Allston:

A tale of two (potential) campuses

Planning for Harvard’s future development in Allston is picking up intensity as consultants and University officials push to complete their work by June, clearing the way for President Lawrence H. Summers and the Harvard Corporation to set a course for the development, possibly by this summer.

“We’ll have done enough groundwork to back up a decision,” said Kathy Spiegelman, associate vice president for planning and real estate, who was recently appointed chief University planner and director of the Allston Initiative. She takes over the new position Jan. 1, 2003.

The creation of the Allston Initiative and Spiegelman’s appointment as director were just the latest steps in Harvard’s preparations to transform the land it owns in Allston into a new, state-of-the art campus.

Consultants and University officials examining the question are meeting regularly. Headed by the University Physical Planning Committee, faculty and administrators are working in advisory groups examining the potential of any Allston development for science, housing, culture, and graduate schools. The Allston Executive Committee, made up of top administrators and faculty involved in the planning process, is meeting weekly.

In the course of their work, the planners are comparing and contrasting three scenarios: a professional school campus, a science campus and the use of the land for cultural activities and developing housing. The University Physical Planning Committee, which includes faculty members from throughout the University, has expressed a preference for a campus with an academic focus. The chair of the committee, Dennis F. Thompson, Alfred North Whitehead Professor of Political Philosophy and senior advisor to the president, says that academic needs and priorities will drive the planning for Allston. But he adds that student and community housing and cultural facilities will definitely be a central part of any Allston campus.

Including housing in its plans for Allston is just one way in which the University is heeding the desires of the Allston community. Concerned about competition from Harvard students for scarce housing, Allston residents have long expressed the opinion that Harvard should house more of its students on campus.

Consulting with the community has been a key part of the process from the start, according to Kevin McCluskey, Harvard’s director of community relations in Boston. Making that consultation a bit easier is the fact that Allston residents have begun a parallel planning process through which they are seeking to set a direction for the entire neighborhood for the years to come.

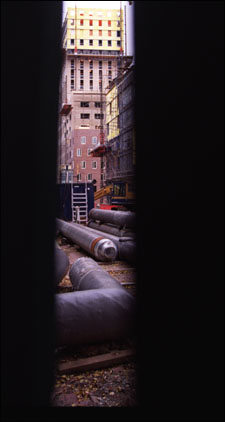

That process, like Harvard’s, is still under way, but seeks to build from the opportunities presented by Harvard’s planned transformation of former industrial land into an academic precinct.

“What we emphasize in the planning process is we’re working with a strong neighborhood to begin with. As the community’s vision meshes with Harvard, we anticipate a very positive result,” McCluskey said. “These are great complementary processes.”

Elbow room

The three scenarios each have their own strengths, according to University officials involved in the process.

A science campus would bring a variety of different scientists from different disciplines together in brand-new facilities, Thompson said. It could house researchers and faculty from the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard Medical School, and the Harvard School of Public Health. That would allow a greater degree of collaboration among disciplines and would provide expansion room for fast-growing fields.

A professional school campus would ease a space squeeze for at least two schools the Graduate School of Education and the School of Public Health that are feeling cramped in their current facilities, according to Thompson. It would also put disciplines that are collaborating more and more, such as education and government, near each other and allow them to construct new facilities from scratch that reflect their current needs and future plans, Thompson said.

“We could put almost all the professional schools there with the capacity to grow 50 percent in the future and have significant green space,” Thompson said.

Use of the land for culture and housing facilities rather than academic buildings is still on the table as well. Such a plan would bring cultural institutions such as Harvard’s museums together with student housing. That alternative would provide room to grow and improved access to the museums, one of Harvard’s most public faces.

The new development will not only provide new facilities across the river, it will free up more space for the faculties in Cambridge, Thompson said.

Thompson said unlike a business that discards old technology as new becomes available, a university accumulates knowledge, with cutting edge sciences demanding space along with philosophy departments which are doing new thinking about age-old questions.

“Healthy universities grow,” Thompson said. “Harvard has grown an average of 1 million square feet per decade . Even with the current plans of the schools, we are on a collision course in Cambridge. As we look further ahead, we have to prepare for continued growth of the University as a whole, even if not all of its parts will grow.”

No dumping ground

The Allston community is examining Harvard’s plans somewhat warily, but is also viewing them with an eye toward the potential they offer.

One concern the community has already voiced is that the area not be used as something of an academic “dumping ground,” filled with a hodgepodge of buildings and support functions that spill over from Cambridge. Harvard planners reflect that concern and each of the three alternatives would make significant new use of the Western Avenue corridor.

Paul Berkeley, president of the Allston Civic Association, expressed a bit of impatience at the length of the planning process, saying Harvard appears to be moving at a pace fitting with its 366-year history while community planners are anxious to finish the project in a shorter time frame.

Despite that, Berkeley said the planning process is positive because the University seems genuinely interested in the community’s concerns as it draws up its own plans.

“That’s kind of unique because usually a community just reacts to a university,” Berkeley said.

Berkeley gave the process high marks so far, saying Harvard may be having more difficulty convincing audiences inside the University of the wisdom of its plans than it is having with the Allston community.

“I think we have common goals,” Berkeley said.

Thompson agreed, “We are finding that there is more agreement between Harvard and Allston than within Harvard.”

‘Place-making’

Though the details of who will move to Allston and when are still being decided, Harris Band, director of physical planning for Harvard Planning and Real Estate, said many of what he termed “place-making” factors are shared between Harvard and the community. These elements will help determine what the new campus looks and feels like, regardless of who is working behind the buildings’ walls.

Both Harvard and the community share a vision of Western Avenue as an urban boulevard, rather than the industrial thoroughfare it is now. That means a more pedestrian-friendly street, with activity along its broad sidewalks. There is a shared vision for what is called Barry’s Corner the intersection of North Harvard Street and Western Avenue as a pedestrian-friendly urban center, vibrant and interesting, though not simply a clone of nearby Harvard Square, Band said.

Both the community and the University want to enhance pedestrian access to a major local resource, the Charles River waterfront south of Western Avenue, which is currently cut off by Soldiers Field Road.

Together with the development, Band said, will be some kind of commuter transit solution, such as a more convenient off ramp from the Massachusetts Turnpike, a commuter rail stop, or perhaps express bus service. Transportation between Allston and Harvard Square is also an issue and many possibilities are being examined, from a dedicated shuttle lane to light rail between the two areas.

Though details of these visions too must be worked out, Band said the sharing of these ideas between the community and Harvard has greatly eased the planning process. Together, they provide a framework for a livable campus and an attractive residential neighborhood that the greater Allston planners can build upon in drafting plans for the rest of their community.

“That’s the place-making piece of this. A whole range of community development options are unlocked with Harvard’s campus planning,” Band said. “I’ve been involved in community planning processes for many projects, but this one has been remarkable in its constructive and collaborative tone.”

Even with cooperation between Harvard and the Allston community, it is unlikely that ground will be broken very soon. Spiegelman said a likely time line would have groundbreaking in five years, with a 10-year target for relocation of major academic functions. It may be as long as 20 years, however, for a new campus to be in place.

“Fully mature campuses are not just dropped out of the sky,” Spiegelman said.