Kyoto first city in series on art and architecture:

Lecture series is launched with a look at Japanese city from eighth century to today

Since Kyoto does not have its own airport, most visitors arrive by rail, disembarking in the city’s new railway station, designed by Japanese architect Hiroshi Hara and completed in 1999 at a cost of more than $1 billion. The station is huge, comprising a theater, a hotel, a department store, and colossal public spaces defined by soaring expanses of glass and metal.

Postmodernist megastatements like Hara’s station are not what most people associate with Kyoto, which served as Japan’s capital from 794 to 1868 and is still considered the capital of traditional Japanese arts and spirituality. And yet the station is there, unsettling and unavoidable, which may be why John Rosenfield decided to begin his lecture on Kyoto in that spot rather than in one of the many temples, museums, or manicured gardens with which the city abounds.

“The building has been vehemently protested as an attack on the city’s heritage, a rupture with historical consciousness. But this extreme tension between modernity and tradition has been a recurrent theme,” he said.

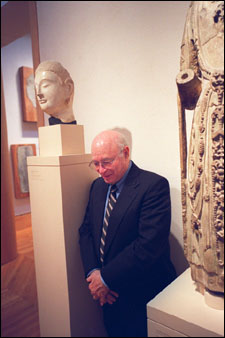

Rosenfield, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Professor of Oriental Art Emeritus, gave his talk Wednesday evening (Oct. 30) at the Fogg Museum. It was the first in a lecture series titled “Cities: Their Art and Architecture,” sponsored by the Harvard University Art Museums.

The illustrated lectures promise to be more than a visual feast. Afterward, the audience has the option of dining at the Faculty Club, which will feature a dish inspired by the cuisine of the city under discussion.

Rosenfield showed that from its eighth century beginnings until the present Kyoto has struggled over its physical layout and its identity. Ironically, although known for its many Buddhist and Shinto holy places, Kyoto’s tenure as the capital of Japan began with an effort to break away from organized religion. Alarmed that the emperor’s daughter wanted to abdicate and give the throne over to a Buddhist monk, government officials decided to move the capital to Kyoto and severely limit the number of temples allowed within city limits.

The city was laid out on a strict, rational grid with major east-west and north-south thoroughfares dividing it into four quarters. Known as Heian-kyo, the capital of peace and tranquility, the site embodied principles of city planning imported from China.

“The layout suggests that the city is the seat of a benevolent ruler whose reign is in harmony with the forces of nature,” Rosenfield said.

Over the centuries, however, the city spilled out of its logical, symmetrical plan. The government complex was moved many times, as well as being redesigned in a variety of styles. In addition, a vast number of temples grew up around the city. Buddhist temples alone now number between 1,200 and 1,300.

Kyoto’s dual identity as both a political and spiritual center resulted in its accumulating an enormous number of spectacular buildings and artworks, of which Rosenfield was able to discuss only a tiny fraction.

These included the 11th century Byodo-in containing one of Japan’s most famous statues of the Buddha, the Hall of the 33 Bays with its army of many-armed deities, the 17th century Nijo castle featuring an assembly room decorated with murals of pine trees on gold leaf, as well as an assortment of Zen gardens replete with artfully placed rocks, tranquil ponds, and gravel meticulously raked into elaborate patterns.

He also showed many photos of old neighborhood Kyoto, an urban fabric marked by delicate carpentry, picket fences, tile roofs, and tiny, carefully tended garden plots. It was also characterized by proud craft traditions, neighborhood organizations, and local rituals, which Rosenfield remembered from his three-year stay in the city during the 1960s.

Today, many of these traditional crafts and patterns of urban life are being eliminated as a result of modernization. Indeed, this process has been going on since the mid-19th century when the West forced Japan to open its ports to foreign trade. Rosenfield emphasized the psychic turmoil this rapid process of modernization has caused and continues to cause for many Japanese, quoting the words of Kakuzo Okakura, a Japanese intellectual who served as consultant to the Asiatic Department of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and was a great friend of Isabella Stewart Gardner.

“We have bowed to their armaments, we have surrendered to their merchandise, why not be vanquished by their so-called culture?” Okakura wrote in 1903.

Rosenfield compared the resentment that many Japanese felt toward the West at that time to the rage expressed by today’s Muslim fundamentalists.

But these anti-Western feelings were matched by other trends that welcomed and embraced modernity, and over time a balance between the two forces was reached. In fact, Rosenfield said, “Japan has preserved its culture better than any other developing country.”

Today, Kyoto and the other cities of Japan face the same challenge that the rest of the world faces, Rosenfield concluded – building a humane and aesthetically enriching culture within the high-tech, commercialized civilization that is evolving throughout the developed world.

“Considering Japan’s successes in the past,” he said, “the chances are high that it will succeed in the future.”

Future lectures in the “Cities” series are as follows: Nov. 20, “Constantinople,” by Ioli Kalavrezou, the Dumbarton Oaks Professor of Byzantine Art; Jan. 29, “Athens,” by David Mitten, the James Loeb Professor of Classical Art and Archaeology; Feb. 12, “Delft,” by Ivan Gaskell, the Margaret S. Winthrop Curator, Department of Painting, Sculpture, and Decorative Arts; March 19, “Venice,” by Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., distinguished fellow and consultative curator of American art; and April 30, “Agra,” by Stuart Cary Welch, curator of Islamic and later Indian art emeritus.

For information about tickets, please call (617) 495-4544.