In their cups:

Cummins solves the enigma of Inca drinking vessels and other mysteries of Andean and Mesoamerican art

It has been said that history is written by the winners.

Perhaps there is no more striking illustration of this axiom than the rise of the colonial empires of Latin America. Built on the ruins of the powerful, sophisticated Inca and Aztec civilizations, the Spanish colonies all but erased the history and culture of the peoples whose land and wealth they appropriated.

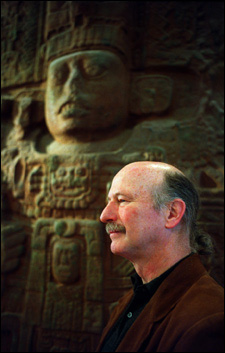

Almost, but not entirely. Much remains if one knows where to look. Thomas Cummins, who joined the faculty in 2002 as the Dumbarton Oaks Professor of the History of Pre-Columbian and Colonial Art, has made a career of finding and interpreting objects that hold the key to a fuller understanding of the encounter between native peoples and their Spanish conquerors.

“Indigenous people weren’t winners, and, with few exceptions, they didn’t write histories,” Cummins said. “But with a little perseverance, you can find the objects that enable you to tell history from the other side. That’s the driving force for me, because without that perspective, our knowledge of the encounter between indigenous peoples and Europeans would be one-sided.”

Cummins’ latest book is a fine illustration of this effort to achieve a more balanced view of history by interpreting indigenously crafted objects whose significance has not been fully understood. The book is “Toasts With the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Kero Vessels” (University of Michigan Press, 2002). In it, Cummins explores a theme that has been recurrent in his work – the ways in which indigenous forms changed as a result of colonial influence.

The book focuses on ritual Inca drinking vessels and the transformation of their decorative designs from geometric abstraction to pictorial representation. Cummins asks how and why these vessels changed over time and why the Spanish allowed them to be manufactured well into the colonial period after most other expressions of indigenous religion had been banned or forced underground.

He finds that the cups represented a compromise between the Inca and the Spanish authorities. While the vessels’ increasingly pictorial images of gods and myths served to remind the Inca of the pre-Hispanic past, their continued use and manufacture helped to maintain social relations between the Indians and the Spanish that were essential to the vitality of the Spanish colony.

Cummins’ ability to interpret the complexities of the Indian-European encounter through the language of artistic images has impressed his colleagues, not only in the history of art and architecture but in other disciplines as well.

John Coatsworth, the Monroe Gutman Professor of Latin American Affairs and director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, called Cummins “the world’s foremost historian of the art and culture of the era of the Spanish conquest and colonization of the Andes and perhaps of the rest of Latin America as well. His work draws on his extensive knowledge of pre-Conquest indigenous cultural achievements as well as Spanish art and architecture of the era to understand the amazingly rich but also deeply contradictory artistic production of the colonial era.”

Anthropologist Gary Urton, the Dumbarton Oaks Professor of Pre-Columbian Studies, praised Cummins’ extensive knowledge of pre-Columbian art and his expertise in the arts of the Andes and Mesoamerica.

“Finally, Tom writes beautifully about both mundane, everyday objects that were a part of the everyday lives of people throughout Latin America in earlier times, as well as about those works of art – such as public stelae, fine objects of gold and silver, church paintings – that were prominent in the public cultures of Pre-Columbian and early colonial societies in Latin America. In short, Tom is interdisciplinary and comparative to the core, and he is a wonderful addition to the Harvard faculty,” Urton said.

Yve-Alain Bois, the Joseph Pulitzer Jr. Professor of Modern Art, and chair of the History of Art and Architecture Department, said that “if anything stands out among Cummins’ many accomplishments, it is indeed the interdisciplinarity of his work. This quality, which is a direct consequence of the extraordinary range of his interests and expertise, is that which appeals most to everyone who has been exposed to his work. It ensures its relevance not only for all scholars of Latin America, whatever their discipline, but also for art historians of all persuasions working in any field.”

Considering Cummins’ pre-eminence in his field, it comes as some surprise to learn that he came to the study of pre-Columbian and colonial art as the result of what might be called an impulsive decision. As an undergraduate, he had been interested in Medieval European art. Then in his sophomore year, he decided to accompany his girlfriend (now his wife) on a study program in Bogota, Colombia. Three months’ exposure to the art and culture of the Andes convinced him that this was the area he wanted to study.

“I always tell my students, do what you really want to do. Otherwise you just go through the motions.”

Cummins has continued to follow this philosophy in his scholarly career, choosing projects that appeal to him in some mysterious, intuitive way.

“It always starts when I see something I really like visually but that I don’t understand, and I know I’ve just got to find out about it.”

Often, it turns out, these mysteriously intriguing objects have fascinating stories to tell. For example, one of Cummins’ articles had its origin in an Aztec painting showing rows of objects and human figures. Cummins’ research revealed that the painting had been used as evidence in a 16th century trial in which Hernan Cortés, the conqueror of Mexico, sued the governor of Mexico City, whom he accused of taking his lands and possessions. The painting was a visual inventory of the goods and slaves belonging to Cortés.

Another group of objects that Cummins has studied encapsulates a complex series of cultural and political encounters in the form of copies of a famous painting. The original was Titian’s equestrian portrait of Emperor Charles V. Charles’ son, Philip II, commissioned a copy of this portrait to be sent as a gift to the emperor of China. Philip’s real motive was to determine if China could be added to Spain’s colonial conquests as Mexico and Peru had been.

The painting, however, stopped in Mexico City, where it remained. There it was seen by Aztec feather workers who copied it in the form of a ceremonial shield and sent it back to Philip II as a gift. It is now part of the royal collection in Madrid.

“Objects like these tell stories that are extremely complex. They’re a way of talking about power and colonial relations, about what the Spanish saw and what the Indians saw,” Cummins said.

Before coming to Harvard, Cummins taught at the University of Chicago. He received a bachelor’s degree from Denison University, Granville, Ohio, in 1973, and his master’s (1980) and doctoral degree (1988) from University of California, Los Angeles. In addition to the recently published “Toasts with the Inca,” he is the author of numerous articles and is the co-editor (with Elizabeth Boone) of “Native Traditions in the Postconquest World” (Dumbarton, 1998) and (with Emily Umberger) of “Native Artists and Patrons in Colonial Latin America” (Arizona State University, 1995).