Nigeria: A country at a crossroads :

Conference to explore future of deeply divided Nigeria

The Nigerian riots sparked by the Miss World Pageant brought global attention to the deep divisions between the nation’s largely Muslim north and the Christian-dominated south, highlighting regional differences that have some wondering whether Africa’s most populous nation can survive.

More than 200 people were stabbed, beaten, and burned to death and hundreds more injured by protesters after a newspaper columnist belittled Muslim criticism of the Miss World Pageant. The columnist, asking what the Prophet Muhammad would think of the pageant, wrote that he probably would have taken one of the contestants as a wife.

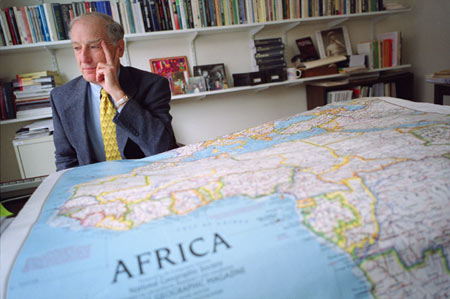

The rioting, which broke out in the northern city of Kaduna, prompted pageant organizers to move the Dec. 7 event to London from the Nigerian capital of Abuja. The conflict illustrates the delicate balance being struck in Nigeria today, according to Robert I. Rotberg, director of the Program on Intrastate Conflict and Conflict Resolution at the John F. Kennedy School of Government’s Belfer Center and president of the World Peace Foundation.

Nigeria’s future will be examined at a three-day conference, “Nigeria: Unity, Governance, Law, and Conflict,” that begins today at the Kennedy School. The event, chaired by Rotberg, will feature senior leaders from academia, nongovernmental organizations, and government, including former Nigerian President Yakubu Gowon.

The conference’s only public event will be a panel discussion, “After the Riots: Islamic Law and the Future of Nigeria,” examining the riots and ramifications of the recent imposition of Islamic law in several northern states. It is scheduled for tonight at 6 p.m. in the Kennedy School’s ARCO Forum.

Conference attendees will formulate recommendations for policymakers in Nigeria and in nations and organizations that deal with Nigeria.

How Nigeria fares has important ramifications for the rest of Africa, Rotberg said. With more than 120 million people, it is by far the continent’s most populous nation and potentially one of its richest. At independence in 1960, Rotberg said, Nigeria’s per capita income was higher than Taiwan’s. After decades of political turmoil, corruption and mismanagement, however, the average Nigerian is 30 percent poorer than at independence.

Nigeria is an oil-producing nation that straddles Africa’s Muslim-Christian divide. It also has the dubious distinction of having the largest number of unemployed college graduates in the world. This combination of size, wealth, and human capital gives the West African nation the potential to lead sub-Saharan Africa, either into prosperity or continued decline, Rotberg said.

“If the engine of growth can get revved up in Nigeria, Western Africa can take off. If Nigeria can become a sustainably democratic place, the rest of Africa will,” Rotberg said. “Nigeria has the potential to reform Africa. It also has the potential, which it has lived up to over the last 30 years, to destroy Africa.”

Like the conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, Rotberg said, the Nigerian Muslim-Christian tension isn’t about religion. Religion, however, provides a convenient dividing line between populations that differ ethnically, culturally, geographically, and, most importantly, economically.

The roots of the tension, he said, lie in competition for jobs, patronage, control of the government, and in Muslim fears that they’re being overtaken by faster birth rates in the Christian south. Today, Nigerian Muslims officially have a slight edge in population. A completely believable and unrigged census hasn’t been conducted in Nigeria since 1953, Rotberg said, and it’s quite possible that Muslims are actually in the minority today.

“Where the United States has been called a melting pot, Nigeria should be called a ‘seething pot,’” Rotberg said.

The riots over the Miss World Pageant illustrate the sensitivity of the situation, Rotberg said, which has gotten even more touchy with the imposition of Islamic Law, or Shari’a, in several northern states. Though largely Muslim, those states have sizeable Christian minorities. The sentencing of several women to death by stoning for adultery has been contested by the national government, providing a further illustration of the increasing tension.

Rotberg said governmental leadership is one cause of the problem that will be examined during the upcoming conference. In 1999, the nation established its first civilian government after 16 years of military rule. That government, headed by President Olusegun Obasanjo, is a strong federal structure that gives considerably less authority to its 36 states than the states prefer. There are major arguments as well about how Nigeria’s oil revenues are divided.

The lack of decisive national leadership, Rotberg said, is one of the main factors in the nation’s uncertain future. Other factors, which will also be examined at the conference, include a lack of confidence in government institutions and a need to root out corruption and strengthen integrity in government.

“There’s a great potential for a Nigerian rebirth because the human potential is there and the human capital is there,” Rotberg said.