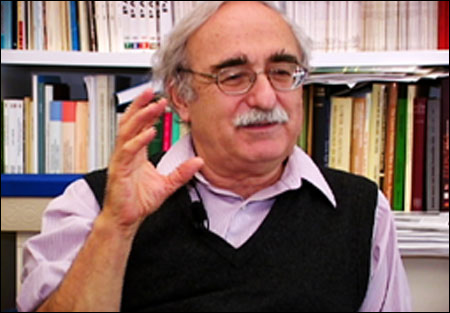

Bar-Yosef reads ancient campfires:

Archaeologist uncovers secrets of human origins

Archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef is an interpreter of ancient human history as told by barn owls, a sleuth in search of mankind’s past, reading the ashes of campfires extinguished millennia ago and examining stone flakes for evidence of a human hand in their creation.

For much of his academic career, Bar-Yosef’s focus has been the Stone Age – known as the Paleolithic – when early Homo sapiens went by the name Cro-Magnon and lived side by side with a human cousin, the Neanderthal.

His work, conducted with colleagues from the United States, France, and Israel, has focused on three Israeli caves that paint a picture of early habitation by modern humans migrating north out of Africa and a later migration by Neanderthals south out of southeast Europe or Turkey. It is this mix of human species and the later departure of Cro-Magnon man out of the Middle East to colonize Neanderthal-dominated Europe that fascinates Bar-Yosef.

Bar-Yosef, Harvard’s MacCurdy Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology and head of the Peabody Museum’s Stone Age Laboratory, is now shifting his attention to a later period, the New Stone Age, known as the Neolithic, when Homo sapiens first domesticated plants. He’s particularly interested in the rise of agriculture, dubbed the Neolithic Revolution, a transforming event in human history that set the stage for early villages and the larger civilizations to come.

It’s his interest in an earlier prehistoric revolution that spurs Bar-Yosef’s investigation of the Neolithic. Bar-Yosef believes it was some type of technological revolution that gave Cro-Magnon humans the upper hand over Neanderthals some 35,000 years ago. It was at that time, after thousands of years of coexistence, that Cro-Magnon began to multiply rapidly, expanding into a Neanderthal-dominated Europe and into Asia. It is also at that time that Neanderthals began to decline, eventually disappearing entirely.

Some believe there was a change in the brain that explains Cro-Magnon success, though no evidence of it has been found from remains of the time. Perhaps it was a change in the brain or elsewhere that, though undetectable in remains that have survived, meant the difference for Cro-Magnons between merely surviving and thriving.

Bar-Yosef looks to more recent history for a different explanation. The Industrial Revolution also transformed human society, he points out, yet was clearly a product of human innovation, not human biological evolution. A future archaeologist looking back at that period of time might conclude that it was a neurological change that gave humans the sudden capacity for industrial innovation.

They’d be wrong. The Industrial Revolution was an accident of timing, the sudden flowering of centuries of slowly accumulating knowledge that triggered a cascading avalanche of industrial development.

Bar-Yosef asks why a similar revolution couldn’t have happened 35,000 to 40,000 years ago, during the Upper Paleolithic. New technology, he said, could have made a huge difference in the success of early human communities.

“It was a new, improved hunting technique, probably coupled with a means for long-range communication, say drums, that enabled early groups of Cro-Magnon to become better hunters and better monitors of the environment, and to communicate that to others,” Bar-Yosef surmises. “That would have led to better survival of babies, to population increase – more rapidly among Cro-Magnons than among Neanderthals.

Rice grain in a haystack?

Bar-Yosef’s work on the agricultural revolution will take him to Turkey and China. Like the much later Industrial Revolution, experts agree that the Neolithic’s agricultural revolution occurred as a result of a new technology – in this case the domestication of crop plants – and not some physiological change that suddenly made the time’s human hunters better suited for farming.

The rise of agriculture had far-reaching effects. With the ability to plant crops, people were assured a more steady food supply. Agriculture led to more permanent settlements and, ultimately, to the rise of civilization.

While much is known about the rise of agriculture in the Near East, less is known of its progress in China. Looking for the location where rice was originally cultivated may seem like searching for a needle in a haystack, but Bar-Yosef said he and fellow scientists will use what they know about the climate of the period to determine likely environments where the progenitor wild rice plants might have grown. It is in these places, he said, that they will focus their search for early agricultural communities.

“Historians look at the Industrial Revolution, and most agree when and where it took place, but have different opinions on why,” Bar-Yosef said. “The same thing with the Neolithic Revolution, people agree with when and where but not on why. In China, even where and when hasn’t been found yet.”

The micro-mammal trail

Bar-Yosef’s scientific journey started in Kebara Cave in Israel in 1982. While excavating the cave, he and several collaborators found Neanderthal remains dating back to 60,000 years ago, fairly late in the Neanderthal timeline, which began some 300,000 years ago in Europe. The Neanderthals, it appeared, had been fairly late arrivals to the Mediterranean’s eastern coastal region known as the Levant.

The group working at Kebara was using relatively new thermoluminescence and electron spin resonance dating techniques, an improvement over radiocarbon dating, which cannot date fossils earlier than 40,000 years ago. In addition to using the new techniques at Kebara, they applied them to the fossil-bearing layers at a nearby cave, Qafzeh.

