated with aging. Another possibility is that altering the action of insulin may somehow be responsible. Different researchers have found that genetic mutations that alter the activity of insulin increase the life spans of other lab animals.

It will require much more research to determine if the Kahn team has taken a giant step fatward.