Adoption enriches mosaic of Harvard life

“She is the reason my heart beats.”

Lynne Stack said it simply, while sitting in a Holyoke Center break room, as if the seven words about her daughter, Ming, say it all.

In a way they do, for Stack, a coordinator in the Harvard Trademark Program, and for many other adoptive parents scattered across Harvard’s campuses. But in another way, there’s much more to say.

The story of adoption at Harvard and elsewhere is a story packed with joys and sorrows, tough decisions and tough times, rewards, and love.

In sharing their experiences, Harvard’s adoptive parents describe the realization that they can’t have biological children, the sometimes-difficult decision to bring a child who started life elsewhere into their homes and hearts. They talk about interminable waiting, inscrutable paperwork, and well-meaning officials. They wrestle with the entanglements with birth parents, societal and family pressures, and the questions to be delicately answered.

The reward for it all, though, is the joy at seeing their child for the first time and holding him or her in their arms, watching the new family member grow up, and experiencing a new understanding of so many different parts of life.

“When you don’t have children, you can’t really imagine what it’s like, and once you do, you can’t imagine what it was like before,” said Lynne Farnum, the Sociology Department’s graduate coordinator, who adopted her son, Jae, from Korea five years ago.

While statistics are unavailable on the numbers of adoptive parents at Harvard, officials at the Office of Work and Family say the University is offering – and parents are taking advantage of – more programs aimed specifically at adoptive parents. Parents who adopted a decade ago remember little support from the University, while more recent parents cite financial aid, support groups, and a network of adoptive resources that have helped them along.

“I do think we’re in the forefront of supporting people who are adopting, both in our leave policies and in our other adoptive programs,” said Office of Work and Family co-manager Cyndie White.

Harvard currently offers paid and unpaid leave for new adoptive parents. In addition, the University offers grants of up to $5,000 to help defray the costs of adoption – a major benefit when costs can run three to four times that.

“That is immediately helpful,” said Tim Strawn, a geospatial resources cataloger with the Harvard College Library. Strawn and his wife, Pam, a professor of classics at Boston University, adopted their 5-year-old daughter, Reva, from India in July 2001. “I’ve been really impressed with the employee benefits and services.”

Besides such material support, the Office of Work and Family offers an informal parent-to-parent resource network so those considering adoption can talk to adoptive parents, and a series of monthly brown-bag lectures on topics specifically related to adoption. This fall’s lectures include topics such as adoption and school issues, dealing with infertility, and blending families of birth and adopted children.

“I try to balance programs so they provide something for pre-adoptive folks and for those who already have a child in the house,” White said. “All parents need to know that the challenges they’re facing are faced by other parents, that they’re not alone.”

The meaning of family

Several of Harvard’s adoptive parents said adoption is part of their family background and had been in the back of their minds as they thought about building a family.

Lynne Farnum’s older sister adopted her two children. Her husband, Steve Boylan, has a sister who was adopted from Korea at age 9. Steve also has two cousins who were adopted, and his adopted sister is now considering adopting a child from Korea after having three children by birth.

“It was a natural idea for us,” Farnum said.

But Farnum and her husband still sought to have children by birth. It was after three unsuccessful attempts at artificial insemination and one gamete intra-fallopian transfer – with the attendant medical intrusion into the most private part of their lives – that the final frustrating issue became Farnum’s age. At 42, she became ineligible for further treatment, she said. The anger and frustration she felt, though, gradually dissipated as she and Steve adjusted to their new reality.

“We both wanted the experience of pregnancy and birth,” Farnum said. “We both really wanted to – as archaic as it sounds – continue the family lines. We both have a strong feeling of family and wanted to feel we were passing onto our children something of our parents.”

Despite that initial desire, Farnum said they were thrilled when Jae came to live with them, and today she talks of trips to tae kwon do class and of Jae serving compost dinners to worms while she gardens nearby.

Farnum said she found Harvard’s adoption support groups helpful and that perhaps the greatest resource is the Harvard community’s accepting nature, its international flavor, and its openness to people, practices, and cultures that vary from the American mainstream.

Wait, hurry up, and wait some more

The actual adoption process depends on the route the prospective parents have chosen. Some people adopt family members’ children in a kinship adoption. Others adopt American children through private agencies, or through state child welfare organizations. Still others choose the international route, adopting foreign-born children, usually aided by an agency experienced in working with that particular country.

They’re all nerve-wracking.

Tim Strawn and his wife, Pam, chose international adoption and, with a shared interest in South Asian culture, decided on adopting a child from India.

They knew the process would be difficult, and at times it was.

The agency they worked with conducted a “home study” in September 1999, a step required of all families before adoption. The home study examines not just the parents’ physical home, but also their personal background and readiness to parent.

Once their home study was approved, the Strawns were put on a list and the waiting began. By March 2000, they had moved up to 12th. In June, nine months after the home study, they were called with what is termed an “assignment.”

A child had been identified for them.

Reva’s dark eyes and dazzling smile leapt out of the picture at them. Along with the picture were reports on her social and physical progress and bits of her story: She had been in an orphanage for about a year. Among the documents were medical reports on what doctors there had identified as epilepsy.

“When we saw her pictures we were sure we wanted to adopt her,” Strawn said. “We knew that even if we had a biological child there would be challenges we hadn’t even thought of that we’d have to face.”

They brought electroencephalograms and CT scans that had been sent with other documents to specialists at the Floating Hospital for Children in Boston. Doctors there disagreed with the Indian doctors’ diagnosis. The Floating Hospital doctors thought what Reva had were febrile seizures, which can be caused by illness and malnutrition. At least physically, they told the Strawns, everything would likely be all right.

