Daddy longlegs have a global reach:

Daddy longlegs may prove to be valuable tools in the study of evolution, diversity, and environmental management

They’re quite a bit uglier than Darwin’s celebrated Galapagos Islands finches. Uglier than a canary in a coal mine too.

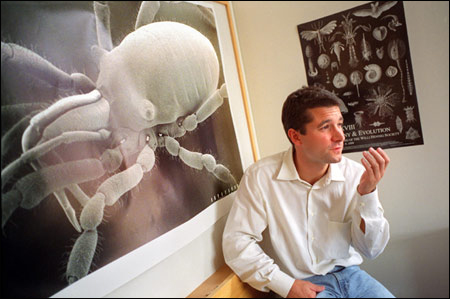

But Gonzalo Giribet’s daddy longlegs may serve the same function as both of those more attractive – to humans anyway – contenders. As a living example of radiant evolution and as an indicator that something is wrong in the forests where they’re found – or no longer found – the branch of the daddy longlegs, or Opiliones, family Giribet is studying may prove to be valuable tools in the study of evolution, diversity, and environmental management.

For now, though, Giribet, assistant professor of biology and assistant curator of invertebrates in the Museum of Comparative Zoology, is getting a handle on the sheer variety of these creatures. While most of the world’s large animals are known to science, huge numbers of arachnid and insect species remain unknown. Consequently, discovery of a new mammal, such as the Vu Quang ox in 1992 and the giant muntjack deer in 1993, both found in a remote area of Vietnam, were big news. But arachnologists like Giribet, toiling in relative obscurity, routinely identify new species – and their work is far from over.

Giribet has about 50 new species of daddy longlegs in his lab, some described, some in the process of being described. In addition, Giribet, an invertebrate biologist, has described five new species of mollusks, one species of terrestrial planarian – a type of worm often found in fresh water – and is working on the description of several new centipede species.

But Giribet said he’s truly excited about his daddy longlegs project. Over the next 10 years, Giribet hopes to identify most of the world’s species in the suborder of daddy longlegs that is his specialty, bearing the tongue-twisting name of Cyphophthalmi. He expects his work to double the number of known species, bringing the total to about 240.

Right now in his lab, Giribet has gathered specimens from museum collections around the world that he believes represent 50 to 80 new species.

There are also many new species out in the field, Giribet said. Four species were known to be native to the island of Sumatra until several recent trips found specimens belonging to 16 new species.

“There’s lots of hidden diversity out there we have to study,” Giribet said.

Describing a new species is a painstaking process, Giribet said, consisting of DNA sampling and comparing numerous physical characteristics, identified with the help of an electron microscope, with known species. Details such as a slight crest in the anal plate of a male specimen or the presence or absence of an anal pore, could make the difference in identifying the creature properly.

Daddy longlegs in the Cyphophthalmi suborder don’t closely resemble the daddy longlegs familiar to people living in New England. Though they’re in the same order, with the common name daddy longlegs, the familiar New England version is in a different suborder. Cyphophthalmi are much smaller, only between 1 and 6 millimeters long and, though they have a similar one-part body, have much shorter legs.

The Cyphophthalmi live in the leaf litter on the floor of humid temperate or tropical forests around the world. They eat mites and fungi. Their distribution indicates they arose long ago, as related species have been found in South America, Africa, Madagascar, Australia, and New Zealand, an area that was joined together 150 million years ago when all the Earth’s land masses were contained in two supercontinents. South America, Africa, Madagascar, Australia and New Zealand formed the southern supercontinent, called Gondwana. Another set of related species has been found in North America and Europe, which together with Asia formed Laurasia, the northern supercontinent, with a third set in the islands of Southeast Asia and a fourth in the tropics of West Africa and South America.

Giribet is interested in Cyphophthalmi because they are the only suborder of Opiliones that retains several primitive physical characteristics. That indicates Cyphophthalmi are likely the sister species to the others, he said, at the same time cautioning against thinking of them as the “ancestral” species.

“They have been diverging from the ancestor of Opiliones for the same time, so we talk about sister group relationships, not ancestor relationships,” Giribet said.

Study subjects?

There are two features of Cyphophthalmi that may make them valuable for scientists studying other topics. The creatures don’t stray far from home, Giribet said, giving rise to a great deal of endemism, or species found in only one location. On New Zealand, an island already famous for giving rise to new species, perhaps one-fifth of all currently known Cyphophthalmi – or more than 20 species -can be found. This feature – endemism (first identified by Charles Darwin in the profusion of specially adapted finches on the Galapagos Islands) can be valuable for scientists studying how evolutionary processes create new species.

“We’re always looking for examples like the Galapagos finches,” Giribet said.

Another feature of the Cyphophthalmi is that they are only found in forests relatively undisturbed by man. This may make them useful subjects for scientists studying environmental degradation and forest quality.

Collecting specimens can be quite challenging, Giribet said. Not only are the daddy longlegs small, they’re also camouflaged quite well to blend into the bits of dirt, leaves, branches and other litter that blankets the forest floor.

Cyphophthalmi are collected by putting leaf litter into canvas bags with a filter at the bottom. The stuff that comes through the filter is collected in plastic trays and examined by hand, sometimes for hours after the collecting trip.

“Sometimes you take the litter to the hotel and sift into the night,” Giribet said. “You always find less than you expect. You often don’t find them because the habitat has been degraded.”

Giribet and doctoral student Sara Boyer are planning a trip to New Zealand this winter to collect specimens of the Cyphophthalmi. Boyer said she’s never collected this species before, but expects to spend a significant amount of time in the forest, wet and dirty. When they’re not in the woods, Boyer said they’ll travel to New Zealand’s natural history museums and examine specimens there.

“We’ll construct family trees and look at how they’re related to species in Eastern Australia,” Boyer said. “We’re trying to put the evolutionary history of this group into the context of geological history of this region.”