Patinkin counsels passion and patience:

‘First, follow your heart, but, second, you’ve got to use your brains.’

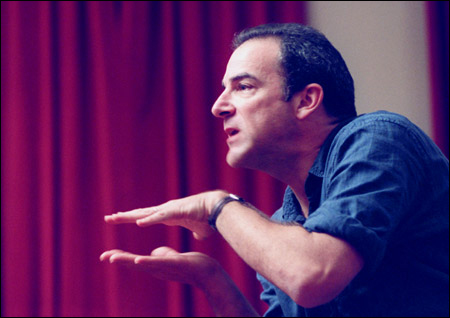

“I’m pretty fragile as a human being,” Mandy Patinkin told a group of undergraduates who had come to hear him speak last Friday (Sept. 27) as part of the Office for the Arts’ Learning From Performers Series. “It’s ironic because I often play parts that are rather big – tough, strong. I do that to make believe.”

Counseling other sensitive souls on surviving the rough terrain of show business was the theme of Patinkin’s informal talk at Winthrop House, the initial event of a two-day visit. He also managed to keep his audience entertained with spontaneous performances of Stephen Sondheim songs and stories about colleagues like William Hurt, David E. Kelley, and André the Giant.

Patinkin first attracted attention in the 1980 Broadway production of “Evita” and has since appeared in movies, television, and on the concert stage. He grew up in Chicago, dyslexic and learning disabled, with no particular interest in theater until a fellow student persuaded him to try out for a play at a local youth center.

A minor role in Cole Porter’s “Anything Goes” led to others, and he soon discovered a passion for performing. His interest continued at the University of Kansas, where he spent far more time in the theater than he did in classes and was finally counseled to leave the school because of his poor academic record. Deciding to seek professional training, he enrolled in the Julliard School of Drama in New York.

Patinkin was less than positive about this experience, which he found for the most part frustrating and discouraging. He accused the school of wrongfully dismissing gifted students and thereby snuffing out promising careers.

“Some teachers should be put in prison for the way they either take advantage of women in their classes or destroy fragile egos. Be careful who you ask to help you when you’re in the arts,” he warned.

Patinkin later elaborated on this cautionary topic when a student asked him what advice he would give to young performers.

“First, follow your heart, but, second, you’ve got to use your brains. Ask yourself, do I have it in me to have the shit knocked out of me, be turned down, fired and replaced, not work for seven or eight months and have to pack groceries? If you’re not sure you have it, then you’ve got to find ways of strengthening yourself.”

He quoted a therapist who urged him that he had better become as sane as he possibly could, “because there are more people who are certifiable in this business than in any other. People who go into the arts are often hurt people,” Patinkin said. “Many are manic-depressive. Some have tried suicide and some have succeeded. It’s just part of the game. We are people who are oversensitive. That’s why we’re in this business, because of our need to communicate.”

Not everything Patinkin said was in this admonitory mode. He also spoke of the joys of collaborating with kindred artistic spirits, like his piano player Paul Ford, who sat in the audience a stage whisper away and frequently reminded Patinkin of song lyrics that he was unable to remember. After years of working together, they now seem almost to read each other’s minds.

“The way we have learned to listen to each other, it’s eerie sometimes.”

He also spoke about his debt to composer Stephen Sondheim, of whose work Patinkin is a notable interpreter. His new CD, “Patinkin Does Sondheim,” is due out this month.

Patinkin said that he felt a deep connection with Sondheim’s work, demonstrating that connection by breaking into song when a word or idea reminded him of a Sondheim lyric.

“This man has given me my life on stage,” he said.

Another treasured collaborator was writer/producer David E. Kelley who created Patinkin’s character Dr. Jeffrey Geiger on the TV series, “Chicago Hope.”

“He stopped writing for the show after a while, and the minute he stopped I felt that my voice went out the window.”

He said he felt sad when his association with the show ended, although he was glad to give up the grueling schedule that kept him away from his family.

Asked to elaborate on maintaining a balance between work and family, Patinkin answered, “There’s no good answer. You pay for everything. Keeping balance and trust in your relationship with your partner is a much greater job than learning to be an actor. I’m not going to get any rewards for being the best balancer of life and work. It’s unrewardable. I’m just going to do the best I can.”