Tim and his wife gave the adoption a green light and set about creating a “life book” to send her, with photos of her new home and family. And they dealt with a new round of paperwork.

“It seemed like there were so many hurdles to jump – the INS, tax records, birth certificates,” Strawn said.

The court process in India also took many months, and the delays were at times discouraging. Finally, in July 2001 they traveled to India to meet Reva and take her home. The waiting, Strawn said, was well worth it.

He and Pam were impressed with the warmth, selflessness, and good-humor of Reva’s caretakers. And Reva became a joy to them from the start, deciding on the first night of their three-day stay to come back to their hotel with them. The farewell ceremony, where other children in the orphanage sang songs to say goodbye, was deeply touching, Strawn said.

Today, Reva is in perfect health and, when she’s not swimming at the Malkin Athletic Center pool with her dad or delighting her mom, she’s chattering away with her new friends in kindergarten. In fact, Strawn said, it was seeing Reva interact with other children when she was in preschool last year that prompted them to seek another child from India. They’ve already received their assignment for Akshay, 2, and expect to travel back to India in April or May of next year.

“Reva is an extraordinary person who each day lives into more and more of her amazing potential,” Strawn said.

Adaptation and upbringing

Because of the way they’re created, adoptive families often must deal with issues of belonging, parenting, and the meaning of family in a more direct way than many others.

Jack Humsey, who today is 9, was adopted from Texas as an infant by Caroline Kent, head of the Research Services Division at Widener Library, and her husband, David Humsey.

Kent was 42 when she and David decided it was time to have a family. The two, who are white, were open to transracial adoptions and willing to work through state social service or private agencies. Consequently, the process proceeded quickly. Nine months later, they brought Jack home.

Adoption – of Jack, who is African American, and later of a second child, Desiree, who is of mixed race – seems to have gotten everyone in the Kent/Humsey family thinking.

“We’ve explored the meaning of adoption in very different ways,” Kent said. “We now think of social issues in a very visceral way. We think about the meaning of family in ways that many people don’t if they have birth parents. We think about race in America. These are lessons anyone could stand to learn whether they have birth children or get them through adoption.”

Kent said that the mixed racial nature of her family puts issues surrounding race in America right in the open for all to see, whether they want to or not. She said she’s lost some African-American friends because they disapproved of her adopting an African-American child and Caucasian friends because of clumsy or thoughtless comments.

“It’s always an issue. It was an issue with our African-American friends, one or two of whom are no longer friends. They never said we shouldn’t do it, [but one said] she didn’t want the race thing right in her face,” Kent said. “It puts race on the table in front of you.”

Over the years, Kent has become an advocate for multicultural, multiracial families. She has done presentations on the subject, including speaking at a conference on open adoption, and she helps run a national listserv – an e-mail mailing list – on transracial adoption.

“I talk because it’s important for me,” Kent says. “I believe people are very poorly educated about adoption – all people.”

Kent has spent the past nine years watching Jack – whom David affectionately describes as their “first three children” – come to grips with being an adopted child.

“The first thing they realize is their mommy is not their ‘real’ mommy, that’s a horrible [realization],” Kent said.

And the children know it. Kent, a strong proponent of openness in adoption, said that after Sophia, Jack’s birth mother, first visited when he was 7 years old, he screamed all the way home from the airport when she left.

“I have two such nice mommies, why can’t I have them both at the same time?” he asked during the ride.

“They know something isn’t right,” Kent said. “Adoption doesn’t happen because something went right. Adoption happens because something went wrong.”

When he was much younger, Jack asked to crawl under Kent’s shirt, saying he could hear her heart and was a “baby in her tummy.” Six months later, he asked to do it again, but, Kent described, “He said, ‘Mommy, this time you be Sophia.’”

“It’s made me very aware of the losses he’s had,” Kent said. “Jack says to me ‘Adoption stinks – but it’s not that I don’t love you and Daddy.’”

Waiting for baby

Despite the trials and tribulations, the rewards are great and some families expand again and again through adoption.

One of the bunk beds in Ming’s room is empty. Lynne Stack walks in there every night, saying a prayer for the new life she hopes will come into hers, Ming’s, and Joe’s.

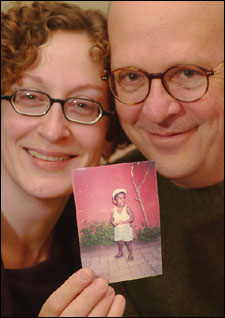

A world away, in the Maoming Social Welfare Institute in China’s Guangdong Province, is Jayden Mei Qin, a 15-month old, wearing a smile and a red dress with blue flowers in a photo sent to Stack in early October.

The Stacks expect to travel to China early in November and spend some time in Beijing. From there, it’s a flight to Guangzhou in the Guangdong province to pick up Jayden and attend a series of required governmental meetings. The last step is a visit to the U.S. consulate where they’ll get the final approvals and Jayden’s visa.

Then, hopefully by the end of the month, it’s back to the United States and home where the bunk beds await.

Stack reflected on Ming’s adoption more than five years ago and how the wait seemed interminable. With cultural and language differences, she was concerned about potential misunderstandings with Chinese officials. Once she held Ming, Stack said, they would have had to pry Ming from her.

“When she was placed in our arms, she took her little hand and wrapped it around our fingers. I just knew we were connected, we were meant to be,” Stack said. “I use the word ‘connection’ a lot, but that’s the way it felt. There’s no distance between us.”

Stack’s calmer this time, probably because she knows what to expect. Ming, though, is excited about having a baby sister.

“I think having Ming takes the burden off,” Stack said. “I am a lot more calm and patient, but I’m eager. I want that child in my arms.”