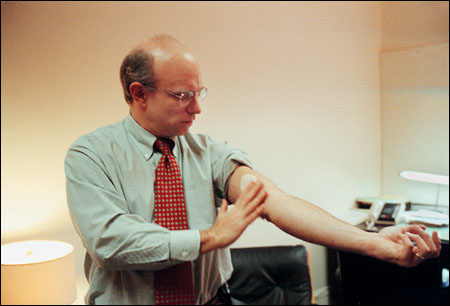

Bodkin is patching up depression

Imagine easing the blues of people who suffer from depression, the most common mental illness in the world, with a simple skin patch. Alexander Bodkin, a Harvard psychiatrist, did. Now, after years of setbacks, he and his colleagues have successfully tested an antidepressant patch that works without the side effects of the most popular pill forms, which include headaches, nausea, and loss of sexual appetite.

Almost half of the people who wore the patch recovered after only six weeks, and many of them “showed remarkable improvement much sooner,” according to Bodkin. “The patch worked, and worked rapidly without toxic side effects. The potential is very exciting.”

Bodkin and his colleagues, working at six medical centers, completed the first tests of the patch in 1998 (see Dec. 10, 1998, Gazette). The centers included Harvard-affiliated McLean Hospital in Belmont, where Bodkin did his research. These tests involved 177 people; 89 of them wore patches with an antidepression drug and 87 wore placebo patches with no drug.

Six weeks later, 42 percent of those who wore the active patch (37 people), no longer felt the pangs of depression. The patients continued to wear their patches for three months after their symptoms disappeared.

“Some of these people couldn’t even remember how it felt to be depressed,” Bodkin comments. “It could be the best treatment for about 20 percent of patients with depression, an illness that strikes an estimated 10 percent of people each year in the U.S. alone, and is one of the leading causes of disability in the world.”

The 1998 study has been repeated several times with varying results, “some of them very encouraging,” Bodkin notes. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) could decide on making the patch available to the public as soon as next year.

Delightful remission

The drug used in the patch, selegilene, is already available in pill form under the name Eldepryl. The skin patch may work much faster than the pill because the drug goes directly into the bloodstream instead of through the digestive system and liver first, according to Bodkin.

Known as a monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitor, selegiline is thought to interfere with the action of a protein that incapacitates brain chemicals, a shortage of which apparently underlies depression. Unlike Prozac-type drugs, selegiline does not cause side effects such as headaches, anxiety, apathy, nausea, and loss of sexual drive, the researchers say.

“Prozac-like drugs relieve distress but usually do not make a person feel good,’ Bodkin points out. Selegiline and other MAO inhibitors sometimes leave patients feeling well for the first time, a condition known as “remission with delight.”

The generation of joy by MAO inhibitors was discovered accidentally in 1952 by David Bosworth, an orthopedic surgeon who was trying to find a drug to relieve the bone and joint pain suffered by tuberculosis patients. Along with relief from the pain, Bosworth noted that his patients enjoyed feelings of elation and vitality. Selegiline itself caught the world’s attention in the 1970s when experiments with animals led to false hopes that it would prolong life, memory, and sexual activity.

However, selegiline and other MAO inhibitors fell into disuse when researchers found that they interfere with the digestion of a harmful byproduct in foods and drinks like cheese, soy sauce, wine, and beer. In some cases, the result can cause bouts of high blood pressure and even strokes. The FDA eventually approved use of MAO inhibitors with dietary restrictions, particularly for people who fail to benefit from other antidepressants.

The patch, Bodkin points out, bypasses the diet problem completely because the drug goes directly into the blood. During the 1998 study, the FDA insisted that participants adhere to special diets, but the agency dropped this requirement in more recently completed trials.

To get its approval, the FDA wants a new drug to produce improvement in all people who take it. “That neglects the important fact that there are different subtypes of depression,” Bodkin argues. “MAO inhibitors won’t work for all subtypes; neither will Prozac-type drugs. Only about 20 percent of patients enjoy remission with MAO inhibitors. But these are people not helped by other drugs, and they number in the millions in this country alone. For that reason, I think that the patch will ultimately be approved.”

Bodkin and his colleagues report results of the 1998 tests in the November 2002 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry. Results of later trials have yet to be published.