Long-term memory kicks in after age one:

Human brain not sufficiently developed

It’s been known for a while that babies enjoy a dramatic increase in their ability to remember people and things between 8 and 12 months of age. But this is short-term memory, the kind that loses a telephone number in a minute or less if you don’t write it down.

Long-term memory is something else. Most people recall where they were on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001. But when do humans develop this ability to remember something for most if not all of their lives?

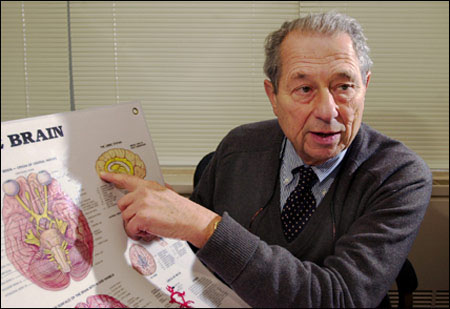

It was a natural question for Conor Liston, a Harvard senior, and his mentor Jerome Kagan, Starch Research Professor of Psychology. Liston conducted experiments under Kagan’s supervision, and they came up with an answer.

“Our findings suggest that children have great difficulty recalling the past before the end of the first year of life,” says Kagan.

Liston introduced three groups of children, 9, 17, and 24 months old, to a series of distinctive experiences. These included making a rattle by putting a plastic ring through a slot and into a bottle, then shaking the bottle. Four months later, he revisited the same kids and gave them the same toys. For the most part, the 9-month-olds, now 13 months of age, didn’t remember what to do with toys. The 17- and 24-month-olds, now 21-28 months old, however, showed robust memories of what they had seen and done with the objects.

“We interpret this to mean that, at 9 months, the human brain is too immature to firmly register experiences, while at 17-21 months it has developed enough to record and retrieve memories of single distinctive experiences,” Kagan says.

Does this mean that infants younger than 8 months to a year old don’t learn anything from mom and dad’s reading, playing with them, singing to them, and so on? “Most single experiences before age 8 months, unless they are very emotional or painful, are probably lost,” Kagan replies. “However, there are important reasons for pursuing such activities. They keep kids alert and aroused. Many studies show that children who experience lots of attention and variety are intellectually better off than those who are isolated or ignored. Variety and attention are food that makes young minds grow.”

Filling a blank slate

Not too long ago, in the 1940 and ’50s, most psychologists believed that a newborn’s mind was a blank slate. As a child manipulates things and sees the result, those experiences fill the slate with scribbles that become long-term memories. “This popular point of view held that you can teach any child anything,” Kagan comments. “That was optimistic, egalitarian, liberal, extreme, and wrong.”

Since then, battalions of neuroscientists, conducting experiments with humans and animals, have amassed data to prove that, after birth, the brain is still growing. In fact, at birth the brains of horses and goats are more mature than those of humans.

In subsequent months, cells in the frontal lobe of the brain and in the hippocampus, two regions necessary for long-term memories to form, undergo a spurt of growth. The hippocampus, a small S-shaped area deep in the brain, sends long extensions of its nerve cells to the front of the brain, and cells in the frontal cortex reach out to the hippocampus. “These circuits must be mature before long-term memories can be recorded and retrieved,” Kagan maintains.

Conor Liston wanted to know when this happens. Various researchers had tested the memories of children a month or so after exposing them to a memorable experience, but no one had checked their recall after longer delays.

Liston went to Kagan for help to do the necessary experiments. The Provost’s Office at Harvard gives grants to conduct such research under two programs, one called the Children’s Initiative, the other the Mind/Brain/Behavior Initiative. These grants are named in honor of Kagan. Liston, appropriately, won a Kagan Award.

Using mass mailings, Liston recruited 12 9-month-olds and an equal number of 17- and 24-month-olds from middle-class families in Boston. He went to their homes and demonstrated different games to the kids. For example, in “Load the Truck,” he put a toy driver in the driver’s seat of a toy truck, put a small rock in the truck bed, then rolled the truck.

Liston repeated the sequences several times, then encouraged the children to imitate what was done. He did this for three separate games. Then he went away and came back four months later.

Who can play the game

At these later sessions, the games were not demonstrated to the youngsters, but they were encouraged to play them by themselves. Each child was challenged by three games she or he had played before and two novel games.

The now 13-month-olds behaved as if they had never played such games before. They did as poorly on the familiar games as they did on the novel ones. The 21- and 28-month-olds, in contrast, showed a strong recollection for the games they had played. They performed significantly better on the familiar sequences than on the novel ones.

Liston also tested children who had never played any of the games, as a means of making sure that the sequences were not something babies might pick up naturally. The 21- and 28-month-old controls showed no skills at playing any of the games, as expected.

“We propose that this memory enhancement, or lack of it, is due to brain development between age 9 and 17 months,” Kagan says of the results, published in the Oct. 31 issue of the scientific journal Nature.

Kagan sees one practical application for the research. Many families in the United States are adopting babies, particularly from other countries. New parents often worry about whether the adoptees will have problems adjusting to new homes and cultures. “If the babies are younger than 8 months, odds are they have no lasting memories of what happened to them,” Kagan points out. “Their transition will be less disruptive and bonding much easier than for children older than 1 year.”