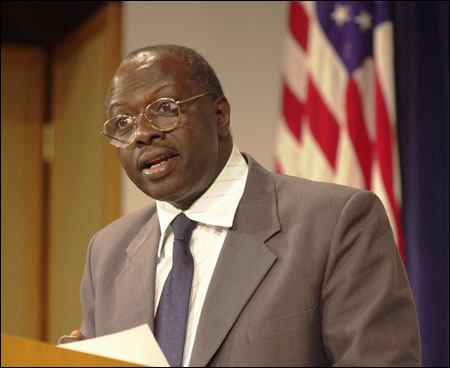

UN’s Diouf addresses hunger

‘The world hunger problem is clearly political, not technical.’

Diouf, a native of Senegal, addressed the political dimensions of world hunger, arguing that although the world has the economic and technological capacity to feed all its inhabitants, well-intended but poorly directed policies have prevented the realization of this goal.

“One of the great successes of the 20th century was a rate of growth in food output that considerably surpassed the unprecedented rate of population growth,” said Diouf, adding that equal distribution of all the world’s food would provide everyone on the planet with a robust 2,800 calories per day, a 17 percent increase from 30 years ago.

But, he said, “agricultural gains in the last decades have not been translated into food for all.” Instead, 6 million children under the age of 5 die each year from hunger and malnutrition; undernourishment exacts a heavy toll on the health and productivity of not just individuals but their communities and nations as well.

“The fact that so many of our fellow beings are not adequately fed and therefore not able to lead a full life suggests that there is something fundamentally flawed about the way in which our world is being managed,” said Diouf. “The world hunger problem is clearly political, not technical.”

Part of the problem, he said, is a paradox: Higher food productivity, combined with large subsidies, has driven down prices and had a negative effect on small, rural farmers in developing nations.

Also to blame is political will that goes unbacked by dollars for action. At the World Food Summit in 1996, 186 countries pledged to cut in half the number of undernourished people in the world by 2015. Yet development assistance to agriculture has fallen by 50 percent in real terms since the late 1980s, he said.

Diouf also blamed an outlook that sees the eradication of hunger as a consequence, not a cause, of economic growth, and a worldwide perception that hunger is no longer a major problem. The global availability of food, declining food prices, and a belief that food production technology can keep up with demand may have created the false impression “that enough food for everybody means that everyone has enough to eat,” he said.

Diouf offered a plan by which the World Food Summit goal of seriously mitigating hunger by 2015 could be reached at a cost of $24 billion. Gains in health and productivity, he said, would total $120 billion. He called for financial partnerships between the governments of developing nations and international donors, and he stressed that measures must be taken to level the playing field of trade for developing countries.

But the problem, like the solution, is not just about economics.

“Hunger and extreme poverty bring about conflict, especially of ownership and access to resources,” Diouf said, adding that hunger contributes to global issues of migration and international crime. Ending hunger, he said, goes beyond a moral imperative to serving the self-interest of all countries, rich and poor.