‘Lois Orswell, David Smith, and Modern Art’ offers fresh focus

Showing visitors around the Fogg Art Museum’s current exhibit “Lois Orswell, David Smith, and Modern Art,” curator Marjorie Cohn pauses at a brass sculpture by Eduardo Paolozzi. Lois kept this in her garden, explains Cohn, the Fogg’s Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Curator of Prints, and a wasp’s nest was discovered in it while mounting the sculpture on its exhibition pedestal.

“Why should we take it out? The wasps have long since left,” says Cohn.

Cohn’s comment reveals her delight in the duplicity of the exhibit: It’s as much about the art – important works from 20th century artists including Georges Seurat, Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, and above all, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and David Smith – as it is about the private, passionate, and pioneering collector Lois Orswell.

Orswell, a woman of relatively modest means with a brave and very personal aesthetic, amassed a collection of more than 350 European and American modernist paintings, sculptures, and drawings, as well as Asian and African art and sculpture, from the mid-1940s until the 1960s.

“Largely, she made [the collection] by herself without being part of the art circle at the time,” says Cohn, who developed a personal friendship with Orswell that lasted until the collector’s death in 1998. “She was certainly acting very much individually, not letting anybody else make her mind up for her.”

Video:

Real video (3:59)

By catching artists on the rise, Orswell was able to buy important works, particularly by the abstract expressionists, before they became expensive. About half her collection is on display in the exhibit, which moves thematically through the 20th century’s artistic movements.

Strong, not pretty, pictures

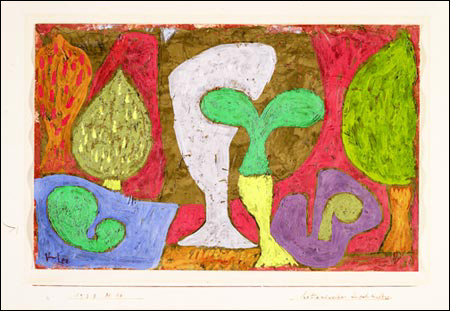

Orswell’s early acquisitions, which she selected for their emotional content, include Paul Klee’s bright gouache “Landing Boat” (1929), and “The Actors” (1941-42), a bold triptych by Max Beckmann. The latter painting, which occupies an entire wall of one gallery, came to the Fogg early, when Orswell moved from her parents’ small house in southern Rhode Island to an even smaller home in rural Connecticut.

Cohn points out the triptych’s bright colors and violent, almost scary images, noting that buying such a work from a German painter so shortly after World War II spoke to Orswell’s independence.

“She doesn’t have pretty pictures in her collection, she has pictures that are very beautiful and strong,” says Cohn.

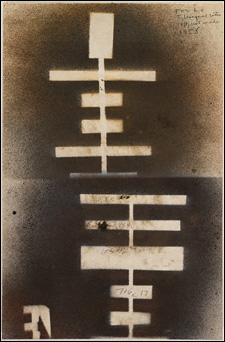

As Orswell’s tastes grew, she moved from brightly colored paintings to monochromatic cubist drawings and finally to American abstract expressionism, buying two Franz Kline drawings at his first-ever New York show.

“She recognized immediately that abstract expressionism was here and was great,” says Cohn.

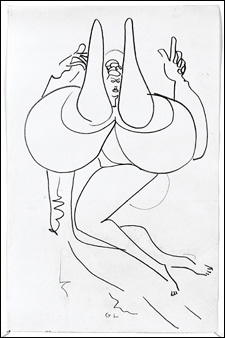

Orswell had a special affinity for the female figure, and works by Picasso, French-born American sculptor Gaston Lachaise, and David Smith embody this.

“She felt strongly that the works of art had living spirits and that they inhabited their art bodies much in the way that she inhabited her fleshly body,” says Cohn. “She had great rapport with them.”

Indeed, the gleeful drawings and bulbous sculptures by Lachaise celebrate the female form with abandon, hovering between grotesque and pornographic.

“Do you ever hear screams of horror echoing down the Fogg’s halls about the Lachaise stuff?” Orswell wrote Cohn.

Orswell collected purely for her own pleasure and spiritual growth, unmotivated by academic or financial gain. A mobile sculpture by Alexander Calder, for instance, is quite distinct from most of Calder’s work, but Orswell was drawn to it despite its lack of brand recognition.

Her relationship with David Smith, however, fostered a different kind of collecting, one with an eye toward building a representative ensemble of Smith’s paintings, photographs, and sculptures. Working collaboratively with Smith, with whom she developed a close friendship, Orswell devoted the end of her collecting career to assembling a major collection of Smith works, including the sculptures “Detroit Queen” (1957) and “Doorway on Wheels (1960).

‘She was not a sissy’

Cohn’s friendship with Orswell began with routine correspondence over the pieces that Orswell loaned, and later gave, to the Fogg. Yet it flourished, says Cohn, as they shared their passion for gardening.

Cohn tapped her correspondence from Orswell – “she was an indefatigable letter writer” – for what is traditionally curator-written commentary on the works, deepening the visitor’s connection to the art through the collector’s passionate eyes.

“I think people have a better, a less mediated approach to the collector’s own mind that way,” she says.

Cohn pauses at the Lachaise sculpture “Burlesque,” reading Orswell’s accompanying commentary aloud:

I was reading about some photogenic young woman who makes a grand salary by taking younger would-be collectors about and telling them what to buy. What sissies they are.

“That’s Lois,” says Cohn with obvious affection. “She was not a sissy.”