‘Murder at Harvard’:

Medical College case riveted 19th century Boston

The disappearance of a prominent Bostonian. Dismembered body parts in the bowels of Harvard Medical College. A trial that pitted a Harvard professor deeply in debt against a grave-digging janitor.

Fact or fiction? History textbook or detective novel?

Both, said historian Simon Schama and filmmakers Eric Stange and Melissa Banta.

The three visited the Harvard Film Archive Wednesday (Sept. 25) to screen their new film, “Murder at Harvard,” scheduled to air on the Public Broadcasting Service’s “American Experience” series in 2003. The film and the book that inspired it, Schama’s 1991 “Dead Certainties: Unwarranted Speculations,” take an unorthodox route through historical storytelling, one that makes frequent visits to fiction, arriving at a truth that may be even more precise than the facts suggest.

In history, said Schama, “you have to feed both the imagination and reason.”

Just the facts?

With many unanswered questions and enduring mysteries, the 1849 murder of George Parkman is rich fodder for the imagination.

Parkman, a Boston Brahmin trained as a doctor but practicing as a landlord and moneylender, disappeared on Nov. 23, 1849. His body (or parts of it) was discovered a week later in the basement of the laboratory of John Webster, a chemist at Harvard Medical College who was indebted to Parkman.

At a trial that drew tens of thousands of spectators, Webster was convicted, largely on circumstantial evidence, and sentenced to hang in March of 1850.

Ephraim Littlefield, the janitor at the Medical College who discovered Parkman’s body by tunneling into Webster’s locked vault, presented the prosecution’s most compelling evidence. Yet some believed that Littlefield himself was guilty of killing Parkman and framing Webster, whom he resented, for the crime.

“Murder at Harvard” tells the story of Parkman’s murder with film noir-ish re-enactments and a lush visual design more common to feature films than television documentaries. Local actors Tim Sawyer and Stephen Benson portray Webster and Littlefield, respectively, and the filmmakers used familiar backdrops like Beacon Hill. They even gained unprecedented access to film in Harvard Yard, using Harvard Hall as a stand-in for the Medical College.

The search for truth in the past

While the Parkman murder provides a grisly narrative, “Murder at Harvard” is as much about history – how do we tell the truth about the past? – as it is about guilt and innocence.

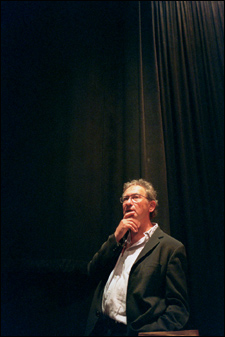

Schama, University Professor of history and art history at Columbia University who taught at Harvard from 1978 to 1993, appears on-screen as both narrator and commentator, describing how and why he chose to fictionalize Parkman’s murder in his controversial book “Dead Certainties.”

Telling the story from a variety of viewpoints – Webster’s, Littlefield’s, even Parkman’s – Schama illustrates how little we can really know about the facts of the past. So Schama filled in the holes left by the facts of the story with a tool borrowed from novelists: understanding the characters and their motivations.

Although respected for his work as a scientist, Schama learned, Webster lived beyond his means, throwing lavish parties at his Harvard Square home and ensuring his two daughters social debuts befitting their status. He borrowed from several lenders, including Parkman, who had come to Webster’s lab to collect a debt the day he disappeared.

While Parkman was a few rungs up the social ladder from Webster and certainly enjoyed more financial security, he had setbacks in his own medical career that may have made him envious of Webster’s scientific success, Schama said. When Parkman learned from his brother-in-law, Robert Gould Shaw, that Webster had promised to repay a debt to Shaw using property that he had mortgaged to Parkman, Parkman flew into a rage and threatened to take Webster to court.

Ephraim Littlefield, a “lowly janitor,” was not on the social radar of men like Webster and Parkman, but he did represent a growing tension between Boston’s elite and its poor, a tension mounting as Irish immigrants flooded the city. To augment his janitor’s salary, Littlefield was involved in the lucrative business of grave robbing, which at the time was the only way to provide the medical field with cadavers for research and teaching.

Schama, like the courts, absolves Littlefield of killing Parkman. Plumping the facts with fiction, “Murder at Harvard” presents Schama’s account: when Parkman comes to Webster’s laboratory to collect his debts and Webster stalls him, Parkman threatens the professor with taking him to court. Webster, panicked to imagine the impact a high-profile court trial would have on his family and his social standing, flies into a rage and kills Parkman by accident.

A tricky technique

In a question-and-answer session following the screening, co-producers Stange, currently a fellow at Harvard’s Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History, and Banta, a long-time curatorial associate at the Weissman Preservation Center of Harvard University Library, took the sold-out audience behind the scenes of their production.

Weaving the re-enacted story of Parkman’s murder with Schama’s commentary – as well as the commentary of historians and other academics – on the nature of truth-telling in fiction was the filmmakers’ biggest challenge, said Banta.

“It was an incredibly tricky thing for Eric and Melissa to combine these two narratives,” said Schama, who hosts the 16-part BBC series “A History of Britain.” “All sorts of people in high places were deeply skeptical of whether it would work. And so were we.”