Fine art, cutting-edge science meet at Straus Center

High atop the Fogg Museum, Henry Lie, director of the Straus Center for Conservation, and art historian Francesca Bewer study an X-ray, pointing to the milky image and scratching their chins in thought. A warrior – or rather, a 16th century bronze cast of a warrior by Dutch sculptor Willem van Tetrode – has broken his arm, and they look closely at the fracture and the pins that reset it.

Down the hall, in a laboratory crowded with microscopes and other analytical equipment, senior conservation scientist Gene Ferrell uses FT-IR, Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy, to study a pigment sample from a mummy case that dates to 800 B.C.

Straus Center video:

Real video (3:34)

And in a noisy, dirty room around the corner – “we call it the Noisy Dirty Room,” says Lie – a high-powered laser device uses technology borrowed from the medical industry to blast away layers of paint from a plaster sculpture.

Fine art and cutting-edge science meet head-on at Harvard’s Straus Center for Conservation, one of the nation’s oldest but most technically advanced centers for art conservation. The unlikely but happy coexistence of old and new is advancing the field of conservation with more information about centuries-old art and less invasive ways to restore and maintain its original beauty.

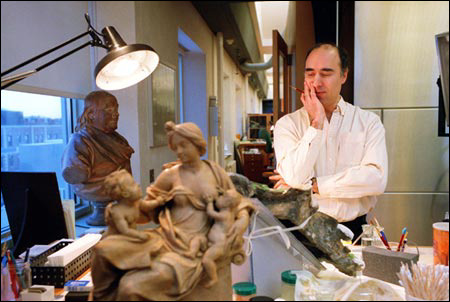

Lie, who joined the center staff in 1980 and became director in 1989, describes art conservation as equal parts art history, studio art, and science – disciplines that “are completely different and perhaps antithetical to each other,” he admits.

The Straus Center now has two dedicated art historians and two scientists, including Ferrell, a geologist by training, on its staff of 20. Several conservators work in each of the center’s three conservation areas: paintings; works on paper, including photographs, drawings, and watercolors; and objects.

Technology originally used in medicine and other scientific fields has brought new sophistication to what conservators and historians know about art, and thus to how they can more effectively and less aggressively conserve it for future generations.

Enhanced instrumentation, for instance, means conservators can make thoughtful analyses and materials comparisons from tiny samples, such as Ferrell’s smaller-than-pin-sized pigment sample. His data will help conservators and historians understand the materials used in painting the mummy case without damaging the original work.

“Sample size is critical to a lot of art studies,” says Lie. “Some things are precious and small or have very perfect surfaces that simply cannot be sampled.”

Visualization techniques, like the X-radiographs that Lie and Bewer study, reveal valuable data about a work’s creation. Looking at the van Tetrode sculptures, they can see evidence of casting techniques that may eventually link each object to a particular sculptor or workshop, information that is crucial in a reproductive medium like casting.

Adjacent to the painting studio, infrared reflectography lets conservators peer through layers of paint (and often a haze of accumulated grime) to the artist’s original underdrawing on the canvas.

“That’s a good example of something that simply did not exist until the last two decades,” says Lie.

While equipment and techniques may be up-to-the-minute, science has had a toehold in the Straus Center since its founding in 1928. Chemist Rutherford Gettens was an early staff member, hired by the museum’s first director, Edward W. Forbes, to work with the Center’s extensive collection of pigments and other artists’ materials. A valuable historical resource, samples from the collection now live in museums and conservation departments around the country.

Amidst the Straus Center’s high-tech wizardry, however, much old-school art conservation persists. Objects conservator Tony Sigel shows off his handiwork on a 16th century Italian terra-cotta relief plaque that “almost looks like it was rolled down a staircase,” he says. “Everything that sticks out was broken off.”

Sigel rebuilt the image’s smashed-off nose and re-created decorative ribbons by studying other works from the same period. And while science and technology make it possible to restore the piece entirely, Sigel draws on a higher aesthetic for restraint.

“Leaving some of the damage that you see here … informs the viewer in a subtle way what it’s made of, how it’s made,” says Sigel. “You don’t want to remove all the evidence of its previous life and the battle scars it’s encountered.”

Share this article