Qafzeh, about 25 miles away, was a cave with an archaeological past. It was first excavated in the 1930s. It was excavated again in the 1960s by Bernard Vandermeerasch from the University of Bordeaux. Bar-Yosef did additional work there in the late 1970s with Vandermeerasch. Human fossils, mostly in well-organized burials, had been found in Qafzeh. The fossils resembled modern humans. Under the prevailing thought of the time – that Neanderthals were the ancestors of modern humans – the Qafzeh remains should be more recent than the Neanderthal remains at Kebara.

But Bar-Yosef had a feeling that wasn’t the case.

His feeling stemmed from a combination of evidence, including climatic clues from sediment layers in the cave and studies of the remains of micro-mammals such as rats, mice, squirrels, and other small animals at Qafzeh conducted by the late Eitan Tchernov of Hebrew University.

Micro-mammals are an important indicator in figuring out who was living in a cave when. That’s because the animals are the prey of barn owls – and barn owls only like caves without human lodgers. Barn owls also have a very archaeologist-friendly way of dining – they eat their small mammal meal and then regurgitate the bones, creating a litter of bones on the cave floor.

By classifying these bones and comparing them to a sequence of known layers, zooarchaeologists can tell not only what kind of mammals the owls were eating but also when. Mice, for example, are generally found in warmer and drier climates. By comparing layers with many mice bones with those dominated by other rodents, archaeologists can track the region’s climate as it became wetter and drier over time.

Bar-Yosef felt that the sediment layers and micro-mammal remains at Qafzeh indicated that Qafzeh’s human remains were older than Kebara’s Neanderthal remains and not younger as it was once supposed.

“I had a feeling the deposits in Qafzeh cave were much older,” Bar-Yosef said. “The stratification of how things accumulated, it was very clear, according to micro-mammals, that it should be older than Kebara.”

Sure enough, after dating the Qafzeh remains with the new technology, they were found to be 92,000 years old. With early modern human remains in the region predating the Neanderthal remains, it became apparent that Neanderthals couldn’t be human ancestors and were instead contemporaries.

That discovery shook up the prevailing scientific view of the time that Neanderthals were direct human ancestors and grandfathers of Cro-Magnons on the human family tree. The remains at Qafzeh proved that Neanderthals and the ancestors of modern humans diverged at some point, with Neanderthals existing at the same time as Cro-Magnons, more akin to cousins of modern humans than grandfathers.

The beginning of the story at Hayonim

From his work at Kebara and Qafzeh, a picture was emerging of early modern humans as the Levant’s original occupants. That picture showed that Neanderthals were latecomers, pushing south and east from their native Europe. Bar-Yosef then turned his attention to the beginning of the story, looking for indications of when those early human Cro-Magnons first came from Africa.

To do that, Bar-Yosef and several American, French, and Israeli collaborators turned to Hayonim Cave in the Galilee in 1992. After eight seasons totaling almost a year of fieldwork, they wrapped up their work at Hayonim in 2000. Bar-Yosef said that, though no human remains were found during that work, the cave helped illustrate how those first immigrants from Africa lived.

What they did find – stone tools, fireplaces, plenty of ashes, and huge quantities of small mammal remains, again deposited by barn owls – paints a picture of intermittent human occupation, Bar-Yosef said. The tools and ash show that humans did use the cave, while the large number of small mammal remains show that barn owls ruled the roost for long periods of time, indicating that humans were absent from the cave for those periods.

Together, he said, the clues point to a people who were adept at making advanced stone tools, who were proficient and mobile hunters, and who collected wood to make fire.

“We know today they were all hunters and gatherers, they brought game back into the cave and roasted it. They cracked the bones for marrow,” Bar-Yosef said. “Hayonim cave excavations provided us with the story of how humans lived some 250,000 to 150,000 years ago and produced the only rich assemblage of animal remains from that period in the Middle East.”

Though his work has been revealing about the Levant’s prehistory, it leaves unanswered the question of what happened more recently, during that Upper Paleolithic revolution when our Cro-Magnon ancestors began to multiply and Neanderthals began to decline.

Though some believe the Neanderthals and Cro-Magnons interbred until the two populations were indistinguishable, Bar-Yosef thinks the warlike traits of people today give evidence of a different Neanderthal fate. Bar-Yosef thinks Neanderthals were either killed by Cro-Magnons with superior weapons or their populations were isolated by incoming Cro-Magnons and fragmented until, with lower reproductive rates, they died out.

To search for clues to that riddle, Bar-Yosef is continuing work at two sites in the Republic of Georgia, begun in 1996. In Georgia, Bar-Yosef is exploring sites in the Caucasus Mountains with Georgian, Israeli, and American colleagues, looking for evidence of the route early humans took into Europe. Many believe they crossed from Turkey to Southeastern Europe, but they also have traveled along the Black Sea’s eastern shores, over the Caucasus, and then west into eastern Europe.

By examining those sites, he is also looking for clues as to how modern humans came to dominate Europe. The Caucasus Mountains were an area where Neanderthals were able to exist longer than many other places, so perhaps clues to their demise exist there also.

“What we’re trying to find out is when did modern humans come out of Africa and did modern human traits spread by slow diffusion or rapid migration,” Bar-Yosef said.